There’s a vignette that Senator Kamala Harris likes to tell about her mother, Shyamala Gopalan Harris. It’s a well-trodden soundbite that has proliferated into hashtags and official 2020 campaign merchandise, but the commercialization shouldn’t detract from its meaning: An immigrant from India who came to the United States with dreams of curing cancer, Shyamala raised Harris and her sister Maya to be strong Black women who are mindful of what their identities mean in American work and life. “My mother would look at me,” Harris has said, “and she’d say, ‘Kamala you may be the first to do many things, but make sure you are not the last.’”

Shyamala was right: Her daughter has been “the first” a number of times. In 2010, Harris became the first African-American and first woman to serve as California’s attorney general. In 2016, she became the first Indian-American woman to be elected to the United States Senate. In August of 2020, she became the first Black woman and first Asian-American woman to appear on the presidential ticket of a major political party.

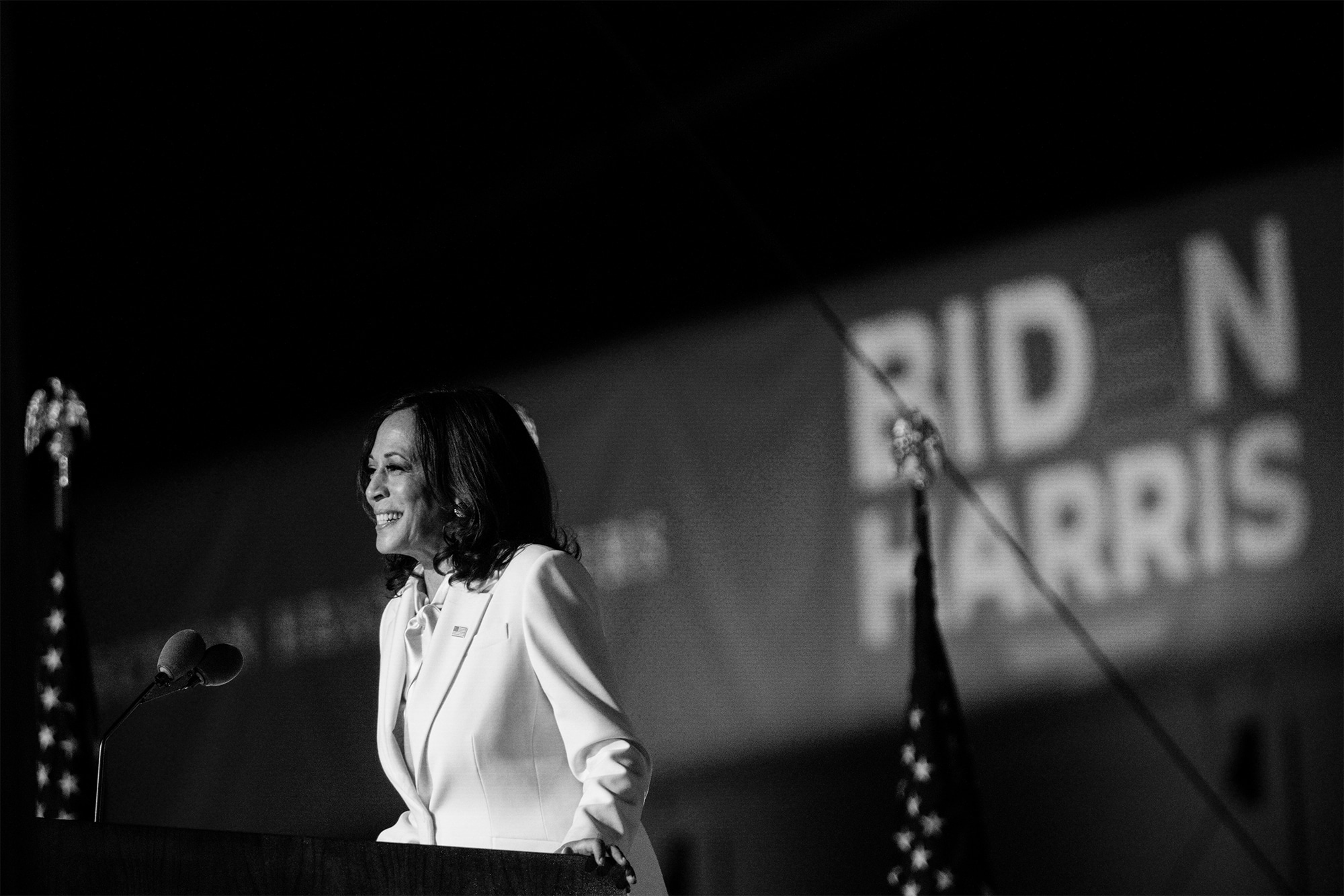

On Saturday, November 7, the Associated Press projected that former vice president Joe Biden and his running mate, Senator Kamala Harris, won the state of Pennsylvania and have earned more than 270 electoral votes in the 2020 presidential election. Senator Harris can therefore add more firsts to her list: she is officially the first female vice president-elect in United States history and the first person of color to earn the distinction as well.

In her first public statement after the race was called—a tweet—Harris didn’t mention these firsts. “This election is about so much more than @JoeBiden or me,” she said. “It’s about the soul of America and our willingness to fight for it. We have a lot of work ahead of us. Let’s get started.”

Harris’s presence in the 2020 race—both for as a candidate for president in the early days of the Democratic primary, and for vice president in the general election race—has been a potent reminder of what has been lacking in our nation’s highest office for more than two centuries.

Loading...

“It’s a kind of beautiful, full-circle moment for the story of America because I think women, and more specifically Black women, have done so much work—and are sort of the backbone of this country—without the acknowledgment of the work that we’ve done,” says Alia Daniels, co-founder of the global queer digital media network Revry. “And so I think being able to see someone who looks like me, in one of those positions, it’s just a level of pride that I don’t even know if I can fully express.”

Daniels notes that because we’ve seen women attain powerful positions in the private sector over the past few decades—consider former Pepsico CEO Indra Nooyi, or General Motors chief Mary Barra, to name a few boundary-breaking corporate leaders—it can be all too easy to take female leadership for granted. “But this is the highest position in our country that a woman has held,” she says. “There’s something to actually seeing it.”

The American public has already witnessed Harris asserting her expertise and authority on the national stage: her use of “I’m speaking” during the vice presidential debate last month was a master class in dealing with a male interrupter, and her questioning of then-U.S. attorney general Jeff Sessions and now-Justice Brett Kavanaugh in Senate hearings in 2017 and 2018 were similar showcases of feminine confidence and capability. But her impending presence in the executive branch of government has the potential to be as instructive as inspirational.

“No one can deny the power of seeing somebody who shares an identity, like your gender or your race, which are so salient in American society, certainly, in a position of power,” says Colleen Ammerman, director of the Gender Initiative at Harvard Business School. Ammerman points to research that has shown how female role models and mentors, as well as mere exposure to portraits of female leaders, can help encourage women to speak up, stand up and perhaps achieve more. “The images of leadership and power that we see are overwhelmingly white and male. Sometimes we don’t even quite notice that until we see something different,” she says.

Henah Parikh, development and communications manager at She’s the First, a nonpartisan nonprofit devoted to fighting gender inequality through education, puts it this way: “You can’t be what you can’t see.” She points to research that shows that, without female role models, girls stop believing they can be anything they want to be as early as 5 years old. Women like Harris help combat that.

“We talk a lot about these women trailblazers, like Kamala Harris who are the historic first, but they’re also paving the way for pulling other girls and women up with them,” Parikh says. “And that’s what’s so important to me and to a lot of women, but especially for me as a South Asian woman.”

Senator Harris’s election to the vice presidency comes at a moment when a pandemic has killed more than 200,000 Americans and forced thousands more out of work. Women have been disproportionately affected: According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 865,000 women dropped out of the labor force in September, compared to 216,000 men. The childcare and remote learning demands on mothers working from home stand to erase close to a decade of gains for women in the workplace unless spouses, employers and the government work to find solutions and provide support.

Harris alone cannot fix this. But for Aimee Koval, cofounder and president of Metis Consulting, a B-corp and certified disability-owned enterprise that provides technology and management consulting, Harris’s experience as a daughter, aunt and stepmother makes her more qualified than previous White House occupants to understand the unique challenges facing women.

“For me the big impact of choosing a woman in the White House is that that comes with a perspective that I think that we haven’t seen enough of, or enough understanding at a federal level from lawmakers who have not taken those concerns into account have not addressed issues such as childcare and the funding of schools,” Koval says.

Koval notes that fairly or unfairly, all eyes will be on Harris when it comes to these issues; this level of scrutiny and pressure is one of the well-documented downsides of being a “first” or “only” within an organization. In the federal government, where Democrats have held onto their majority in the House but control of the Senate is still unclear, women like Cori Bush—the first Black woman elected to Congress by Missouri—and the newly-reelected members of “The Squad” (Congresswomen Ayanna Pressley, Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ilhan Omar and Rashida Tlaib) can use their personal experiences and political sway to advocate for these policies, too. But the rates of women in government, even with a record 131 women so far elected to the 117th Congress, still lag that of the general public. The work is not over.

“I strongly believe that progress isn’t inevitable,” Harvard’s Ammerman says. “And I think it’s dangerous to sort of think, okay, we’ve broken one barrier and so we’ll just automatically keep going.”

Jackie Adams, coauthor of “A Blessing” and the first African-American female correspondent formally assigned to cover the Reagan and H.W. Bush White Houses for CBS News, has watched women vie for positions of power since Geraldine Ferraro was the first female vice presidential candidate on a major party ticket in 1984. Looking at the developments from the 2018 and 2020 election cycles, she finds reasons to be optimistic about female leadership beyond Harris’s fresh status as vice-president elect. “There are more women of color running for office than ever before,” she said. “I think that there is a flywheel that’s spinning and it might be pushed further ahead a little bit faster, [as] Senator Harris becomes vice president, but even if she doesn’t, it’s not gonna be stopped.”

The inspiration that Harris has already instilled in young girls is evident in the tweets and photos depicting Halloween costumes (Converse and all) and driveway stump speeches. But the significance of her election is not limited to the Gen-Z set.

“Senator Harris actually shares a birthday with my mom,” She’s the First’s Parikh says, going on to explain that both her mom and Shyamala Gopalan Harris come from South India, and both came to American with a lot to learn. Parikh describes hearing Harris talk so fondly about Shyamala and then texting her own mother.

“I said, ‘I just hope that you feel like you have seen some growth in this country, just by seeing this on television.’ Millions of Indian people around the country can relate,” she says. “It is something we’ve never ever experienced before.”

–By Maggie McGrath, Forbes Staff

Loading...