MUSTAFA SAEED SEES THE POTENTIAL OF ALL ART FORMS AS THERAPY IN A POST-WAR NATION, MOVING TOWARDS COLLABORATIVE EFFORTS TO MAKE THIS HAPPEN IN SOMALILAND, WITH A MARKETING AGENCY, AND AN INNOVATIVE HUB

HOW DO ARTISTS view work?

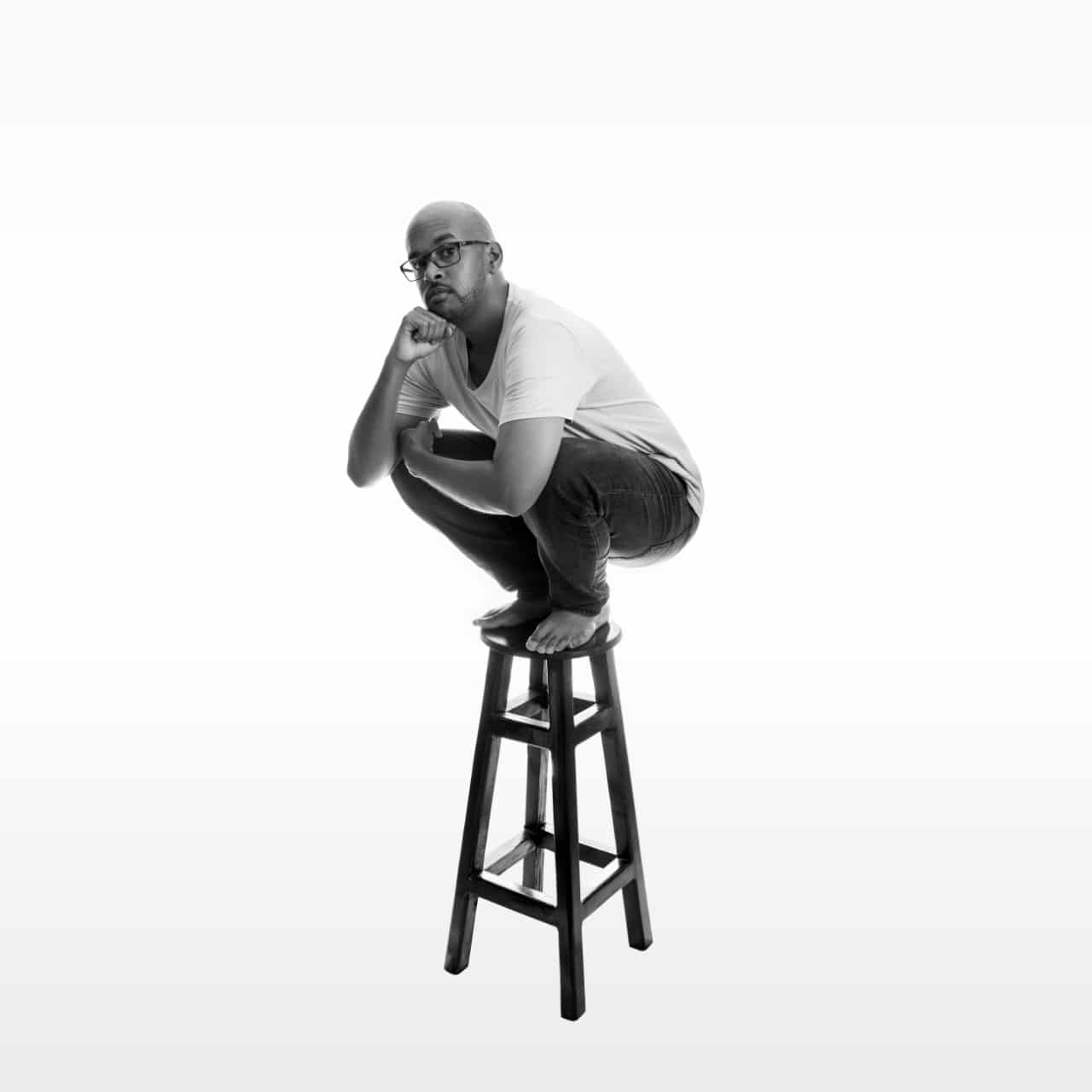

Take Mustafa Saeed, a self-taught Somali photographer and creative based in Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, for whom work is therapy.

For him, with the stress of a deadline comes euphoria, and his favorite aspect in combining different mediums to explore socio-political issues? The whole process itself – from pre-production to the camerawork, and post- production design.

Saeed grew up first in Saudi Arabia – where his parents met – watching the commercials his mother taped to VHS, and reading the free magazines that came with the newspapers his father bought. This was the first arty inspiration, marveling at the lay-outs of the publications and listening to catchy jingles. They returned to Somaliland when he was a teenager. Later, he went on to work in graphic design and advertising. Saeed became a photojournalist, doing documentary, NGO and commercial work.

Loading...

His favorite is conceptual photography, but he soon found there isn’t much demand for it – and the right infrastructure – in Somaliland.

“It’s not only the desire, we’re trying to create the demand. There’s no theaters, there’s no galleries, there’s no cinema, there is no fashion house, there is no stage to perform at. There’s private venues, but for anything creative to be on the forefront, the demand doesn’t exist,” says Saeed.

He says if interest develops and people hone their skills, maybe the demand will come.

“It will take time, but that’s the main goal, to create the demand. It will bring the accessibility and the more it’s demanded, there’s more opportunity and more solutions and all the options.”

Cornered Energies, a 2017 exhibition, happened when a creator approached Saeed about a video project named The Space of the Body.

“The minute I heard about the body and space, immediately it came to me; the lack of space for youth and creative spaces in this country, and how a lot of places are not so reachable. Life in the big city is very expensive, it’s very hard for people to sit in a coffee shop, go outside and gather in a space, find a job – the unemployment rate is very high. So it felt like these big minds and energies and soulful people, that can be useful and do good, and they’re being wasted. And nobody is seeing them.”

He tried to visualize the concept with the same social issues he was facing at the time, using photos, designs and snippets of interviews with local people to create the video.

He didn’t give them any guidelines, just a question about what it is like to be a young person in Somaliland.

Saeed’s work has been exhibited since 2012, in his hometown Hargeisa, Addis Ababa, as well as in Amsterdam, Johannesburg and the United States.

Last year, Saeed, along with four others, established a marketing agency, Muuqo, after working together on different ventures since 2016. Fankeenna, meaning ‘our arts’, is a youth-led platform, housing a studio, gallery and workspace for writers, painters, music-makers, believing that expression can create the social cohesion necessary to for an inclusive and peaceful society.

It is a fresh initiative, taking off in the last three months whilst they attempt to understand the environment they are in.

“We shouldn’t say this kind of medium or art doesn’t belong to us. It belongs to you the minute you make it Somali, the minute you make it with your own identity and inspiration. So that’s why we’re trying to introduce every kind of expression. I’m telling people, ‘do it as

if it’s your own, don’t limit yourself to say this might not meet up with our culture, it will meet up with our culture and environment when you claim it with your own identity’. That’s when the ownership comes in.”

Saeed says each issue has its own solutions. Creativity allows one to be open-minded and use critical thinking, and can be a tool for motivation.

“It’s always important, it’s always needed, it’s not an accessory, it’s not something on the side, secondary – it should always be forefront to everything we need to come through.”

He says the country has been through two different wars, with the trauma still present and connected to the younger generation.

“I think the media hasn’t been doing a lot of fresh things to grasp people’s attention, and give them the chance to heal, so I think art and art therapy is something needed in a post-war nation. And give people the opportunity to look at older issues in a different light.”

Since last summer, he has been recording the stories of children who try to migrate to Europe through Libya, facing a perilous journey. He met with the families, trying to translate it through pictures and text. A lot of these children come from poor family backgrounds, and when kidnapped, families cannot afford ransom except by selling their land. Some children are brought back with a program in conjunction with the Somali embassy and NGOs.

“I’m trying to see how these kids are getting back with a kind of heavy mentality, feeling the failure, and they try to integrate with society. Some people already lost trust with them, and they try to gain trust back. I’m trying to find what kind of lifestyle they have, what made them go, what’s their aspirations,” he says. The children face a lot of pressure from society, and navigating what they have left behind is difficult.

“I always give space for the person. I may come with my own camera, maybe with my own preconceived ideas, but at the same time, whoever I’m meeting, the people I’m photographing, I’m spending time with, I know their story, they know how they’re going to be seen, and how they want to be visualized. It’s a collaboration, it’s an energy and information we’re exchanging, but it’s always going to be what the person wants to share,” he explains.

In 2019, Muuqo snapped photos for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (UN), as well as a USAID funded project, and in 2020, was hired by the UN’s World Food Program, additionally for The New York Times to cover the 2020 marathon in Somaliland. In 2021, Muuqo photographed for the World Health Organization. The marketing agency has also done work on behalf of Somaliland’s Ministry of Fisheries.

Saeed also wants to go into NFTs (non-fungible tokens), and has an account on the Foundation, an exclusive invite-only platform.

“I want to come up with a special series that can be digital and grasp people’s attention. This is where the future is going – digital – and I’ve been doing a lot of digital conceptual artworks,” he says.

He hopes that somehow, someday, Somalian creative production will be accepted globally without compromising the artwork, and be seen for what it is.

Loading...