Following a dangerous suggestion by Donald Trump that household disinfectants could be ingested or injected to kill the coronavirus, Reckitt Benckiser, the maker of Lysol, immediately issued guidance on the matter.

“As a global leader in health and hygiene products, we must be clear that under no circumstance should our disinfectant products be administered into the human body (through injection, ingestion, or any other route),” the company said in a statement. “As with all products, our disinfectant and hygiene products should only be used as intended and in line with usage guidelines.”

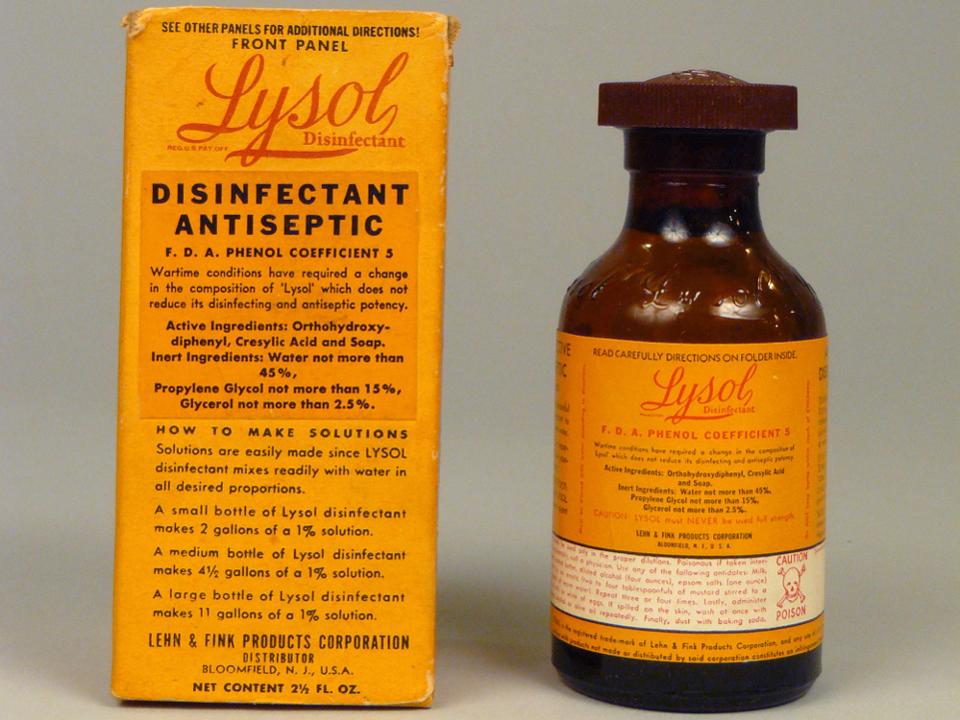

To be clear: Lysol is not medicine, and nor has it ever been safe to consume as if it were one. But what Lysol’s clarification in 2020 neglects to mention is that from the 1920s to the 1950s, the brand was telling a decidedly different story—that Lysol was a trusted “feminine hygiene” product, which, among other things, was a euphemism for contraception.

“She was a jewel of a wife… with just one flaw,” reads one ad from era. “She was guilty of the ‘ONE NEGLECT’ that mars many marriages. ‘LYSOL’ helps avoid this.” Admonishes another, this one with a “firsthand” account from a resuscitated union: “Our romance is so special again—now that I know about proper feminine hygiene care! Since I had that talk with the doctor, I use Lysol always for douching.”

That women’s private anatomy is inherently “unclean” is a misogynistic idea that is biblical in origin. But shaming women into pleasing their husbands isn’t the entire goal of these ads, either. As the author Andrea Tone notes in her 2002 book, “Devices and Desires: A History of Contraceptives in America,” douching was touted as an effective form of birth control (albeit more akin to the post-coital Plan B pill than the prophylactic daily pill) in the late 19th century and early 20th centuries. And thanks to the Comstock Act of 1873, which classified contraception as “obscene and illicit,” douching products could not be advertised as birth control. And so “feminine hygiene” became a euphemism, as did words like “germicide” (which has the handy feature of rhyming with the word it’s replacing).

Loading...

The implication of this dangerous marketing campaign? A wash of Lysol a day keeps the babies away. Except, not only did it fail to do this (a 1933 study of 507 women found that half who used douching as their contraception became pregnant anyway), but it was deadly. “By 1911, doctors had recorded 193 Lysol poisonings, including 21 suicides, 1 homicide and five deaths from uterine irrigation,” Tone writes in her book. A 1956 study that examined “Lysol-Induced Criminal Abortion” had similar results, finding “phenol poisoning” as a contributing cause of death to one of the patients in the study. Phenol was then, and still is now, an ingredient in Lysol.

ALAMY PHOTO AGENCY

Lysol, which at the time was manufactured by the firm Lehn & Fink, changed its formula in the early 1950s to eliminate cresol, one of its harsher ingredients that could cause burning, inflammation and death. By the 1960s, Lysol advertising shifted to focus on its utility as a bathroom disinfectant; meanwhile, birth control became legal for married couples in 1965 and unmarried people in 1972. Lysol’s use as a contraceptive would slowly fade, as would its reputation as such.

Lysol’s current maker, Reckitt Benckiser, did not immediately respond to a Forbes request for comment about Lysol’s days as an internal feminine hygiene product. Then again, even the president walked back his bizarre disinfectant recommendation during a task force meeting on Friday in the Oval Office. Trump claimed he was “asking a questions sarcastically to reporters just to see what would happen.”

But his message had already been heard loud and clear. As Hillary Clinton tweeted shortly before the president cleaned up his Lysol mess: “Please don’t poison yourself because Donald Trump thinks it would be a good idea.”

–Maggie McGrath, Forbes Staff, ForbesWomen

Loading...