SOUTH AFRICA’S NORTHERN CAPE PROVINCE seems to stretch endlessly, the largest in the country at almost 400,000sqkm. Relatively flat land gives way to farm after farm, with maize, sheep and cattle amongst thousands of plants and livestock under yield. Responsible for 12% of the country’s food production (StatsSA, 2020), the region has been increasingly struggling to deal with the impact of climate change, with dire consequences to food security projected in the future. Similar scenes are visible across the country’s major agricultural provinces of the Free State and Gauteng.

Mean annual temperatures in the region – and indeed across the country – have been increasing at 1.5 times the global average. Coupled with reductions in annual rainfall and shifts in seasonal rainfall patterns, the future of South African agriculture has many environmentalists and farmers concerned with how they will be able to put food on the country’s table.

While global awareness of climate change has accelerated dramatically since the early alarm bells of the 1970s, global action has yet to match the detrimental effects that human endeavors have wrought upon the world. Wealthy nations of the global north have strived – and often failed to meet climate agreements. The African continent, like much of the developing world, has reaped the least benefit of industrialization, but will likely bear some of the most damaging brunt of the effects of climate change.

Africa, and particularly southern Africa’s increased vulnerability to climate change, has been noted for several years, with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) stating in 2018: “New studies confirm that Africa is one of the most vulnerable continents to climate variability and change because of multiple stresses and low adaptive capacity… Some adaptation to current climate variability is taking place; however, this may be insufficient for future changes in climate.”

However, over time, the warnings are simply becoming more dire. The most recent IPCC report landed without much fanfare, arriving as it did four days after the Russian invasion of Ukraine. However, the conclusions the report painted could not be more urgent, with food security being one of the greatest challenges identified.

Loading...

“Maize-based systems, particularly in southern Africa, are among the most vulnerable to climate change… with yield losses for South Africa and Zimbabwe in excess of 30%.”

Professor of Climatology and lead author of the recent IPCC working group report, Professor Francois Engelbrecht, puts the situation bluntly to FORBES AFRICA: “Part of our job is to consider the worst-case scenarios. If we reach a global increase of 3oC, both the maize crop and the cattle industry in southern Africa are likely to collapse, due to the combined workings of more frequent droughts and heatwaves of unprecedented intensity and duration. This is the single-biggest risk for South Africa at the moment in terms of climate change, and in the next decade, this risk will keep on growing.”

Mouths to feed

The crux of the threat to southern African food security rests on several challenges; decreases in arable land due to climate change, reduction in or shifts in rainfall, radical population increases and extreme weather events.

The African continent’s population is amongst the fastest- expanding in the world, with the United Nations estimating that 1.68 billion persons will reside on the continent by 2030, the largest relative increase in population size in the world during that time period (UN, 2015).

Martin K van Ittersum et al (2016) in ‘Can sub-Saharan Africa feed itself?’ state: “Indeed, SSA (sub-Saharan Africa) is the region at greatest food security risk because by 2050 its population will increase 2.5-fold and demand for cereals approximately triple, whereas current levels of cereal consumption already depend on substantial imports. At issue is whether SSA can meet this vast increase in cereal demand without greater reliance on cereal imports or major expansion of agricultural area and associated biodiversity loss and greenhouse gas emissions.”

While South Africa is technically food secure at a national level – meaning that the level of food produced is technically sufficient to match the needs of its population – the distribution of resources is not equal, rendering some one in five households’ food insecure (StatsSA, 2017). How these households will be able to cope with rising costs and increasing population numbers is a major concern. South Africa’s own population growth is expected to reach between 65 and 67 million people by 2030 (UN, 2019), increasing the need for secure and resilient food production.

Resolution of food insecurity via reducing inequality is a mammoth task in its own right, with farming numbers illustrating that commercial farm numbers have remained static since around 2007, while yields due to technological innovation, which allowed commercial farms to increase income 288% from 2007 to 2017, but mixed and subsistence level farming overall had decreased, indicating that farms are increasingly being run and managed by large-scale organizations and consortiums (StatsSA, 2017).

Arable land reduction

On what land the farming of the future will be able to take place on is anybody’s guess. The World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF 2017) reports that only 12% of South Africa’s land is suitable for the production of rain- fed crops. With much more land available for grazing, it is no surprise that the largest agricultural sector in the country is livestock farming, making up some 80% of agricultural land use (Business Wire, 2020).

While that may seem like an effective application of available land, land requirements for food (or LRF) varies widely with application. LRF can be understood in simple terms as the bang-for-your-buck in terms of caloric production for a given amount of agricultural land, and livestock production and animal husbandry rank poorly on this scale in comparison to crop farming, and the land requirements for animal products being identified as one of the largest consumers of agricultural land, leaving the country at increased risk.

Corresponding to shrinking land availability of arable land is a decline in agricultural activity in subsistence and household agricultural activities overall. Commercial farm numbers seem to have remained steady over the last decade (StatsSA), but rural households have seen a massive abandonment of farming, with over half a million abandoning the activity from just 2011 to 2016 (StatsSA 2017). While these shifts are driven by a multitude of factors such as increased urbanization and variation in economic activities, it also represents a larger reliance on food imports and mass production for food security.

The cup runneth dry

“If you want a moment in time that is empirically defined, you can say that in 2002 we became a fundamentally water-constrained economy,” says Professor Anthony Turton, environmentalist and water scientist to FORBES AFRICA. “From that moment onwards, we were no longer able to mobilize the amount of water needed to maintain national food security and economic integrity.”

South Africa is classified as a water scarce nation, and its ongoing water security has been under threat for some time, challenging both urban and rural life. Drought, ailing water infrastructure and reduced or shifting seasonal rainfall have dovetailed to create a looming water crisis that threatens both the ability of farms to produce sufficient food as well as water to provide for normal functioning in urban centers.

Field crops such as maize, soya beans and wheat are the predominant products for ensuring food security, given that they allow a higher LRF than animal products. However, almost 80% of all field crops

are planted on non-irrigated lands, meaning that they are not irrigated, and that their yields are entirely dependent on rainfall conditions.

Trends identified in seasonal changes are critical to the agricultural sector, and have been identified as the wet season – where plants would ideally be sown – trending towards beginning later in the year and overall providing less rainfall than previous years, all of which negatively impacts crop yield. (The Conversation, 2020)

As Turton highlights, it is these areas that are most at risk. “These are the important phenomena that are unquestionably at play…” continues Turton. “… seasonal shifts in rainfall patterns… meant that areas that rely on spring rainfall for maize reduction were severely impacted.”

Both urban and agricultural industry and economic operation are fundamentally water-reliant, and scientists such as Turton and the Council of Scientific & Industrial Research (CSIR) took data from the National Water Resource working report from 2002 to model the future of South Africa’s water needs.

“What we tried to do then was we tried to project into the future as best we could, and we determined that by 2030 to 2035, we would need about 63 billion cubic waters per annum…” says Turton. “We can do one of two things really; we can get more water or we can use each unit of water more than once.”

Direct volume of rainfall in South Africa has been highly variable through much of the country’s history and is not seen as a particularly useful indicator in and of itself. However, overall rain days in the country have been decreasing, with an increased tendency toward region- specific droughts and extreme rainfall-related weather events, and it’s this that has caused the greatest challenges for the agriculture industry.

Namibia sits on the North-Western border of South Africa, and there is both geographical and agricultural overlap between the two regions, with farmers working similar crops on similar land. In 2019, Namibia experienced the worst drought in almost a century, with hundreds of thousands of livestock deaths and crop failures, the drought drove almost a third of the country without adequate food supplies (2019, Shikangalah).

South Africa’s Northern Cape province indeed followed suit in early 2020, officially being declared a disaster zone and almost $19 million being allocated by government for emergency drought relief. It was not enough to combat the multi-year effects of a drought that had been on-and-off in the province for almost eight years, primarily driven by the El Niño effect or warming of the Pacific Ocean waters. These massively damaging droughts had the expected impacts further down the supply chain.

Both food supply and prices suffered accordingly, with major spikes in the price index of maize immediately after droughts in 2016 and 2020. The impact on maize production was so severe that in 2015, South Africa began to import maize in large quantities for the first time (GrainSA, 2015), with almost nothing imported before 2013. The commercial and subsistence livestock sectors were similarly affected, with an overall decline estimated at 8.4% in commercial agricultural productivity (Lottering, 2020) and an average loss of subsistence farmers of between 29% and 43% of their herds (Vetter, Goodall, Alcock 2020).

Food price inflation increased correspondingly, with the largest increases coming after droughts in 2009 and 2016, surging to almost 15% (Trading Economics, 2022), which harshly affected both commercial food producers and consumers.

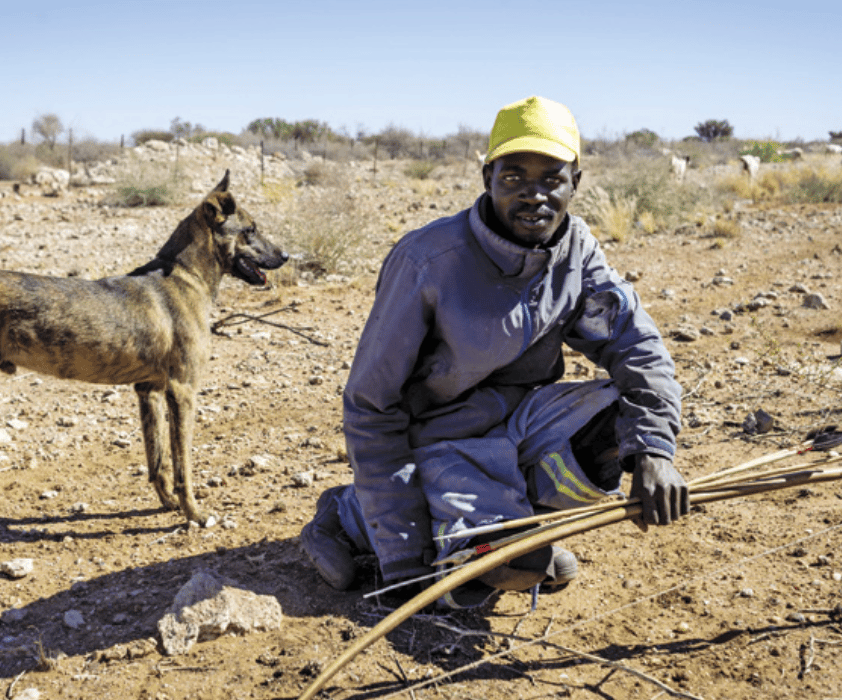

However, it is not just commercial enterprise that suffers the effects of drought. Almost 15% of all households in South Africa engage in some form of subsistence agricultural activity, producing fruits, vegetables and managing both livestock and poultry (StatsSA, 2017) – they too were not spared the impact of droughts.

“Our biggest problem as peasant farmers in this area over the years has been continuous dryness, heatwaves, and less rainfall. As you can see, we depend on rainfall in our farms. Our farm production depends on rainfall. Most of our crops wither, damaged (dry) due to severe sunshine or high temperature (humidity). We sometimes do not get anything from what we planted, absolutely nothing to harvest from these crops. We do not have irrigation facilities which we can use to get water from the river. Hunger is a common problem here. Because of drought in our community, farming is no longer attractive, especially to the youth,” said one 54-year-old farmer interviewed by researchers in 2021 (Novienyo, Laura & Simatele, Mulala, 2021) .

Urban centers are not invulnerable to the impact of droughts either, with the 2017 drought crippling the city of Cape Town, having suffered severely low rainfall for almost three years. With dam levels supplying the city dropping to between 15% and 30% of capacity, the city was forced to implement severe water restrictions and reduce overall consumption by over half.

Urban water security is almost equal in importance to ongoing food security as is agricultural food production, as the fundamental logistics and economic activities of the supply chain that provides the access component of food security is often urban centered.

One such example would be South Africa’s economic hub of Gauteng suffering a similar challenge to that of the Cape Town, experiencing its own ‘day zero’ drought.

“During the last major El Niño event, we had a four-year drought that ended in September of 2016. In Gauteng for example, [during that drought], the Vaal Dam, which supplies around 50% of Johannesburg’s water, dropped below 25%. If you speak to Rand Water, they’ll tell you that if the water level drops below 20%, for water quality and engineering reasons, the dam will no longer be able to supply water,” says Engelbrecht.

This would likely bring much of the economic activity within the province to a standstill, and would also mean that resources and logistics ordinarily geared toward normal business operations and even food transports would have to shift to focus on dealing with water challenges.

“A human being can survive on two liters of water a day – that’s all you need for a person’s life,” says Turton. “If you want to wash your clothes and produce food properly and garden then you need 200

liters of water per day,” he continues. “If you want to have a person on a healthy diet of 2,000 calories a day per person that goes to 2,000 liters, that’s an order of magnitude jump. This is where the invisible water, the water that enables the economy and the energy and food we produce and goods and services – known as virtual water, the economic enabler, that’s the critical thing.”

Supply chain and what we waste

Broadly summated as the process of how food ends up on the table, the food supply chain includes the production, processing, distribution, consumption and disposal. While the direct impacts being felt by climate change are primarily felt by the production and processing aspects of the chain, and the consumption most affected by population growth, aspects of processing and disposal are as crucial to the overall food security for the country.

And here, South Africa could increase its overall food security by an order of magnitude dealing with current challenges; research by the CSIR last year indicates that South Africa wastes the equivalent of 45% of the total available food supply in the country, a staggering 10 million tons of food annually.

The majority of the waste occurs at early stages of production and handling, with much of the remainder being due to processing and packaging, with the smallest amount of waste happening at the consumer level. Much of the wastage is due to perceptions around the desire of consumers – most middle-class consumers expect to see round tomatoes, vegetables that conform in size, and this challenge is further managed by packaging, whereby consistency in size and form of products is much simpler to transport, package and present for sale.

While these demands are sensical, the scale of the wastage is enormous, with some of the waste being diverted toward animal feed, but the vast majority ending up in landfills. In a country where almost 10 million people go hungry every week, this is tragic for the distribution and sustainability of the food security supply chain.

Major retailers have become signatories to the Consumer Goods Council of South Africa’s food loss and waste voluntary agreement, which aims to set compliance guidelines and training to reduce wastage at the retailer level, training staff on refrigeration best practices, surplus food donations and streamlining the overall food management process.

Food supply is heavily reliant on supply chain integrity, and South Africa has risks to both the efficiency of its supply chain and socio- political threats to the supply chain management.

Unrest in July of 2021 across the provinces of Gauteng and KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa led to widespread looting and obstruction of major supply routes such as the N3 highway, which led to food shortages across large areas in the country, with queues forming outside grocery stores for basic goods and many goods being spoiled as they were unable to be transported.

Similarly, fuel supply and prices affect food security for the majority of South African households, with year-on-year food inflation at 6.7%, outstripping headline inflation at 5.9% (StatsSA).

Resilience

While the frequency of subsistence farming provides a vector of risk to food security, it may too be its saving grace. With food expenditures approaching 40% in lower income households in South Africa (GrainSA, 2020), some researchers posit that increased subsistence farming can be a protective factor against general food insecurity.

Subsistence farming and smallholder agriculture have been shown to provide some degree of a protective effect against food price inflation specifically, which improves overall food security in these demographics. However, the way that this is occurring is in parallel and indeed in response to rising food prices, with the number of households engaging in agriculture declining but the number of households engaging in subsistence production to supplement their food purchases rising alongside it (Baiphethi & Jacobs, 2009).

Technology and historicity are both being applied to examine alternate sources of food for the future of the continent, with pioneering efforts in meat alternative and lab-grown meat supplies highlighted as possible protective factors against food insecurity in the future.

One such company profiled previously in FORBES AFRICA is Mzansi Meat Co, which is pioneering the creation of cultivated meat on the African continent, in line with global market efforts to provide ecologically sustainable meat-based proteins. Mzansi recently unveiled a taster of their first cultivated-beef patty at an event in Cape Town. The partial motivation for the founding of the company itself was to improve global food security and sustainability, says Co- Founder Brett Thompson to FORBES AFRICA.

“… looking to the rest of the continent, we’ve got a billion people coming in, who are going to be here in our lifetime, the next 20 years…” says Thompson. “How do we feed these people? We want to be a part of that.”

Initiatives at the policy level are also being examined, both in South Africa and on the continent, with the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries outlining a National Policy on Food and Nutrition Security working document in 2013, which identified the impact of climate change on food production, as well as disparities in food supply distribution and supply chain wastage. The document is largely in line with the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization’s recommendations at the time, however with no working documents released since then, government has not provided a policy update nor highlighted any clear efforts in state speeches.

Conclusion

The bell is being rung worldwide for climate change, but the ripple effects will be felt with great impact from the commercial farms of South Africa’s Free State province, to the subsistence farms in KwaZulu-Natal and the restricted taps of major economic hubs of Johannesburg, Cape Town and beyond. However, innovations in land use and food production do have the ability to moderate and even overcome the obstacles offered to food security in a world turned upside down by climate change.

The proof of this will be in the basics – as they say – “the meat and potatoes”.

Loading...