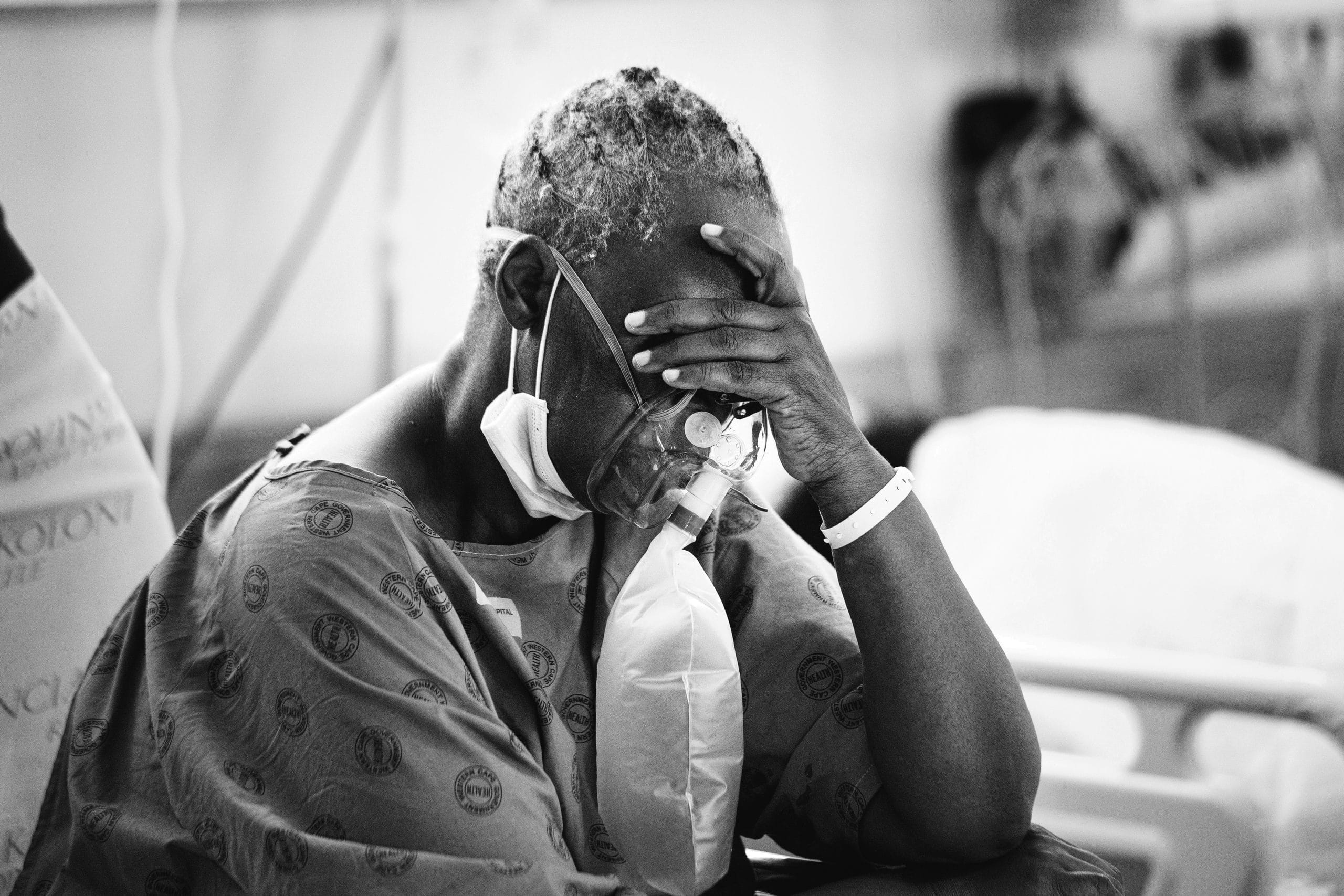

India literally choked for breath at the height of its catastrophic Covid-19 pandemic peak in April and May. Critical medical oxygen is usually the first resource to run low during respiratory emergencies. Currently in its third wave and with talk of an impending fourth wave, how is South Africa equipped to handle such a crisis?

On a bleak Sunday afternoon in late June in Johannesburg, South Africa, Dr Anne Biccard, while on a particularly arduous shift, watched three young people being rushed into the emergency department gasping for oxygen. They had Covid-19, and the hospital, already bursting at the seams with pandemic patients, had no available ventilators.

The immediate solution would have been to plug the new patients to oxygen concentrators, but unfortunately, the hospital could not find an extension cord to plug them into.

“On a Sunday afternoon, where do you think we were going to find one,” Biccard asks. “Silly things like that seem to be like insurmountable challenges.”

The hospital was left with no choice but to try something they had never done before.

Loading...

“We had to take the equipment from theater – the anesthetic equipment that we use to put patients under and use that to ventilate the patients in the casualty,” Biccard recounts to FORBES AFRICA.

In dealing with the third wave of the pandemic in South Africa, which Biccard says has been worse than the first (July 2020) and second waves (January 2021), hospitals have been overwhelmed and breathless themselves.

Biccard takes a break from the pandemonium in the emergency room to catch her own breath outside as we speak.

“In the first wave, we saw what was happening overseas and were much better prepared… It’s crazy out here! This is my life right now; all of our lives!”

The past few weeks, the Delta Variant, first detected in India in March this year, has catapulted South Africa as the continent’s Covid-19 hotspot, recording a total of over 2.3 million positive cases and 67,000 deaths at the time of going to press.

And with that, the clamour for oxygen for critically-ill patients who develop shortness of breath, one of the hallmark symptoms of Covid-19. India, at the height of the last wave reported the highest daily death toll of any country, and witnessed a severe oxygen shortage and crisis that sent the country into a tizzy looking for oxygen cylinders, ventilators and concentrators, in addition to life- saving drugs and hospital beds.

“We are running out of oxygen,” the Executive Director of Delhi’s Batra Hospital, Dr Sudhanshu Bankata, told NDTV on May 1. “We are surviving on oxygen cylinders, and in the next ten minutes that will run out. We are in crisis mode.”

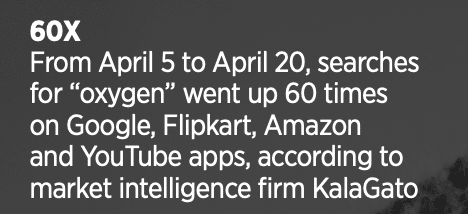

From April 5 to April 20, searches for “oxygen” went up 60 times on Google, Flipkart, Amazon and YouTube apps, according to market intelligence firm KalaGato, as reported on Quartz.

Furthermore, online searches for “oxygen concentrators” and “cylinders” in India went up over 400 times, also as per KalaGato.

“The Delta Variant alarmingly spread like wildfire in India, medical oxygen has been scarce,” South Africa’s President Cyril Ramaphosa said in his nationwide address on June 27.

With a predicted fourth wave of the pandemic in South Africa, what are the ways the country will cope in the face of such a crisis?

Professor Koleka Mlisana, Executive Manager: Academic Affairs, Research and Quality Assurance at the National Health Laboratory Service (NHLS) and also co-chair of the Ministerial Advisory Committee (MAC), thinks that as alarming as the state of affairs in India was, it may not be the same for South Africa.

“Are we going to get to the levels of India? I would hope not because firstly, we are just a smaller country,” Mlisana says in an interview with FORBES AFRICA.

Secondly, though there are challenges with numbers that would compromise resources in the country, Mlisana opines that even then, South Africa would still not have a problem.

However, the key lesson that came from India’s catastrophic Covid carnage was the shortage or lack of resources and Mlisana is certain that this will not be a concern for South Africa.

“As a country, yes, we have challenges,” Mlisana responds. “But if you’re looking at, for instance, oxygen supply, I think from the first and the second wave, the Department of Health was able to plan and make sure that they will have a constant supply of oxygen.”

Biccard, however, says that she is still worried about capacity issues when it comes to public and private healthcare in South Africa, especially in the third wave. Way before the third wave peaked, Biccard saw as many as 20 Covid-19 patients a day.

“And this is if they know they have Covid,” she explains. “And on the other side, you’ve got everybody else who’s coming to the casualty with other problems.”

We are also reliant on cylinders for the vast majority of patients requiring care and the logistics of getting enough cylinders to where they were needed in sufficient quantities proved an impossible task.

– Dr Craig Parker, Umoya

WHO’s Regional Director for Africa, Dr Matshidiso Moeti, said in a statement on July 1 that with the rampant spread of more contagious variants, the threat to Africa rises to a whole new level. “The speed and scale of Africa’s third wave are like nothing we’ve seen before. Cases are doubling every three weeks, compared to every four weeks at the start of the second wave,” Moeti said.

Can we take O2 for granted?

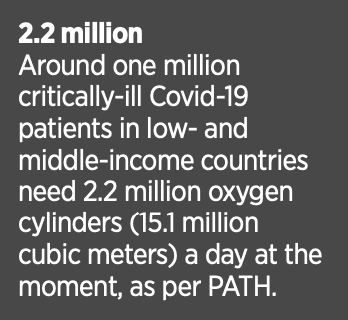

The Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI) reported this year that medical oxygen shortages around the world have been a tragic feature of the pandemic, impacting the poorest countries disproportionately. Additionally, a report released by PATH, a global team of innovators working to accelerate health equity, suggested that around one million critically-ill Covid-19 patients in low- and middle-income countries need 2.2 million oxygen cylinders (15.1 million cubic meters) a day at the moment. The concern should be mostly directed in Africa, Latin America, and Southeast Asia as there are surges reported.

“Oxygen access has been a long-neglected element of health system planning, despite being an essential treatment for a range of diseases. The Covid-19 pandemic has spotlighted the role of medical oxygen as a life-saving therapy for patients struggling to breathe,” the report stated.

The World Economic Forum (WEF) said in May that the new waves of the Covid-19 pandemic in countries such as Kenya and India “have shone a spotlight on the availability and accessibility” of oxygen.

Like PATH, WEF agrees that low- and middle-income countries face huge hurdles in getting this critical element to patients: “In many countries, proper systems to supply oxygen have been neglected for decades, despite pneumonia being the single biggest cause of hospital admission in low- and middle-income countries, even before the pandemic.”

This is proven in multiple reports in countries across Africa that have since the pandemic begun seeing shortages of oxygen.

In South Sudan in July last year, WHO and the UK’s Department for International Development had to hand over 160 oxygen concentrators to the country’s health ministry to support its response to the pandemic.

WHO stated in its release that oxygen, unfortunately, is usually the first resource to run low during a respiratory emergency as there was a severe shortage of medical oxygen in South Sudan, the youngest country in the world that just turned 10.

In August 2020, WHO also donated 21 oxygen concentrators to Liberia’s health ministry. Stats released by Liberia’s Service Availability and Readiness Assessment (SARA+) and Quality of Care (QoC) in 2018 had shown that only 58% of the hospitals had oxygen.

The Tennessee Tribune detailed at the end of June this year that medical oxygen has been scarce in Uganda. A May 2020 study released by British medical journal The Lancet found that Sierra Leone has only two functioning medical oxygen plants.

But even if there is supply, do people have access to them?

The key factor that came out of India’s experience was that people needing ventilators could not find them or get them. But Mlisana feels that for South Africa, this is not the case.

“There’s enough supply in the country, according to preparation plans, but the issue that often comes up is the replenishing of the cylinders, which is a major operational and logistical challenge.”

This then brings to the fore the logistics and business of oxygen supply.

“They did mention that sometimes we will say that there’s no oxygen, but it’s not because there’s ‘no oxygen in the country’,” Mlisana explains. “It might be somebody did not order when they were supposed to, so that probably definitely needs to be fixed.”

Furthermore, Mlisana states that the health department has made it clear that there are sufficient quantities of both non-invasive wells as invasive ventilators. This is specifically projected for the epidemiological modeling per province.

But given the reality that Covid-19 is unpredictable, what are the different creative innovations needed in this space should there be excess need?

Futurist Jack Ulrich talks about the consistent new innovations that need to come up.

“There needs to be continued solutions in addressing both Covid and all its variants that are coming,” he tells us, hinting that the virus is not going away anytime soon.

WEF says that planning in the context of the size of a hospital could help in coming up with solutions. For instance, a medium-sized district hospital (treating 15 to 20 patients with oxygen daily) will need upwards of 40,000 liters per day.

“To meet these needs, the provision of oxygen should be done using oxygen concentrators and oxygen generators, using some cylinders for immediate emergency use, such as transport in an ambulance.”

The most crucial and immediate solution, according to WEF, would be for governments and health services to invest in bedside oxygen concentrators and generators to supply whole hospital or district needs.

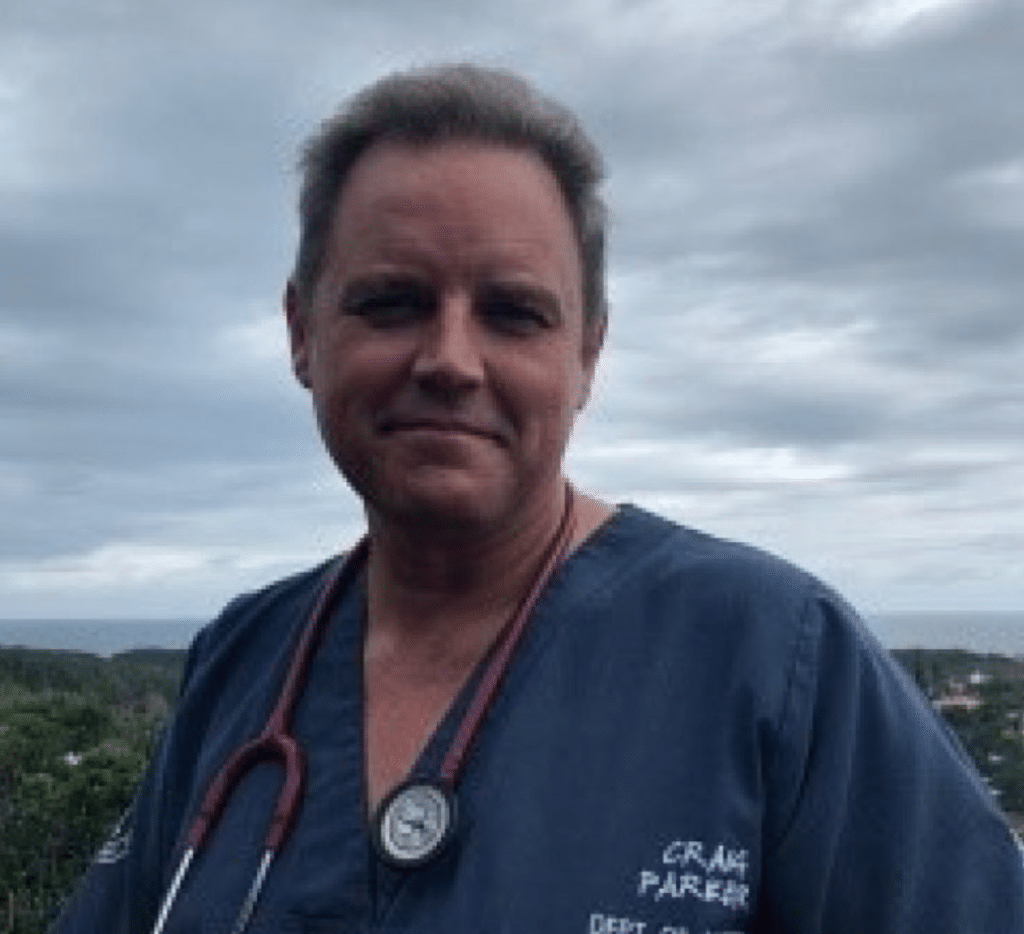

Dr Craig Parker is a lead doctor at Umoya in South Africa, a project launched during Covid-19 to design and test innovations that could

be critical to developing viable solutions during the pandemic. It is Parker’s opinion that now more than ever is the time for innovations to be tried and tested.

“Health has to become more inclusive and accessible to the vast majority of the earth’s population who are not wealthy,” he tells FORBES AFRICA. “We need a new way of doing medical supplies and equipment that make them affordable for public health programs.”

One of the innovations that have come to the forefront in Africa is mobile oxygen technology. FORBES AFRICA spoke to the founder and CEO of LifeBank, Temie Giwa-Tubosun, in Nigeria.

LifeBank is a supply chain company that uses data analytics and a tech-driven multimodal distribution platform to improve access to critical medical consumables for emerging markets. As per its recent stats, it has saved over 14,000 lives by delivering 42,000-plus medical products to 1,000-plus hospitals across Nigeria and Kenya.

The company also just launched an oxygen plant in the market center of Nigeria’s Nasarawa State.

“We impact vulnerable communities in urban, peri-urban, and rural Africa by delivering to the very last mile using the best mobility solution ranging from drones to motorcycles, powered by tech like data analytics as well as blockchain technology,” Giwa-Tubosun says.

Despite the skills shortage Africa faces, innovative companies like this are looking for solutions to preempt any foreseeable shortage of oxygen when the pandemic peaks again.

Umoya, for example, has invented a cost-efficient, easy-to-use oxygen device, OxERA (Oxygen-Efficient Respiratory Aid). The product, approved by the South African Health Products Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA), bridges the gap between current standard oxygen therapy via face masks and ICU-based non-invasive or mechanical ventilation while requiring no more oxygen flow than a standard face mask.

The inspiration for OxERA came when Parker envisioned the extent of the pandemic and also the huge problem developing countries would face with life-saving oxygen supplies.

Parker tells FORBES AFRICA that South Africa’s overall preparation was “not that bad” but could have been better in certain areas, like the oxygen supply sector. According to Parker, the oxygen supply infrastructure and an unhealthy reliance on so few suppliers means that South Africa may have been caught off guard by the magnitude of oxygen required during the peaks.

“We are also reliant on cylinders for the vast majority of patients requiring care and the logistics of getting enough cylinders to where they were needed in sufficient quantities proved an impossible task. We also focused our efforts on ventilators and high oxygen consuming devices which have proved to be very ineffective in areas where oxygen supply is constrained,” says Parker.

He designed OxERA to address this critical need. As a new class of devices, Umoya is trying to get formal trials completed as quickly as possible so that uptake can be increased with more trust.

Reiner Gabler, the Managing Director of Gabler Medical in Cape Town and Gauteng that manufactures and distributes the OxERA, says the volume of sales has been good and most sales have been to the private sector and NGOs supplying government hospitals, both in South Africa and the surrounding countries.

“The price of the device varies significantly depending on volumes and transport costs, but it can be said that the OxERA is well-priced compared with breathing circuits for ventilators, CPAPs (Continuous Positive Airway Pressure) and High Flow Nasal Oxygen therapy which are the alternative treatments for patients with low SATS levels and breathing difficulties,” says Gabler.

There are companies in South Africa also specializing in renting out medical devices like oxygen concentrators, operating on a 24-hour basis to ensure that those with desperate respiratory issues have access to them.

Breathe Easy Medical in Johannesburg tells FORBES AFRICA that in comparison with previous peaks of the pandemic in South Africa, they have seen an unbelievable increase in demand for their products during the current third wave.

“It has increased by at least three times resulting in us not having adequate supplies,” says Ronessa Govender from Breathe Easy.

“Everyone is breathless and all they want is for us to help them survive.”

Breathe Easy supplies oxygen to about 15 hospitals and rents out around 300 oxygen concentrators to desperate patients.

“Although we were prepared for this pandemic as well as the third wave, I would say the demand exceeded our expectations,” Govender admits.

Ecomed, also based in South Africa and specializing in rentals, notes how Covid-19 highlighted that critical medical oxygen is a “life-saving therapy for patients with low oxygen saturation”.

Sonija Nel, the company’s key accounts manager says Ecomed was faced with a significant increase in demand for oxygen during the first two waves. However, they were able to meet that demand. During the third wave, Ecomed found that they had to enhance the capacity of their staff and supply chains.

It doesn’t matter how many ventilators you invest in, we simply do not have the manpower nor the facilities to run them.

– Prof Rudo Mathivha, Head of Intensive Care services at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital

“Lessons learned during the second wave have helped increase capacity to meet demand in the weeks and months ahead. Patients suffering the worst symptoms of respiratory disease in the third wave caused a drastic increase in rental and purchase of oxygen requests in comparison with the first two waves,” says Nel. Ecomed also supplies “stationary oxygen to hospitals throughout South Africa”.

“We depend on suppliers currently under pressure to supply the quantities with the increase in daily infections. As a company, we are very fortunate to have good relationships with suppliers and have weekly orders of oxygen concentrators,” says Nel.

Other businesses that specifically look to work with oxygen, in a different way, have also taken the time to use their services to chip in with help during the pandemic.

Air Liquide, a French multinational company supplies industrial gases and services to various industries including medical, chemical, and electronics manufacturers in South Africa. In terms of the pandemic, Air Liquide says its teams are fully mobilized to address the need for medical oxygen in hospitals.

The company also has an oxygen production plant.

“The proportion of our oxygen production which is dedicated to medical use varies significantly depending on demand (which varies over time and geography). During Covid episodes, we make sure hospitals’ demands can be addressed as priority,” they tell FORBES AFRICA.

Should South Africa have been better prepared?

Professor Rudo Mathivha, Head of Intensive Care Services at Chris Hani Baragwanath Academic Hospital, the largest hospital in Africa and third largest hospital in the world, argues that it is more than a resource problem.

“It doesn’t matter how many ventilators you invest in, we simply do not have the manpower nor the facilities to run them,” Mathivha says.

Casey Moodley, a registered nurse (sister) who has worked in a Covid-19 general and high care unit during the first and second wave, agrees with Mathivha’s sentiment. She is preparing to work in a Covid-19 high care unit during the current third wave and comments on her concerns as a frontline worker.

“Our healthcare system simply cannot handle this,” Moodley says. “Even developed countries are suffering. We do not have enough capacity, equipment, and manpower but healthcare workers who are at the helm of this pandemic are trying our best to fight this horrible battle with whatever little resources we have.

“I have witnessed people dying in numbers, young and old. I have watched people gasp for their next breath, even the highest oxygen was not enough. The best medical intervention sometimes is not even enough. If the virus wants you, it takes you.”

The failing mental and physical health of these frontline workers has been extremely difficult to come to terms with for Biccard.

“Patients arrive, they have to be seen,” Biccard says. “But the staff are completely burned out. The nurses I work with have Post Traumatic Stress Disorder for sure. They’re exhausted. They can’t just keep these waves of patients coming in, sitting on the floor or sitting on wheelchairs. There comes a point where there needs to be state assistance of some kind.”

With capacity in hospitals being an unanticipated problem, especially bed shortages, and even with the vaccination rollout gaining momentum – though temporarily stalled in some parts during the riots in mid-July – it’s difficult to rule out that South Africa will have an issue on its hands like India did.

Bed shortages in South Africa, as authorities attest, have been a challenge since the start of the pandemic. Now in the throes of the third wave, this has only amplified. Biccard says government hospitals in South Africa are heavily overburdened. So when patients come to her hospital “we can’t just turn them away”.

People wait in parking lots to be assisted, ambulances queue up outside the ED and beds are not available until someone dies.

“It’s changed how we practise medicine completely because we don’t have beds to examine the patients,” Biccard continues. “We are seeing patients on chairs, you’re going out to the car to see patients. It is more like disaster management now.”

Moodley, who contracted the virus earlier this year as one of many healthcare workers who invariably did, adds: “It was one of the scariest and most stressful experiences. Seeing what happened to patients and what it can do made me fearful of passing it on to my family. I insisted on taking care of myself until I eventually felt better and it wasn’t contagious anymore.”

Mathivha adds that she is also concerned healthcare workers will be more exposed to infection despite being vaccinated.

“The vaccine only protects against severe disease; as they get infected, they will have to go into quarantine thus reducing the numbers at work at any given time,” she says. “Another serious concern is that the more people get infected, the more chance of them overwhelming healthcare facilities and overwhelming their capacities and us struggling to accommodate the disease severity.”

Mlisana agrees that the point that has been raised is critical as healthcare workers are essential now more than ever. They also play an important role in curbing vaccine hesitancy in the country.

With the previous waves, Mlisana says there were plans to address the mental health issues of frontline workers but she says that citizens should hold the government responsible for any promises made.

“The question then I would bring is whether those were followed through because sometimes we talk about issues when we’re going through a crisis,” Mlisana says. “[Then] we forget about them and life goes on.”

The cost of Covid in South Africa

It’s difficult to quantify what Covid has cost the country so far in monetary terms.

For one, the country faced an initial setback and delay when on the vaccine front, Ramaphosa announced that scientists discovered the AstraZeneca vaccine procured from the Serum Institute of India did not provide sufficient protection against the variant predominant in South Africa at the time.

In line with the national rollout plan, over a million healthcare workers have been vaccinated across the country and the registration and vaccination of this cohort continue.

South Africa has received an additional 1.2 million doses of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine and 1.4 million doses of the Pfizer vaccine through COVAX.

There has been a significant cost and numbers are still expected to rise especially when it comes to funding the vaccine rollout in South Africa.

“Just the Covid National Treasury alone is actually expecting to spend R19.3 billion ($1.3 billion) over the next three years on the vaccine rollout,” Mlisana says.

“I think what we can never compensate for is the cost of lives. Because I mean, we’re sitting at about 60,000 South Africans (in mid-July) who have lost their lives to Covid-19.”

Chance of a fourth wave?

According to Bloomberg, the Delta Variant may spark the fourth wave of infections in Kenya over the next two months.

Ahead of the local elections in October in South Africa, there is general concern that the majority of the country will not be vaccinated by then, which could lead to a potential spike in infection.

The former chair of the Covid-19 MAC, Salim Abdool Karim, agrees with the sentiment that there could be a fourth wave, but only in December.

“We won’t be able to stop the fourth wave, because you have to have a very high level of vaccination to stop a fourth wave. You’d have to vaccinate 70% to 80% of the population, which we would not likely achieve in time,” he told Bhekisisa. “But it will likely be a small, mini fourth wave.”

On the other hand, Biccard believes South Africa will not survive a fourth wave.

What we can never compensate for is the cost of lives.

– Professor Koleka Mlisana

“I don’t think the South Africa system can continue to sustain this if it carries onto a fourth wave. The nature of the virus is very lethal. Things can go bad very quickly. And I don’t think people realize it.”

So as of now, the fourth wave is riding on South Africa’s ability to get most of the country vaccinated. Mlisana says that the issue currently and why the third wave could be so detrimental is because the country has not been able to ramp up the vaccination process.

“We have seen a very slow uptake of registrations, and that needs to be dealt with. And so it’s going be a big challenge to see how we motivate South Africans to register,” Mlisana says.

“More citizens should have been vaccinated by now. It makes me uneasy because the Delta Variant is said to affect younger people but we have only vaccinated healthcare workers and over 60s (as of mid-July). Younger people can also have co-morbidities and are also dying from Covid-19,” says Moodley. “To me personally, the vaccine is like a ray of light in a dark tunnel.”

And hopefully, the tunnel will have an endless supply of oxygen to keep the sick going.

Loading...