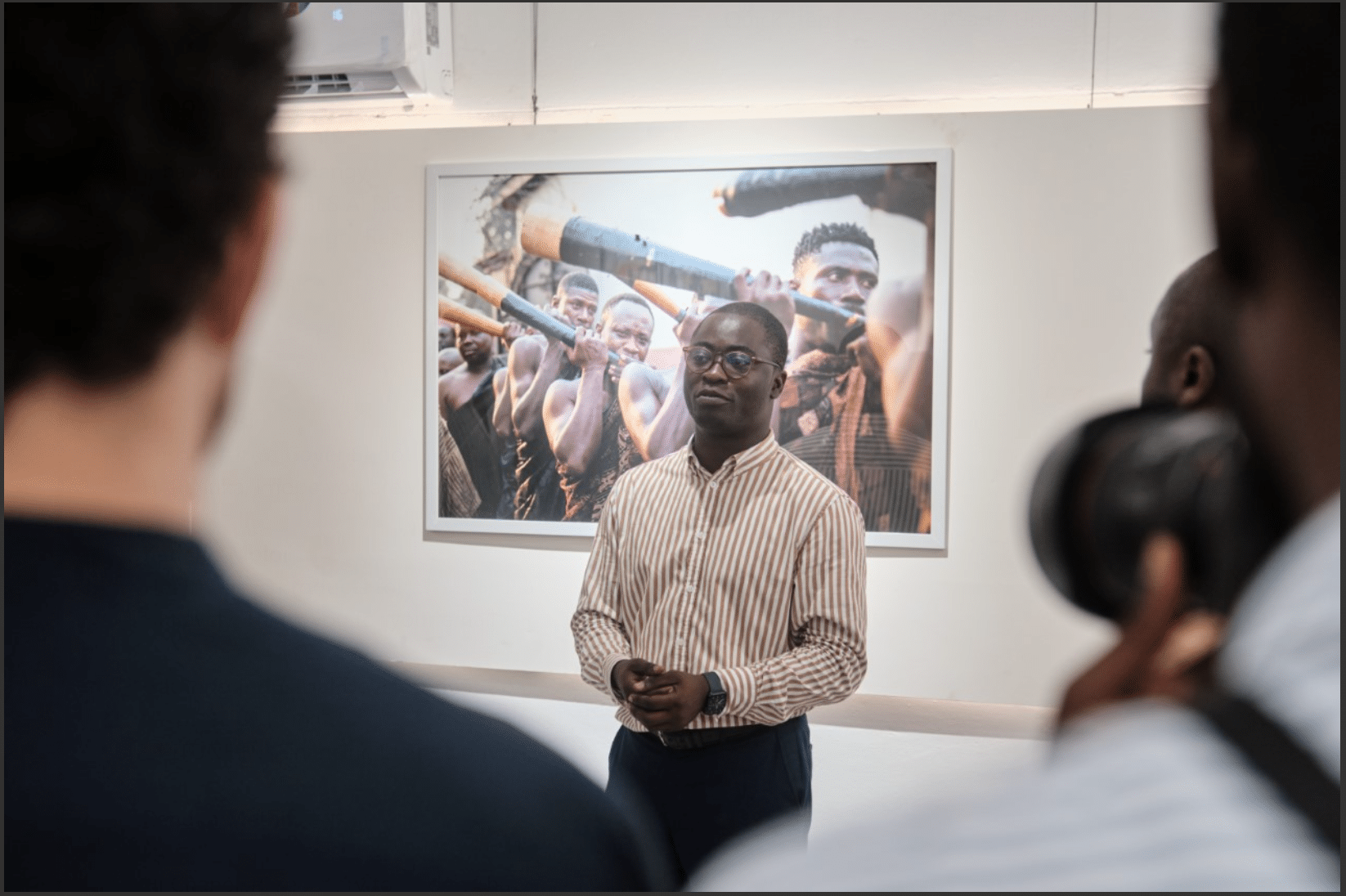

Ghana’s Dikan Centre that opened recently was a result of Paul Ninson’s need to get African creatives to tell the story only they knew best about the continent.

For as long as Paul Ninson can remember, storytelling has always been a part of his DNA. Growing up in Kumasi in southern Ghana with his grandparents, Ninson would fall in love with storytelling by listening to the many community and historical accounts of his village told by his grandparents and decided even from then, that he would contribute in some way to telling his own story.

“I was always looking for a way to express myself. I used to draw a lot when I was a kid and I studied visual arts in school. When I reached university, I studied textiles but it wasn’t enough for me,” says Ninson.

One day, a friend of his returned from the United States with a camera and that is when things began to get interesting. Ninson was introduced to a new world of photography. At the time, he had a side hustle creating graphic designs and printing T-shirts but he decided to wrap that business up and sold his iphone to get himself a camera too.

“I decided to use photography as a medium to express myself and tell my own story. I wanted to tell real stories of my experience as a Ghanaian and my experience as a young man growing up in Ghana and the things I know and things I’ve seen and things I am motivated to talk about,” says Ninson.

Loading...

To differentiate himself from the other Ghanaian photographers, Ninson adopted some ideas from a book he read called Blue Ocean Strategy. At the time, he was making ends meet as a photographer by taking images during events but he knew photojournalism was his true calling.

Instead of documenting his experiences in Ghana, Ninson decided to invest in telling more of a pan-African story. He saved up money and traveled to a village in Kenya famous for having no men and started snapping.

“My content was different and the pictures I was posting was different. That uniqueness earned me an admission to one of the best photography schools in New York, the International Center of Photography,” recalls Ninson.

All of a sudden, a world of opportunities opened up to Ninson. He spent his free time at the New York public library where he began to immerse himself in the thousands of books and images available to him. That was when he had his biggest epiphany about photography.

“I loved books and the library had pictures of thousands of images about Africa including one of Kwame Nkrumah (Ghanaian politician) which I had never seen before in my life. So, it triggered me to find out why these pictures existed in America thousands of miles away but not in Ghana or Africa for that matter. And that is how the idea of a photo library began.”

Ninson already knew he did not want to graduate and jump into the hustle and bustle of feeding the beast that was the American media industry.

“I did not want to join a queue of photographers waiting to just sell images to the New York Times for example. I was thinking about media in the grand scheme of things and I wanted to build my own ecosystem in Ghana rather than be in a queue and be a supplement to other institutions,” says Ninson.

Today, that small dream has evolved into “the biggest photo library in Africa” as Ninson calls it, the Dikan Center, which opened in December last year with 30,000 books. Ninson has built a media landscape in Ghana to finally empower him and other creatives to tell their own stories and also make

a living out of it. He began by sending books back home and started crowd-funding to raise $1 million to kick-start the center.

“I want to provide visual education for Africans. Now we are more than a library. We have education programs, we have a gallery that stands as a means of distribution. We also have a story lab and studios and a community center which is a space for people to come and enjoy free internet and resources for everyone to hang out and collaborate,” says Ninson.

Africa’s story has in the past always been narrated by outsiders and for people like Ninson, Africans are perfectly capable of telling their own stories. That initial love for storytelling which has followed him all his life has today mushroomed into a movement bringing together thousands of Africa-centric images told through the power of a lens and perhaps most importantly, by African creatives.

Loading...