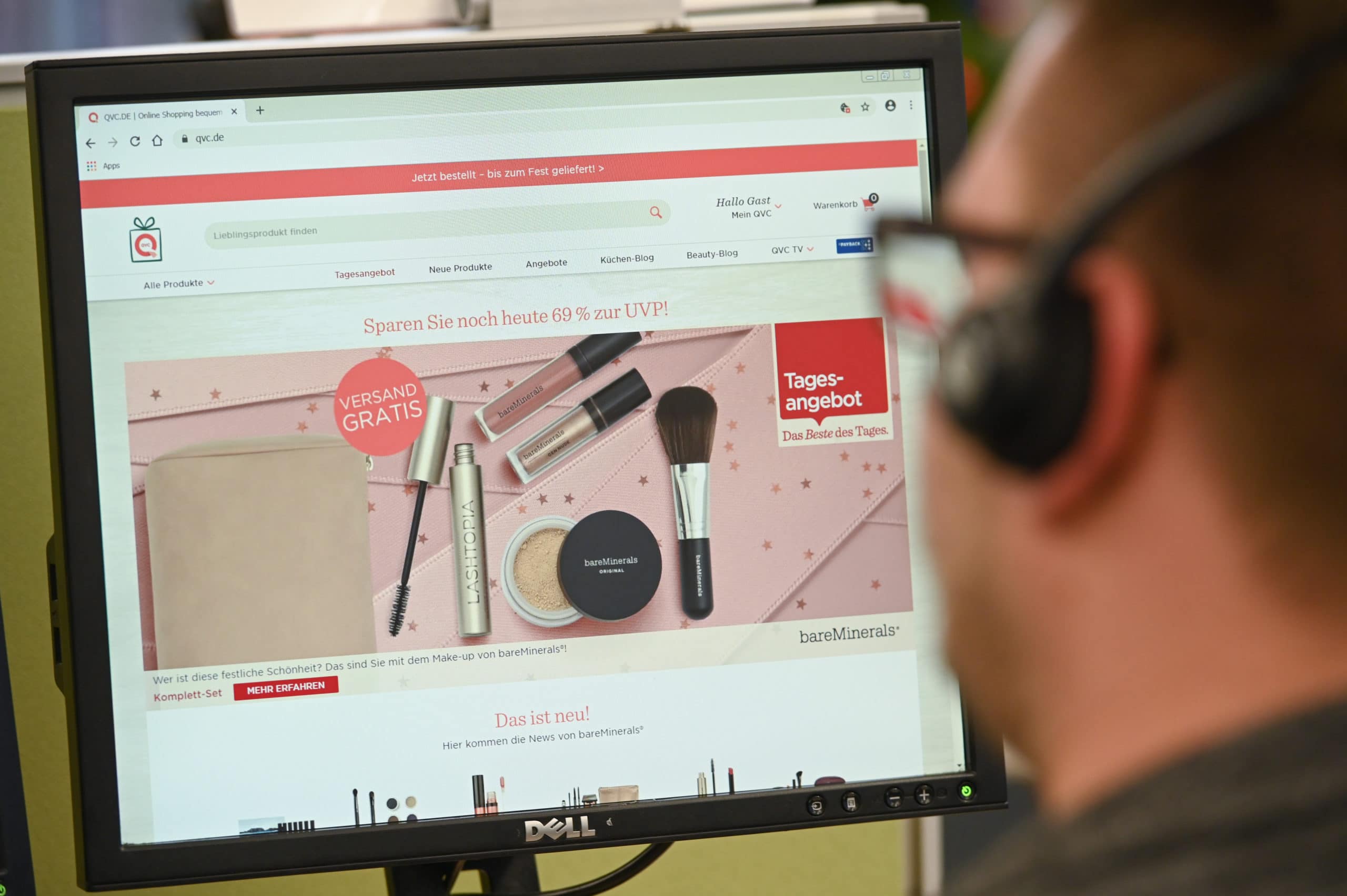

Amazon, Facebook, TikTok and a growing number of venture-backed startups are all seeking to replicate QVC’s success selling stuff via live demos and time-pressured promotions. But the original home shopping is still way ahead – for now.

In March, a year into the pandemic, QVC is pitching a predictably eclectic assortment of items. A set of three collapsible storage boxes for $33, perfect for the springtime ritual of clearing away clutter — 28,000 sold! A pink amaryllis bulb for Easter – yours for three payments of $10.89! An “ingenious” planter in the shape of a frog — only 500 left!

Hardly the essentials needed to endure a lockdown, but it’s made for brisk business for QVC and its sister channel HSN, which now reach into 380 million homes worldwide and continue to find a massive audience for its hokey sales pitches that push everything from mattresses and mops to cooking supplies and jewelry.

Last year, the two channels — plus a handful of smaller clothing and home décor brands — delivered revenue of $11.4 billion for publicly-traded Qurate Retail. QVC has been around for 35 years but has suddenly become the company to beat in the industry’s new fervor for live shopping. Amazon, Facebook and TikTok are in hot pursuit, along with a number of venture-backed startups. Walmart wants in too, as do Macy’s, Nordstrom, Urban Outfitters, Wayfair, Estee Lauder, Tommy Hilfiger and Levi Strauss, all of whom have begun to experiment with the approach as a way of reaching shoppers who are staying at home — and may never come back.

“They are more relevant now than ever,” says Neil Saunders, managing director of GlobalData Retail, of the two channels born at the dawn of the cable TV era.

Loading...

Livestream shopping, the internet-era name given to programming that leans heavily on lively demos, time-pressured promotions and real-time interactions with shoppers, is set to grow four-fold to $25 billion in the U.S. in the next two years, according to Coresight Research. And that’s nothing compared to what’s happening in China, where data firm iResearch expects consumers to spend $300 billion on livestream purchases this year, about 15% of the country’s total online sales. Qurate, with 22 million active customers, is the largest in the U.S. by far and still growing, adding 7.6 million new shoppers during 2020. Shares of Qurate, which is controlled by cable billionaire John Malone, have delivered total returns of 300% in the past 12 months.

“The world is shifting to what we do,” says Qurate CEO Mike George, who is set to retire at the end of the year. “As we see others copy what we do, it motivates us to move that much faster to expand our leadership.”

While most livestreamers are still fumbling for footing, QVC is a well-oiled machine that has already won over millions of bargain-hunting, middle-aged women, who buy an average of 26 items every year at a cost of $1,335, an enviable advantage. Big tech is still in the trial and error phase. Amazon’s first effort, “Style Code Live,” was cancelled in 2017 after a year. The online behemoth has since revamped the strategy to allow brands and influencers to host their own livestreams, which run throughout the day on the Amazon Live page. Last year, Facebook began making it easier for small businesses to sell products during livestream sessions, while TikTok is running tests with Walmart. A pilot event in December attracted seven times more viewers than it anticipated, prompting a second livestream earlier this month.

A rash of copycats has also emerged, with ambitions of overtaking the incumbent with a slicker, more digitally savvy version geared toward young shoppers. “I love it,” says George, who keeps a thick file of stories about companies purporting to be the ‘new QVC,’ most of them failed. “It’s good to be talked about.”

If any of them do gain traction, they could threaten the value of that 380-million home reach. That’s why George has embraced streaming services like YouTube TV, the company’s own branded websites and mobile apps, as well as social media. He’s now testing 15-second spots on TikTok and on-demand content like a 30-minute show where celebrity chef Curtis Stone travels to far-flung destinations to sample local cuisine. A new app, currently in beta in the U.K., will let users themselves livestream content, the same kind of user-generated content approach that has boomed in China.

The world is shifting to what we do. As we see others copy what we do, it motivates us to move that much faster to expand our leadership.

George won’t disclose how many orders still start with a customer tuning in through their television, and instead points out that QVC and HSN are now mostly digital businesses, with about 60% of their revenue coming from online sales and two-thirds of those purchases made from mobile devices. Still, sales rose just 5% in 2020, hardly the numbers posted by a game-changing growth business.

The 59-year-old retail veteran began running QVC in 2005, shortly after cable giant Comcast sold its stake in the business to Malone’s Liberty Media Corp. in 2003, and oversaw the 2017 acquisition of its main rival, HSN. Before he took the job, he was put off by what felt like a dated concept even then, but was won over by its connection with customers and the way it sent units flying out the door. The son of a carpenter who learned as a kid he was no good with his hands, George became convinced that QVC’s “best days were yet to come.”

“The people that watch QVC and HSN and buy stuff on there woke up that morning and didn’t know they needed a pan or makeup or whatever it is,” says Evercore ISI retail analyst Oliver Wintermantel. Its biggest problem? An aging audience.

That’s what led him to pay $2.4 billion for flash sales site Zulily in 2015, giving him a brand that also relies on time-pressured promotions but is popular among moms with young children. He also ramped up the marketing budget for QVC and HSN to $170 million last year, with a focus on social media ads and partnerships with influencers.

George says he’s got the problem in hand, but not because he believes that youth is the future. Gen Z shoppers lack the disposable income, hobbies and life experience to be interested in what he’s selling. “We’ve never worried a whole lot about being cool,” he says. Instead, he sees plenty of runway left for his core audience of women 35 and older.

His bigger worry is becoming a showroom for Amazon. That’s led to exclusive merchandise deals, both with emerging entrepreneurs like IT Cosmetics founder Jamie Kern Lima and celebrities like Katy Perry, Martha Stewart, Jaime Foxx and HGTV’s Property Brothers, who are drawn to the company’s massive reach.

One of those lines was with plus-sized model Hunter McGrady, the curviest woman ever featured on the cover of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Issue, who watched QVC with her mom growing up and debuted a clothing line with the channel last year. She worked with the in-house design team to create a line of hoodies, joggers and cardigans in sizes XXS to 5x, then began going on-air to walk customers through the story behind each piece. Doing it live she can demonstrate how the clothing moves on her body. On one segment, the 27-year-old explained how she created a ruched tank top because she could never find one that sufficiently covered her backside. She has sold 155,000 units since launching last April, most to customers she never would have reached on her Instagram page.

“I think what a lot of livestream shopping folks miss is they’re trying to sell you something in the moment with technology, a flashy influencer and slick production values,” says George, who says his viewers often watch hours and hours of programming before springing for a purchase. “They’re not establishing any connection, relationship or intimacy with you. They’re not enticing you to come back tomorrow to discover something new. That is the magic of what we try and do.”

-by Lauren Debter,Forbes Staff

Loading...