Improving yield, efficiency and profitability in agriculture comes down to the harvesting of technology. At its forefront are the agritech innovators bringing transformative change to the continent’s green economy. FORBES AFRICA profiles some of Africa’s biggest agripreneurs, inventors, and agribusiness leaders changing the way we think about farming, food security and climate resilience. They have cultivated a passion for smart agriculture and are leading the charge for social change not only for the sector but for the continent – and for humanity’s sustainable future.

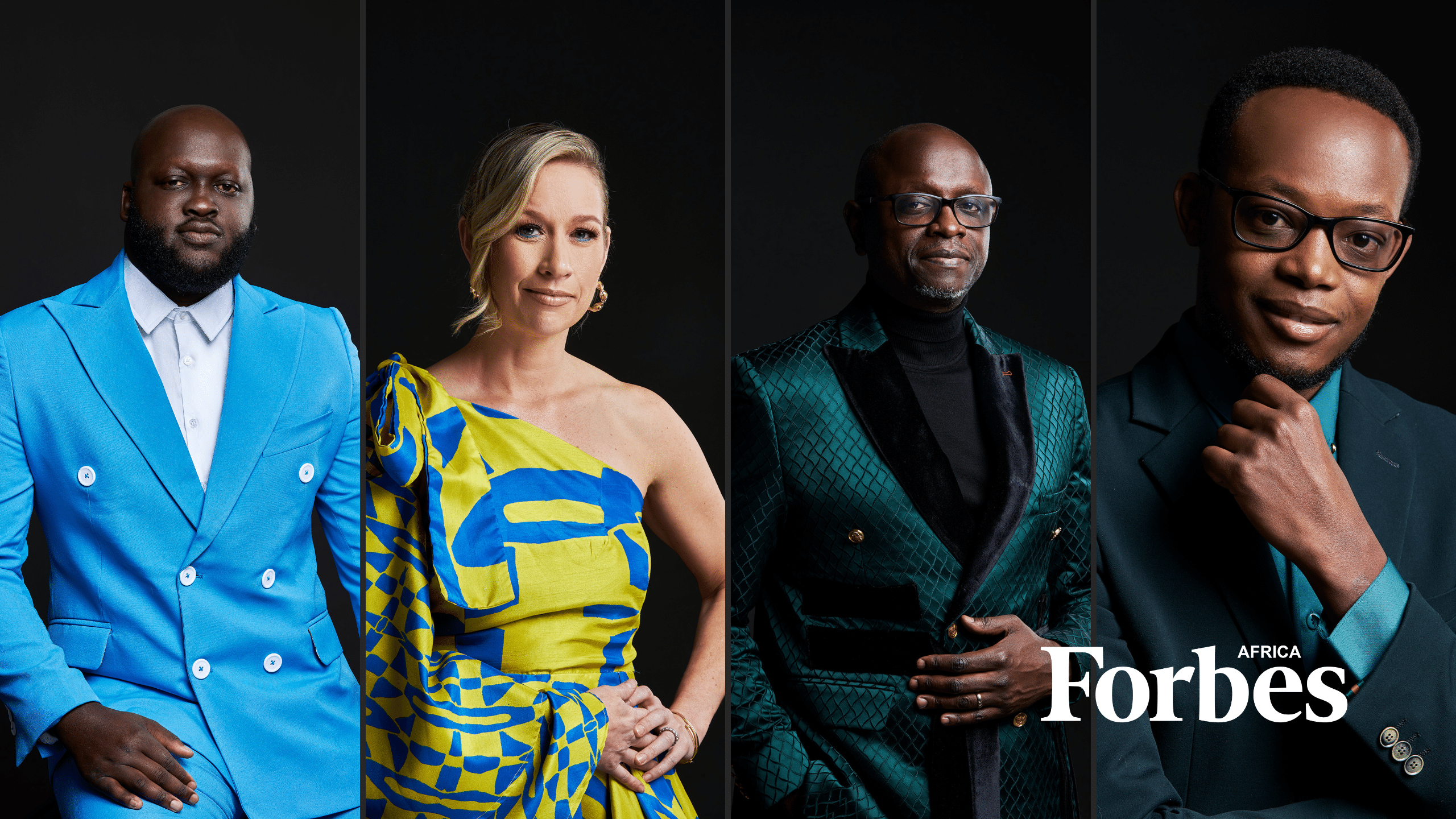

Words and Curation: Chanel Retief and Lillian Roberts

Art Director: Lucy Nkosi Photography: Katlego Mokubyane

Photography Assistant: Sbusiso Sigidi Studio: NewKatz Studio, Johannesburg

CNBC Africa Videographer: Thabo Mathebula

Video Editor: Chanel Retief

Styling: Bontlefeela Mogoye and Wanda Baloyi

Outfits supplied by: Kworks Design; Imprint South Africa; House of Suitability; LSJ Designs

Hair & Makeup: Makole Made

“What are you looking at?” Dr Agnes Kalibata asked the smart young businessman standing next to her at a summit in Kenya, who seemed suddenly distracted, looking at his phone.

“‘I am checking on my cows in the Ivory Coast’, he said to me,” says Kalibata, the Rwandan agricultural scientist and policymaker, and President of the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA).

“Then he said ‘I installed solar cameras all around my farm, which is a side hustle for me, so that I can check on my livestock whilst I work here in Kenya’.

Loading...

“For me, that’s the future of farming!” exults Kalibata.

It all boils down to not just crops or copses, flower beds or bouquets.

It lies in the innovations sown into the evolving landscape of agricultural technology or agtech/agritech.

And these agripreneurs don’t mind getting their hands dirty either – beyond their smart business suits. The opportunities for them are immediate and ripe for the picking.

“What we’re seeing happening in the space, is a higher uptake of technology,” says Dr Mandla Mpofu, the Managing Director of Omnia’s Agriculture Division, to FORBES AFRICA.

Ominia Group specializes in conducting research and development, manufactures and supplies chemicals and specialized services and solutions for the agriculture, mining and chemicals application industries.

“By technology I just don’t mean the electronic side of it but also understanding the industry a bit better. So what I’m talking about here is understanding the soil, working on improving yields. And then you have satellite technology being used and we’re seeing artificial intelligence coming into this very, very exciting industry.”

Kalibata tells FORBES AFRICA that the agricultural sector has really been defined by the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

“There are specific moments in time that completely change how we think about business and how we do business,” Kalibata adds. “So specifically, this particular revolution, I would say, there’s a real revolution happening from an agtech perspective… This is why there are so many new ways of looking at how agriculture can be done, all the way from how we generate the technologies that we use.”

One of the biggest issues Khadija Mohamed-Churchill, founder of Kwanza Tukule in Kenya, encountered when she began in this industry was the food supply chain.

“It’s really difficult to solve but can be solved. Also, the investments don’t want to flow there. Investment wants to flow into things like unicorns or fintech. I mean, people have to eat. They will transfer money via mobile phones, they’ll take loans, but if they don’t have food, at some point, the priorities need to shift to focus on these fundamental things,” Mohamed-Churchill explains.

Let’s take a step back.

In 2022, the World Economic Forum estimated that there are well over 600 million smallholder farmers around the world working on less than two hectares of land. These farmers are estimated to produce 28%-31% of the total crop production and 30%-34% of food supply on 24% of gross agricultural area.

A further study done by the United Nations showed that the world population will reach 9.1 billion by 2050, and to feed that number of people, global food production will need to grow by 70%. For Africa, which is projected to be home to about 2 billion people by then, farm productivity must accelerate at a faster rate than the global average to avoid continued mass hunger.

In sub-Saharan Africa alone, there are over 400 agritech solutions and startups, according to a 2020 report by the global telecoms industry lobby GSMA. Agriculture makes up 35% of Africa’s GDP and employs about half of its people, but the continent still imports billions of dollars of agri-products every year.

“From the outside, agriculture looks pretty dirty,” the CEO and co-founder of Khula!, Karidas Tshintsholo, says to FORBES AFRICA. “But I’m a numbers guy… Once I started looking at the numbers and saw that we [Africa] have most of the world’s arable land, which is 60%, is here are the ones [with] remaining arable land. Almost everybody on the continent is dependent on agriculture for survival.”

“I would look at agriculture in terms of the size of the opportunity,” Peter Njonjo, theCEO and co-founder of Twiga Foods in Kenya, adds.

The opportunities may look monetary but for a number of the agritechs, especially the ones we looked at for this feature, it’s about two mutually exclusive yet different reasons – solving food security on the continent while becoming climate-resilient.

“The yields of certain crops in Africa have already dropped by several percentage points, because of warming and drought. So, it’s already happening. So, you can’t possibly talk about sustainable agriculture without talking about climate change,” says Professor Guy Midgley, Head of the School for Climate Studies in Stellenbosch University, South Africa.

In a report by Deloitte, with about 60% of the world’s uncultivated arable land, as Tshintsholo previously states, Africa has the capacity to meet the world’s long-term food demand.

In addition, land already under cultivation could produce much more but crop yields remain at half the global average.

With the right know-how and inputs, Africa’s average cropland productivity can more than double. Coupled with positive global food demand, Africa’s underutilization of its land resources for farming implies significant growth opportunities for agricultural producers and exporters in Africa.

For Midgley, it comes back to the fact there needs to be a better understanding of the integrated challenges. According to him, Europe and North America have access to what are called integrated assessment models (IAM). These models aim to provide policy-relevant insights into global environmental change and sustainable development issues by providing a quantitative description of key processes in the human and earth systems and their interactions, which, as Midgley assesses, are “really important and really valuable for asking questions about our policy”.

“We’ve been late or rather our politicians have been late to realize the potential benefits of a green economy,” Midgley adds. “I think we need as a region a much better understanding of the integrated nature of these challenges… Our policy might sustain food security, within the constraints of water availability, within the constraints of fertilizer requirements. We don’t have available to us to inform the policymakers of what is the best combination of scenarios going forward. There are many scenarios that would get us to a sustainable future, which would balance the interests of different countries on this continent.”

Kalibata’s view holds a different approach and one where we need to address these issues from a more holistic scientific perspective, which will help tackle food security.

“I actually think that the future of agriculture is smaller than 60%,” she says. “We don’t need 60% of land to drive agriculture. Some young people are already beginning to farm vertically, right? And we recognize that some young people are already beginning to use what it is called hydroponics, recognizing that you don’t need soil, and now let’s produce food… In Singapore, you see people making chicken using stem cell research.”

Although the innovators featured on these pages are not dabbling in stem cell research, the solution for these agripreneurs is ensuring that accessibility is at the forefront of all their work and ideas. Studies have shown that in most African countries, agriculture accounts for 70% of the labor force, over 25% of GDP and 20% of agribusiness.

Agriculture remains largely traditional and is concentrated in the hands of smallholders and pastoralists, the Economic Report on Africa 2009 stated. Often women provide much or most of the labor, but don’t reap the economic benefits.

“I think that it is often misconstrued that farmers are not willing to adopt tech,” Tshintsholo says. “But I think if you’re able to speak to them [about] their pain points, inputs, selling their products and financing, you will find that the uptake is actually quite high. And I think one of the lacking factors is solutions that actually speak to the real pain points farmers are facing.”

“I think tech could be most impactful in a continent like Africa,” Njonjo adds. “Where we have the largest inventory of cultivated farmland on earth or the continent is both important strategically for the global food system. But also, when it comes to stabilizing the economy, this is where more the impact and kind of social mission of the company comes in.”

FORBES AFRICA speaks to some of the leading agri-players tackling farming tech and trends and feeding the continent.

Brian Bosire Founder and CEO, UjuziKilimo

Kenya

Four years ago, Brian Bosire told FORBES AFRICA that his hope for UjuziKilimo was that it would reach over 10,000 farmers. Speaking to us during the photoshoot for this feature at the NewKatz.Studio in Johannesburg, he tells us he has now reached over 26,000 farmers.

“Our vision is really to see a world of empowered smallholder farmers working at the cutting edge of technology in terms of how they make decisions on the farms, how they access financial support, and also the knowledge they need to improve productivity from the farms,” Bosire says.

Bosire’s passion for smallholder farming started as a boy in a small town in southwestern Kenya known as Kisii.

“I come from a farming village in Kenya, and my parents–their first career was farming,” Bosire says. “They were smallholder farmers, so as I grew up, it formed the core of what I understood about food production and the economy; a sole source of livelihood in our family.”

The ESRC STEPS (Social, Technological and Environmental Pathways to Sustainability) Centre concurs with Bosire’s assessment that smallholder farmers are key to the country’s food security and economy. “Small farms account for 75% of the total agricultural output,” ESRC STEPS Centre writes in a 2023 report.

Bosire, as a qualified engineer, wanted to find solutions for these farmers that would not only be beneficial to them from an economical perspective but from a social one too.

And with that, his business was born. UjuziKilimo–which is Swahili for ‘knowledge farming’– processes millions of data points each day to create a complete soil and agronomic data pool that is both field specific and highly accurate.

Soil Pal, a handheld sensor, acts as a soil parameter to quickly and easily measure the content of the farmer’s soil, and produce the right amount of data for the farmer to receive actionable information within five minutes on the best crops that will do well on the land and the fertilizers they would need.

Part of the UjuziKilimo experience is also FarmSuite, which is a complete farm management, predictive farm analytics, intelligent insights and recommendations software to power decision-making for farmer groups, co-operatives and service providers.

“Our technology is actually ensuring that farmers are moving away from guesswork. Because traditionally, farmers have been led by intuition to make decisions on which crops will do well.”

Part of this empowerment is looking at how much opportunity lies within the African landscape when it comes to agriculture and technology.

“We also understand that unlike developed countries, Africa is the place of opportunity when it comes to the uptake of technologies that we’re seeing and developing at the moment,” Bosire adds. “The fact remains: smallholder farmers form the majority of the people producing food at the moment, but unfortunately, you still realize that a majority of those farmers are living below $2 or $3 per day.”

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization’s report, The Economic Lives of Smallholder Farmers, three billion rural people live in about 475 million small farm households, working on land plots smaller than two hectares. Smallholder farms in Kenya are only marginally large as they are 0.47 hectares and in Ethiopia the average small farm size is 0.9 hectares.

“Many are poor and food-insecure and have limited access to markets and services. Their choices are constrained, but they farm their land and produce food for a substantial proportion of the world’s population. Besides farming, they have multiple economic activities, often in the informal economy, to contribute towards their small incomes,” the report read.

For UjuziKilimo, it’s about seeing smallholder farmers get a return on their products as they contribute to the future of food. The data that is being collected from the soil as well as the interaction with farmers is what Bosire actually uses to ensure these farmers have access to aspects like insurance and financing, “because of the richness of the data that we have can be developed over time”.

Gugulethu MahlanguFounder and CEO, House Harvest

South Africa

In 2018, Gugulethu Mahlangu went home to the rolling plains of the Highveld in South Africa. In a landscape dominated by livestock farmers, she planted cabbages, only to soon find them waterlogged.Counterintuitively, this first failure was the moment she realized she was going to be a farmer.

“I found that there’s just so many numerous opportunities, especially for young African women. That’s just what made me cultivate the love for agriculture, because before I really felt like it was roses and sunsets, but when you get in the industry itself, you realize that it’s a lot of work. It’s patience, it’s money, it’s time, it’s investing in trying, learning, and picking yourself up back again.”Mahlangu describes aquaponics as a soilless farming method.

She uses the Deep Water Culture (DWC) method.In DWC, the nutrient-rich water is circulated through long canals while rafts float on top, according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). The plant roots hang through holes, absorbing nutrients and oxygen. According to the FAO, this method is commonly used for commercial aquaponics with a high stocking density of fish.

Mahlangu explains that fish provide 10 out of 13 nutrients plants need.“It’s economical once it starts, and can provide you with a system that can employ people all year round, because it runs all year round.”Mahlangu says aquaponics is a climate smart-solution to agriculture. Unlike traditional agriculture that is seasonal and based on economies of scale, aquaponics requires limited space.“Global warming isn’t a regional issue. It’s not an African problem. It’s a planet problem. So, we are contributing to that positively.”

Technology like aquaponics can be a method of alleviating food insecurity in densely-populated and urban areas.“Apparently, they say in South Africa, we are food secure. But we are insecure in the way that food gets accessed. Here comes a solution like aquaponics or vertical farming saying ‘I can meet you where you are, I can meet you on your balcony, I can meet you in your township, in your limited space’.”She has worked as an aquaponics horticulturist at Finleaf Farms. Now, Mahlangu has returned to her hometown of Witbank in the Highveld of Mpumalanga, South Africa, to build her own facility, named House Harvest, in an urban setting.Focused on trial and error, she’s going to gather her own data in the South African context before acquiring an investor and scaling. Since aquaponics is a high investment, she wants to produce high value crops to get an ROI as quickly as possible, focusing on restaurants.

As a 29-year-old emerging farmer, she understands the challenges in this sector.

Peter Njonjo Co-Founder and CEO, Twiga Foods

Kenya

“Our story started with a banana.”

“Yes, a banana,” Peter Njonjo attests, as he sits down, adjusts his glasses and looks right into the camera reminiscing the beginnings of one of Africa’s most influential companies–according to Time Magazine–Twiga Foods.

“And the key thing here was that bananas in a supermarket in London were cheaper than they were in a supermarket in Nairobi.” This was strange for Njonjo as the banana in the London supermarket had traveled over 4,000 miles from Latin America to the United Kingdom. However, the banana in Nairobi had merely traveled 400 kilometers.

“And we asked ourselves, ‘why is this the case’? And by answering that question, we started uncovering the issue around food inefficiency.” Njonjo’s belief is that in Africa, the retail industry is fragmented by the many “middlemen” involved in the supply chain moving food from farm to the table.

“We realized that sometimes a banana has been touched by five to six people before it gets to the retailer.

In the course of that [time], half the produce is actually lost to poor handling and post-harvest losses. So that level of waste, that level of inefficiency was contributing to the high cost of food on the continent,” says Njonjo.

At least one in five Africans goes to bed hungry and an estimated 140 million people in Africa

face acute food insecurity, according to the World Bank Global Report on Food Crises 2022 Mid-Year Update. Furthermore, a 2022 World Resources Institute report found that around a third of food produced globally is lost or wasted, resulting in economic losses of an estimated $1 trillion a year. In sub-Saharan Africa, the estimate is roughly 37% or 120kg-170 kg/year per capita.

“Food loss and waste leads to reduced economic returns for farmers, and the water, fertilizers, energy and land used in production also go to waste. Such loss and waste drives expansion into fragile ecosystems, accelerates deforestation, species extinction and contributes to 8%-10% of annual greenhouse gas emissions,” the report said.

“What we wanted to do is develop an alternative system that allows us to reengineer this whole supply chain to digitize it and get to a point where we can shorten the cycle between the farms, and the retail and also reduce the amount of waste,” Njonjo explains. Twiga Foods uses technology to build supply chains in food and retail distribution on the continent, starting with Kenya.

The company inspired by the banana is now reportedly worth $300 million.

“The amount of food and beverage consumed in informal retail across the African continent is worth $700 billion. And if 50% of Africa’s disposable income is going to food, it means that that’s where the bulk of expenditure is at; that’s a bulk of [what] the opportunity is.”

“So the way we’re looking at it is we’re simply fishing where the fish are. The reality is that being in food on the African continent is an amazing space to be.”

Spencer Horne

Founder and CEO, Cloudline

South Africa

Savoring the mild nippy weather in New York City, a far cry from South Africa’s autumn sun, Spencer Horne seems to have come full circle.

The Spencer Horne who was born in the small community of Kales River, Cape Town.

The Spencer Horne who, from an early age, developed “an obsession” for engineering fueled by his love for trains.

The Spencer Horne who grew up as a dreamer and has always been keenly aware of this rhetoric of structure versus agency; what determines outcomes for individuals or communities?

The Spencer Horne who is in New York, a long way from home, ready to answer this question with regard to his business, Cloudline.

This should be a full circle moment for him, but it is not.

“It doesn’t seem like it because I feel like the work is only just beginning,” Horne chuckles in a Zoom interview with FORBES AFRICA.

Using battery- and solar-powered propulsion to deliver carbon emission-free flight operations, Cloudline is an aerospace company building a network of autonomous airships that delivers goods and services across the globe. According to Horne, air is an “underutilized resource”. Getting anything into the air in general is difficult as also expensive. “[For conventional aircraft], putting those aircraft in the air comes at a high capital cost and keeping them there comes at a very high energy cost,” Horne elaborates. “That’s expensive in monetary terms; it’s expensive in carbon terms. And we are at the heart of the technology that we’ve developed to address those two major barriers to more widespread use of the air for getting things done.”

When Cloudline started out, they identified the infrastructural gaps that exist within African regions and saw a massive opportunity.

This is the key role that Horne plays in the agricultural space. Although he does not constitute Cloudline exclusively as an agritech, their business contributes significantly to farmers.

“I think in the agricultural sector, in particular, we’ve seen the role data has played in transforming the way in which precision agriculture is being done.”

Precision agriculture is a part of the larger conversation around the green revolution. According to experts, this way of farming uses data from multiple sources to improve cultivation for farmers, whether it is used for crop yields and/or to increase the cost-effectiveness of crop management strategies including fertilizer inputs, irrigation management, and pesticide application.

Afgri, a South African agricultural services company, thinks of this type of farming as “site-specific and information-specific”.

“If you think about Cloudline in the context of the way in which data is gathered today, that’s against the backdrop of satellites…so this is one of the big places where Cloudline plays a role in that agricultural revolution. And to tie it in with more mainstream applicability, and lowering costs, we can think about the ways in which that grows these markets. From just the top-tier largest commercial farms, it makes it

more accessible to more people. That is the kind of thing that makes both business sense and development sense.”

Desmond Koney

Co-Founder and CEO, Complete Farmer

Ghana

There is no manual or playbook to tell you how to run a farm or even scale a business, as this agripreneur will tell you.

“I think a lot of times, especially for solving problems in Africa, you always underestimate then infrastructure gap that your solution needs to get to market,” Desmond Koney says to us from his home in busy, bustling Lagos.

Complete Farmer was built connecting three integral parts of agriculture; buyer, grower and vendor, connecting farmers to global food buyers and growing with them to provide a competitive edge across the supply chain.

“I asked myself ‘how can we start looking at farming differently’?”

Koney went to the drawing board not as a farmer but as a qualified engineer who wanted to bring more success to the sector on the continent.

“I started thinking of the problem from an engineering perspective. Like, how would I have done this, if I were designing a factory or if I were using my production engineering skills to approach the problem of

farming in Africa?”

According to Koney, the reasons why African farmers struggle to scale and sometimes ultimately fail are

because the continent has supply chain as well as capital issues.

The AfCFTA: A New Era for Global Business and Investment in Africa report by the African Continental Free Trade Area reiterates that already the pressure on Africa’s food supply will require substantial investment in order to guarantee food security, as the continent remains the only region yet to experience a Green Revolution.

“So Complete Farmer really started with the question of how do we improve and digitize the African agriculture value chain,” Koney says.

“We did not have a clear path…I wanted to build but first we really had to figure out what the solution really is. And we spent close to five years refining the model to where we are today.”

Complete Farmer is an end-to-end digital agriculture platform that provides industries with an easy way to cheaply source quality farm produce and it offers individuals anywhere in the world a convenient way to own a farm by eliminating the middlemen and farm produce aggregators. The marketplace platform allows global industries to build the supply chain and solve their agricultural needs directly, these are then exclusively brought by African farmers.

“We’ve seen that data about what the potential for agriculture is in Africa,” Koney adds. “And then we’ve also seen that data for how food insecurity is increasing, especially with what’s going on in Europe.

And given that we are talking about food, which is really something basic for human survival, this is what makes this industry full of opportunity.”

Nicole Rogers Co-Founder and CEO, Butterfly Foods

(previously Drawdown Foods)

Kenya

Covid-19 halted business, leading to lives and livelihoods lost and ruined economies worldwide. For Nicole Rogers, it had the opposite effect.

“During Covid-19, we really took the plunge because we were able to insulate in Kenya for a bit and I got a huge opportunity to incubate my own ideas,” Rogers says. “…But we have a really audacious dream. And we know people and we know things that can help the dream be realized and we’re willing to take risks.”

As a purposeful entrepreneur, what drove the Canadian-born CEO to the bread basket of Africa and this dream was the law of economics.

“Kenya has a strong and established horticultural export value chain…And so a lot of the produce that consumers in the United Kingdom and Europe are purchasing is grown in Kenya.”

But it also started with a strong sense of taste, and flavors, in becoming a part of Africa’s food flavor and enhancer market, forecast to witness a CAGR of 5.12% during 2020-2025, according to a report by Mordor Intelligence.

When considering starting a plant-based B2B ingredient company (now Butterfly Foods) transforming regenerative grown crop inputs into high-quality flavors for today’s leading food brands, the one question on Rogers’ mind was why some foods taste better in some regions and are different in others?

This research led her to the soil and improving soil health. According to Rogers, when you have scaled operations or have big farms, growing one single crop could lead to the crop losing its intimacy with the soil, thus the flavors then get lost, sometimes even the nutrients.

“For me, what sustainability tastes like is Africa,” Rogers explains. “Like truly, it tastes like Africa does–it’s a nuance of flavors. It depends on the soil. It’s crazy…And it’s really unique to Africa; I don’t see how you could do it in a lot of other places. You can’t do this in Europe!” She also works a lot with women as she believes women always have a better palate, with the ability to identify flavors such as bitter, sweet, and sour more strongly.

Jehiel Oliver

Founder and CEO, Hello Tractor

Kenya

Chatting to FORBES AFRICA from Nairobi, Jehiel Oliver recalls how he started a business on the Hello Tractor platform where farmers could make up to $30,000 in bookings a year.

“I’m from the US, and started my professional career in finance,” Oliver says. “But in [my] mind, I always wanted to do work that was meaningful for my community and I came from parents who were kind of pan-African in their view of the world.”

When a young Oliver left banking and started doing consulting work, “mostly still in finance”, he looked at deal structuring for funds investing across the Global South which then led him to agriculture.

“That’s where I uncovered the importance of agriculture, the role it plays in Africa’s economy and future economic growth,” Oliver says.

Hello Tractor, a Kenya-based smartphone app that connects small-scale farmers with nearby tractor owners, was built on understanding how much access smallholder farmers have to the basic needs of farming.

According to The Economist, in sub-Saharan Africa, 60% of crops are ploughed by hand, which in turn impacts the productivity of farmers and eventual crop yield. This is why over 220 million farmers in Africa live on less than $2 a day.

Oliver reiterates that smallholder farmers don’t have the machinery they need to fully cultivate occupied land. Tractors andfarm equipment are expensive, and financing is virtually non-existent.

“For us, it was about economic growth and prosperity for these African economies,” Oliver adds, “starting in a rural sector, you have low-income populations underserviced by just about every part of the economy, and seeing an opportunity to commercially serve these economic actors, these farmers, who are also entrepreneurs themselves.

“And to serve them in a way where they can grow their productivity, they can grow their income, they can send their kids to school, and not pull their kids out of school to work the fields.”

Nomhle Mliswa

Founder and CEO, Summerhill Farm

Zimbabwe

Farming is not for the fainthearted,” Nomhle Mliswa says to FORBES AFRICA in the middle of her harvesting season. Mliswa founded Summerhill Farm in 2007, a 345-hectare farm located in Doma, Mhangura, in the Mashonaland West Province of Zimbabwe. She employs 350 people, two-thirds of which are women. She offers one of the few tillage services in Zimbabwe providing tilling for other farmers.

The mixed farming includes small grain crops, maize, soya beans, potatoes, wheat, cattle, chicken, and goats. Mliswa uses smart agriculture practices: precision farming, a zero-waste policy based on a Just in Time strategy that ensures the swift delivery of goods and land profiling to ensure mitigation and adaption, water harvesting, storage and drilled boreholes.

Summerhill Farm adheres to Sustainable Development Goals, namely SDG 13 on Climate Action, Environmental Management and Conservation, as well as employment structure informed by SDG 5 on gender equality, offering equitable practices for both male and female employees.

Employees also get sanitation and decent housing, informed by SDG 6. Mliswa has established a local school for young children and a clinic within Summerhill Farm, in line with SDGs 3 and 4. This allows the women to work and maintain their families. The farm also has a shop for employees, sponsored ball games for the community, and employees are given potato and chicken rations, in line with SDG 1 and 3.

There is a Climate Desk, assisting local farmers with critical weather information. And Mliswa does not shy away from further CSR–the farm assists with repairing local road networks and bridges. Summerhill Farm is run by a single mother with a spinal injury–but neither of these things has held Mliswa back in creating a successful diversified farm using smart agriculture. She wants to do more for preserving the environment, implementing mitigation measures, creating awareness with women on global warming, and hosting more educational tours for schoolchildren.

Karidas Tshintsholo

Co-founder and CEO, Khula!

South Africa

Khula! was built on friendship.

“We [Matthew Piper, Chief Product Officer and co-founder] became friends pretty quickly at university,” Karidas Tshintsholo, wearing a powder blue suit and a bright smile, says to FORBES AFRICA.

“And then the friendship grew into business. I think already by the second semester of our first year [in university], we had an education type of business running.”

It was after university that Piper returned to Johannesburg with ideas that he relayed to Tshintsholo.

“Initially, agriculture is not a very sexy industry,” Tshintsholo laughs. “From the outside, it looks pretty dirty and all of that…Almost everybody on the continent is dependent on agriculture for survival. But it just didn’t make sense that we were getting more food in than what we were taking out. We should be ideally positioned to be supplying the world 10 times over.”

And with that in mind, Tshintsholo, Piper and Jackson Dyora (Chief Technology Officer and co-founder cofounder) set out to build Khula!

In a nutshell, the company provides small-scale and commercial size farmers with software and a marketplace to grow their business. The whole idea was to be an ecosystem of support to farmers across Africa. The platform has three key components: an input marketplace, which allows farmers to purchase inputs and get technical services; there is a trader platform where farmers can sell; and to close the loop, there is a funded dashboard, where the platform links farmers with financing assistance.

“I think it really speaks to the nature of agriculture,” Tshintsholo says, “that quite often, when you’re trying to solve one problem, you get undone by another problem.” This was what drove him to entrepreneurship to begin with–wanting to solve problems.

“I think Mike Tyson said ‘everybody has a plan until they get punched in the face’. And I think entrepreneurship is like that…We went into this thinking, we’ve got this, and we have a solid plan, we are going to connect farmers with buyers’. Easy. Until…”

“How many times have you been punched in the face?” we ask. “I get punched in the face every day,” Tshintsholo laughs. “We had to get a lot of punches. But I think the pilot helped us because the farmers were okay with giving us those punches, because in the end, we’re working together to build a product that we can then begin to scale.”

Loading...