Riding through its past grandeur, this writer photographed several monumental buildings but missed the city as it appears in old wood prints and paintings.

Leaving Dakar, Senegal’s capital and largest city, by taxi, I was excited to visit the World Heritage City of Saint-Louis four hours away. The city sits on an island at the mouth of the Senegal River. By 1817, it became

the administrative center of the colony of Senegal thus becoming the focal point of French commercial and political activities in the region, gradually built up with military buildings and public and religious institutions such as hospitals, schools and a cathedral. In 1895, it became the capital of the four initial territorial colonies of French West Africa.

Today, Senegal is one of the most stable electoral democracies in Africa that has also undergone two peaceful transfers of power since 2000.

I had come to Senegal during its national elections and reported about it in this magazine in 2019. On that trip, I had visited the slave trade island of Gorée, which was active until 1848, just outside of Dakar, and also Saint-Louis, giving me an opportunity to see two different sides of French colonial governance.

Loading...

Arriving on a very hot day, I chose a horse and buggy ride to slowly meander through the streets and the waterfront of the once magnificent city.

UNESCO had designated it a World Heritage City citing its importance for “exhibiting its influence on the development of education, culture, architecture, craftsmanship and services in West Africa”.

By the late 18th century, history says it had grown into an important commercial hub of the trade in enslaved captives.

Crucial to the conduct of trade and the running of the island were the group of women called signares, many of whom were married to French or British traders and their descendants, who came to be called habitants.

As the slave trade was replaced by the trading of gum and groundnuts, the habitants managed to position themselves as middlemen between the hinterland production and French traders.

Habitants had participated in the partial governance of the colony, with the first habitant mayor of Saint-Louis elected in 1778. However, history was made in 1914 when the first African, Blaise Diagne, won a seat in the French National Assembly.

By 1946, all the African colonial subjects of Senegal gained voting rights previously reserved for the habitants.

However, after 1957, when the country became independent and the island of Saint-Louis lost its privileged capital position to Dakar, it lost its French population and the military departed, diminishing its capability to maintain the historic buildings in the absence of a robust economy.

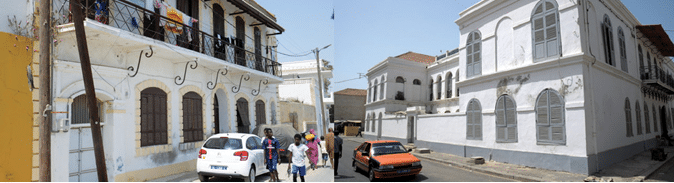

Riding through its past grandeur on my trip, I photographed several monumental buildings, including the Governor’s palace, the Cathedral and many of the crumbling French colonial villas from the 19th century. Despite funding from UNESCO, I personally observed a lack of effort to restore this beautiful city.

Corruption, I was told, was diluting the funds available for that purpose.

Crossing the famous over 1,000ft-long Faidherbe iron bridge (opened in 1897) to the African mainland, I visited a local establishment to taste a native meal – the Yassa poulet-Senegalese- braised chicken with caramelized onions.

While very pleased to have visited this historic city, I left with an empty feeling that it is far from how it appears in old wood prints and paintings. Like the many colonial cities I have visited in Africa and Asia, population increase, poverty and a reported anti-colonial bent slowly seem to be dissolving these places into oblivion.

Loading...