Olushola Medupin wanted to stay away from the food business but now has a growing array of upscale restaurants selling West African cuisine in some of the world’s most dazzling cities.

For Olushola Medupin, his passion for food was a gift passed down generations, like a prized heir- loom. His mother ran one of the most successful restaurants in Kwara State in Western Nigeria, and before her, his grandparents too ran their own local outlets selling inexpensive, pre-cooked food to hungry customers.

Cooking, literally, is in his blood. “My mother was in the restaurant, cooking, when she had to rush to the hospital to give birth to me,” says Medupin. “The only life I knew from a young age was to go to school and from there, the driver would bring me to the restaurant because there was nobody at home. I was forced to stay in the restaurant all day.” That was his world growing up.

Food was such an integral part of the family dynamics that all five children competed as cooks and Medupin always won. From the tender age of five, he knew his way around the kitchen, mastering local dishes such as jollof rice, eba (made from dried cassava flakes) and pounded yam.

In addition to his natural affinity for the culinary arts, Medupin also discovered he had a passion for making money. In 1991, when his father traveled to India for six months and forgot to leave his cheque book at home, Medupin’s mother struggled to make ends meet. He helped by climbing orange trees and selling the fruit in the market. By the time he was 14, he was already a serial entrepreneur, renting out his BMX bicycle for transportation in the local markets, managing a rub- bish collection business, an internet business, a supermarket and a phone repair business.

Loading...

His final venture before he left Nigeria for the United Kingdom (U.K.) was a car wash business which he sold in two months for three times the capital he invested. Medupin used the proceeds to fund his education in the U.K. where he stud- ied investment banking and securities. But he didn’t land the right opportunities.

“I wasn’t getting any major jobs apart from kitchen jobs in the U.K. In 2009, I said to myself ‘I am not working in the kitchen anymore’ and started a security job in Cardiff.”

But very soon, Medupin resigned and started looking every- where else for inspiration. He didn’t want to return into the restaurant business as he had done it all his life.

“It is a very hard industry to be in. You go through a lot of emotional trauma because you must put your heart and soul in the business. If people are not happy with the food, they tell you off straight away and when they do that, it gets to you. So, I didn’t want to do it again,” says Medupin.

The National Restaurant Association in the United States (U.S.) estimates a 20% success rate for all restaurants; but about 60% of all restaurants fail in their first year of operation, and 80% within five years of opening. As much as Medupin fought the idea of starting a restaurant, that was the only viable option before him. He finally decided to give in. He moved back to London, found a place for rent in Lewisham and started his first outlet. It was tough.

“In my first year, I wanted to sell the business. The guy who wanted to buy it from me offered me £300,000 ($375,400) and at the last minute, offered me £150,000 ($188,000) to still run it. It was a struggle initially, but we decided to push through,” says Medupin.

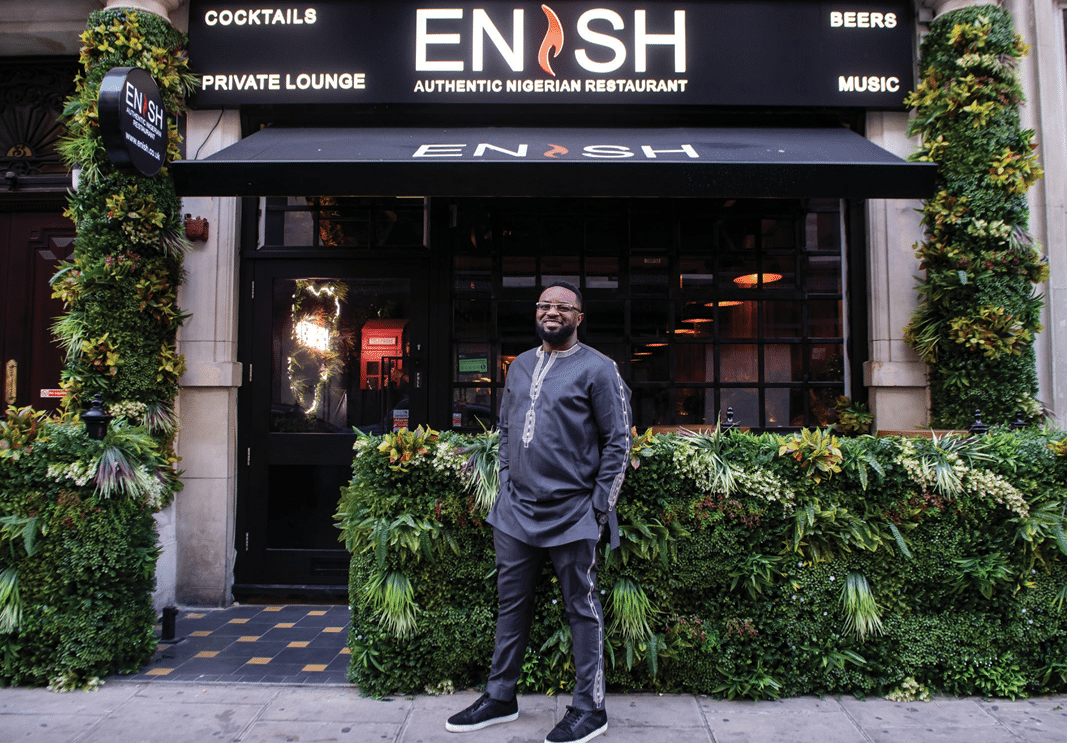

And he made it work. Along with his wife Eniola, also his co-founder, Medupin is today a certified restaurateur with 13 fine dining restaurants, branded Enish, spread across London, the U.S. and Dubai.

West African cuisine has its loyal patrons in London, evidenced by the popularity of Nigerian restaurants such as

Akoko and Chishuru that earned Michelin stars recently. “Not only are African restaurants abroad scarce but also finding the ingredients to cook the food you grew up with can be very challenging in London and America. That is why Enish has such a strong fanbase. They are bringing quality Nigerian food to immigrants abroad,” says Michael Amusan, a financial analyst in London and frequent visitor at Enish Covent Garden.

Concurs London food critic Tola Ogun: “This shows you that West African food, especially Nigerian, is here to stay. Michelin stars were typically awarded to white-skewing restaurants and so for Nigerian restaurants to receive the highest honor in the food business is testament to how popular our food is.”

“For someone like me who is based in the U.K., this is amaz- ing. Nigerian cuisine is growing in popularity all over the world and I am definitely a big fan of Enish,” attests Florence Otedola, popularly known as DJ Cuppy.

Serving everything from pounded yam to egusi soup (made from ground melon seeds) with a side of lobster, Enish has managed to carve out a place for itself in the U.K.’s fine dining scene, and now also in Dubai, where there are multiple outlets.

“The management already knew our brand, so it made it easy to sell our concept. It cost us $4 million to open our first branch and during that year of building the restaurant, we still had to pay a monthly rent of $50,000,” says Medupin. He has invested a lot in each of these projects, such as spending £25,000 ($31,200) a month to rent the dining space on Oxford Street and £20,000 ($25,000) a month for the Knightsbridge location in London, he adds.

In Dubai, known as The Dwntwn By Enish and located near the Burj Khalifa, the world’s tallest tower, Medupin’s outlet is a swanky 40,000sqft nightclub featuring two bars and several VIP lounge areas.

All the way from Africa to the Middle East, Medupin says he imports about 80% of all his ingredients, which presents its own unique challenges.

“You cannot buy egusi for six months at a time and there is an issue with the consistency of the products. Every time you order egusi or palm oil, it has a different taste. So, it’s up to you to use your experience to keep the taste consistent. So, it’s a big challenge,” says Medupin. But he is powering on with his vision to put Nigerian cui- sine firmly on the world map, one dish and one restaurant at a time.

Loading...