An exhibition of contemporary African photography is on at the Tate Modern in London. This writer left not with a sense of a completed narrative, but with a feeling of energized possibility, and the rush of discovering fresh, reconfigured horizons.

How to find the common in the uncommon, the unifying oneness in a disparate whole? Can Africa’s thousands of cultures and languages ever be distilled into a comprehensible photographic representation of an entire continent’s creative impulse? This is the challenge courageously and pugnaciously accepted by the exhibition A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography running through to January 2024 at the Tate Modern gallery in London.

“African photography is recognizable, to those aware of the history of studio portraiture, or of the way Africa is portrayed in documentary photography,” says the exhibition’s curator, Osei Bonsu. “But I was interested in all of the ways in which artists, particularly over the last 10 to 15 years, had completely blown open the perception of what African photography might be; ways that challenged and confounded many of those assumptions about the relationship between photography and the continent. So it was less about this idea of an overarching survey, as this slightly amorphous and impossible-to-define area of activity, and more about locating multiple perspectives that would come together to illuminate some of the key topics and ideas that these artists are engaged with.”

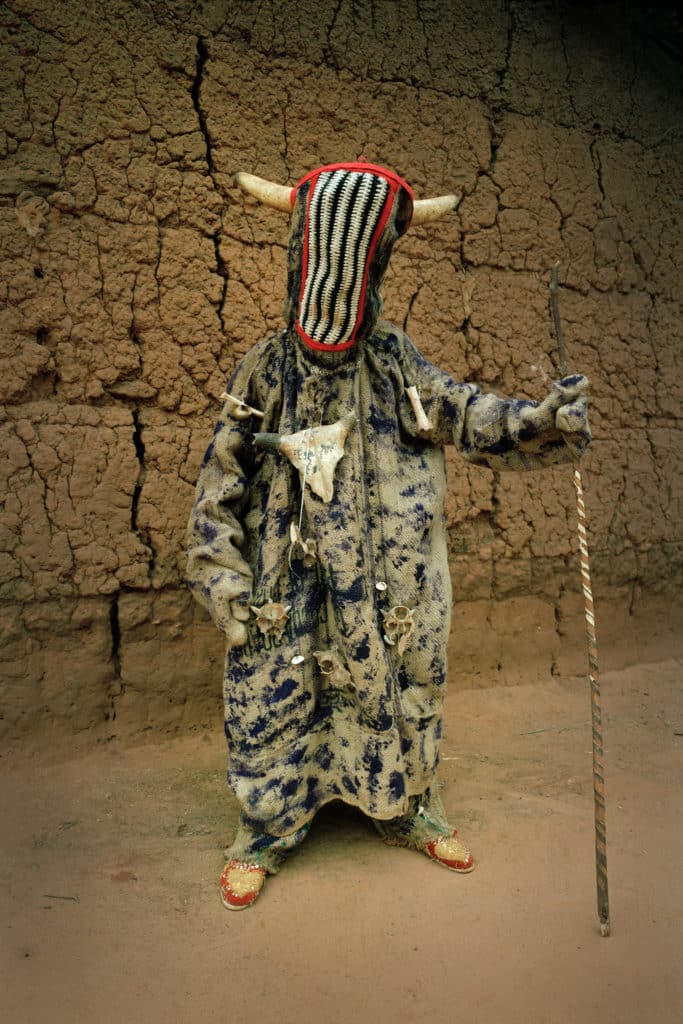

The result is a dizzying whistle-stop tour across three thematic territories: Identity and Tradition, Counter Histories, and Imagined Futures. The viewer is thus drawn and signposted through the exhibition aboard imaginative platforms, rather than the formal conventions of a linear retrospective, in a sort of taster menu of African inspiration: Hassan Hajjaj’s kinetic fusions of fashion photography and the roadside kiosk; Leonce Raphael Agbodjélou’s arrestingly charismatic portraits of quasi-monstrous Yoruba ‘Egungun’ costumes; Mário Macilau’s monochrome double-takes on the horrors of photojournalism; the serenely melodramatic staging of Maïmouna Guerresi’s scenes of prosaic ritual. The exhibition closes with an immersive video installation by Julianknxx, featuring a hypnotic, thrumming dance sequence, shot like a communiqué from a viridescent African Atlantis.

A consistent identifiable dichotomy arose during the exhibition’s research phase, between the commercial bread and butter of the photographers’ everyday practice and the more experimental work they had developed.

Loading...

“These artists embraced photography in ways that undermine or question some of the colonial or exoticizing assumptions around the relationship between African peoples and the photographic medium. This ‘B-roll’, the flip side of what they were doing, was much more subversive than their commercial work,” Bonsu says.

“And what that revealed is that this idea of the split between the conceptual and the documentary is an arbitrary one.” There is an implicit provocation to the audience embedded in this confident, confrontational demand for the artists’ output to be apprehended on its own terms; much of the work playfully exploits a thrilling tension between an observer’s expectations and the creative authenticity of the photographer’s vision.

Bonsu says that the exhibition has benefited greatly from the evolution of the medium and its new plasticity; work can not only be sourced from all over the continent and the diaspora, but also be presented in formats that blur and expand photography’s traditional framings. “I think this has liberated contemporary photographers from many of the limiting structures that we know

many African artists face, whether it be lack of government infrastructure, or lack of mobility,” he says. “Those reductive estimations that Africa wasn’t a space of invention, of intellectual and cultural innovation, are of course a myth.

And it’s a myth that serves much of the colonial history that the exhibition also deals with.” To that end, the show shifts the audience’s perspective through a range of vantage points, media and scales, though there is perhaps an opportunity missed to fill one of the Tate’s gigantic spaces with the kind of colossal image its ambition deserves – an outsized encounter with the teetering sublime of Africa’s infinite complexity might have served as an emotional approximation of the overwhelming vastness of its subject.

There is still much to admire about this exciting, expansive exhibition, with its democratic embrace of both the vibrantly aesthetic and the viscerally provoking. “There are histories of struggle and resistance that are ever present,” Bonsu says.

“But there are also the histories of difference that exist within the fabric of how cultures communicate: through language, through images. That notion of ‘in-betweenness’ is not so much physical, but the psychological in-betweenness that many African diasporic communities can relate to. It’s quite particular to a history of colonial violence, bound up in a deep knowing of one’s heritage, but also this desire to move forward. The exhibition doesn’t try to glaze over the realities that undergird these contemporary histories. The story is still unfolding, and we tried to really embrace that. It’s a challenge for our audiences to really go on that journey with us. They’re not going to have a conclusive sense of a kind of beginning and ending.”

Thus you leave the exhibition not with a sense of a completed narrative, but with a feeling of energized possibility, the rush of discovering fresh, reconfigured horizons.

“It’s that positivity, weighted with this idea of agency – many of the artists are almost suggesting that changing the world isn’t entirely out of reach, that photography itself, at some level, has the possibility to reach into the realm of the imagination,” Bonsu says. “And in doing so, maybe that liberates us – as viewers, as audiences – to think differently about the world we experience.”

Loading...