From bean to brew, Coffee in Tanzania is starting to reveal the hidden world of plant communication.

Picture a coffee bean and you’ll probably think back to the bag you picked up from the artisanal shop to grind at home. You’ll tell your friends or colleagues that these beans are a special blend from some free-trade plantation in Rwanda, Ethiopia or Uganda. You may even show off your connected coffee machine that turns on with an app and knows exactly how you like your next cup brewed. It’s incredibly smart, but what you may not realize is that technology has become an intrinsic part of the coffee life cycle, from farm to Frappuccino.

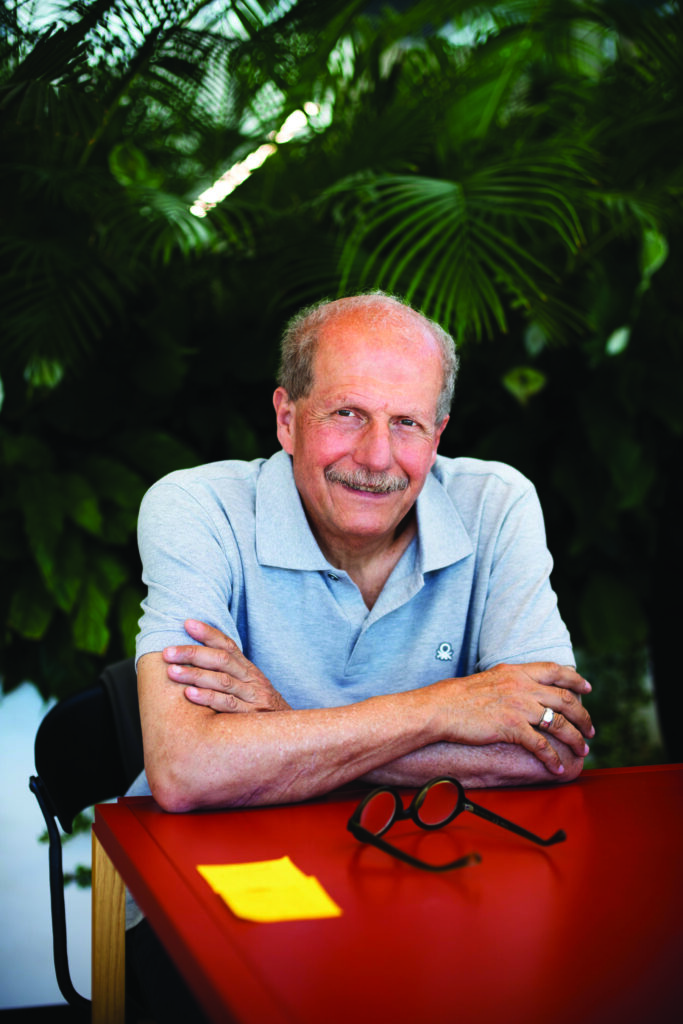

“As a crop, coffee covers 10 million hectares of land. There are over 125 million farmers involved in coffee production,” says Massimo Battaglia, a tropical agronomist and Coffee Research Leader at Accademia del Caffè Espresso in Italy. “And that’s just the farmers, there are also traders, baristas, roasters… the population that is connect- ed to coffee is amazing.”

Coffee is produced in about 70 countries worldwide, but for 12 nations—including four in Africa—it represents their primary agricultural export. This massive industry now faces serious challenges. Unpredictable weather patterns and temperature shifts are threatening not just coffee yields and quality, but the livelihoods of millions of farmers who depend on coffee cultivation.

“Climate change is a reality,” says Battaglia, adding that another issue is the distance between the origin and consumption. Unlike vineyards, which are in good proximity to their end product–it’s possible to drink a glass of wine while looking at a valley of vines–coffee has a geographical issue. “You have to imagine the plantation. But if we can make a wedding between the biology and consumption, I think we can improve the overall value chain of coffee,” he says. “It’s my dream for this technology to help families have a better standard of living.”

Loading...

Sensors and gatherers

To understand exactly how the environment is changing, you need big data. One of the ways to do this in an agricultural environment is to use Internet of Things (IoT) sensors. Cisco has partnered with the ConSenso Project, a coalition of Tanzanian espresso farmers and Italian plant and technology (PNAT) researchers, to fit 65 solar-powered IoT sensors on the Tunasikia Farm in Utengule, Tanzania. Angelo Fienga, Cisco’s Director of Sustainable Solutions for Europe, Middle East, and Africa (EMEA), explains that collecting data in a city, for example, where everything is connected, is easy. But on a farm, the challenge is not only gathering data–the type of data you need is completely different. In addition to this, the information is often spread across a large, open environment. You need a solution that doesn’t involve planting dozens of disruptive antennae in addition to your crops. And once this data is captured, it has to be both managed and secured.

“You have to protect the data coming from the field,” says Fienga. (LoRaWAN, Cisco’s long-distance, low-power consumption radio-transmission technology, is one of the key solutions helping to connect Tunasikia sensors.) Camilla Pandolfi, CEO and R&D Manager at PNAT, a think tank of biologists, designers, and social and environmental scientists in Italy, explains how these sensors can capture data on soil, sun, climate, carbon capture, insects, and–most interestingly–the plants’ electrical energy fields. “We know we will be able to monitor not only water needs but also pathogen attacks, nutrient needs so we can really improve the sustainability of consumption by helping farmers to perform treatments at the right time,” she says.

“We’re really monitoring what the plants are doing by inserting electrodes that monitor electrical activity. It’s like performing electroencephalograms on plants.” These electrodes detect the subtle electrical signals that flow through the coffee plants, revealing a hidden world of plant communication. The sensors across the farm take measurements every five minutes. This creates a detailed picture of not just the environment, but also how the coffee plants respond to it. “What we are measuring is something very delicate,” Pandolfi adds. “Even if you touch the plant, you introduce a sort of perturbation of the signal.”

Listen up

Of course, building technology that can survive in Tanzania’s coffee fields was no small challenge. The sensors needed to be waterproof, self-powered and small enough to attach to plant stems without causing damage. “We had to trade-off between the amount of data we wanted to acquire and the electricity we had available,” says Pandolfi. PNAT’s solution was to create compact devices with solar panels that can operate for up to a week without sunlight. Early results are promising–the researchers have found clear relationships between water availability and changes in the plants’ electrical behavior and these insights are turning traditional coffee agriculture on its head. “Normally, I fight with my father about his old farming ideas,” laughs Battaglia.

“But in this case, it’s upside down–we ask the plant what it needs. It’s the plant that helps us find the solution.” As Fienga puts it: “The technology is making the plant talk to the cloud. You’re giving a voice to the plants to tell us ‘I’m thirsty’ or ‘I’m sick’.” For coffee growers facing increasingly unpredictable rainfall patterns, direct communication with their crops could be transformative.

The PNAT team believes this approach will eventually allow them to detect not just water needs but also disease outbreaks and nutrient deficiencies through electrical signals alone. “We can really improve sustainability by helping farmers perform treatments at exactly the right time,” says Pandolfi. For coffee, which requires more than 2,000mm of rainfall annually, understanding precisely when plants need water could help farmers maintain yields even as climate conditions become more challenging. “This is a revolution in agriculture,” says Battaglia. “You don’t impose anything but instead listen to the plant to find the right decision at the right moment.”

Loading...