As FRELIMO’s candidate takes office under tight security and allegations of electoral fraud, opposition boycotts, youth-led protests, and mounting socioeconomic pressures reflect a nation at a crossroads.

Yesterday’s inauguration ceremony in Maputo marked a pivotal moment in Mozambique’s fraught political landscape, as Daniel Chapo assumed the Presidency amid allegations of electoral fraud and heavy security measures.

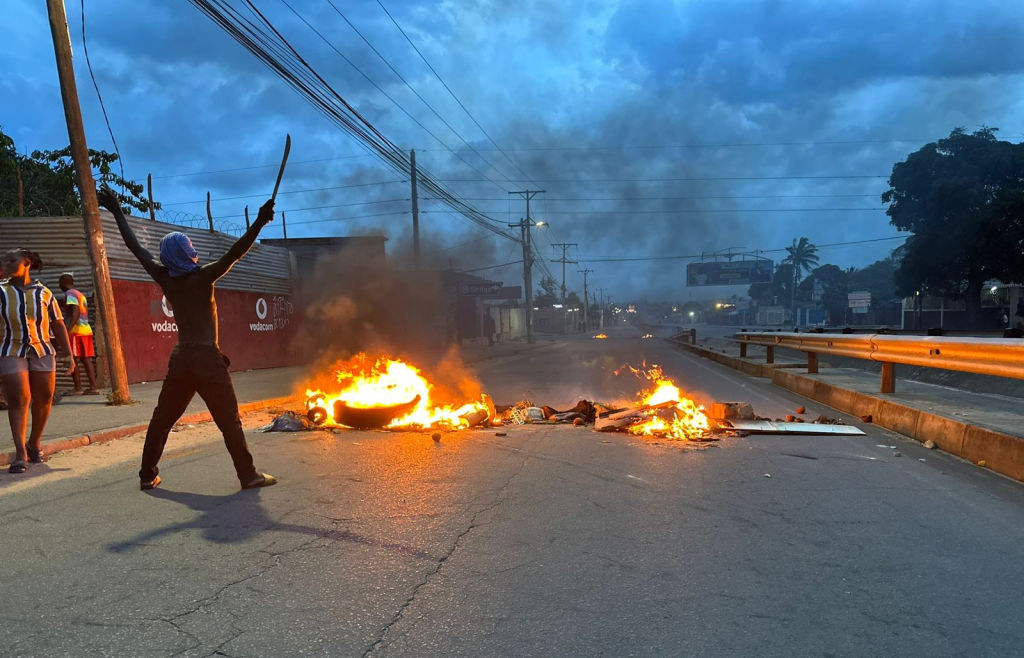

The Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) faced intense scrutiny following reports of ballot-tampering and intimidation in last year’s election. At least eight people were reportedly killed by security forces during protests surrounding the inauguration, while a local civil society group has said more than 300 people have been killed in clashes with security forces since October.

Chapo’s ascent to power continues despite months of legal challenges and widespread public outrage. According to independent political analyst Marisa Lourenço in an interview with FORBES AFRICA, institutional domination by FRELIMO left opponents little room to maneuver once the official results were certified.

“FRELIMO controls the Electoral Commission and the courts,” she says, adding, “so there aren’t any other legal or formal avenues to continue to challenge the results.”

Loading...

A Bloody Backdrop to a Presidential Inauguration

Chapo’s inauguration took place under tight security in Maputo’s Independence Square, following general elections held on October 9, 2024. Observers, both local and international, raised alarms over alleged irregularities in the voting process.

Opposition parties, including the Mozambican National Resistance (RENAMO) and the Democratic Movement of Mozambique (MDM), boycotted the ceremony, while upstart party, Podemos chose a more qualified acceptance by taking parliamentary seats.

Public sentiment has been notably tense, with many citizens accusing FRELIMO of corruption and authoritarian methods.

Background on the 2024 General Elections

The stakes were high when the country went to the polls, given Mozambique’s economic challenges and FRELIMO’s decades in power. RENAMO brought its own legacy of conflict with FRELIMO, while MDM sought to bolster its influence. Podemos emerged as a fresh alternative for many voters.

Independent candidate Venâncio Mondlane claimed a majority of votes, labeling the official results a “theft of the people’s will”.

Complaints, tampering and intimidation characterized the post-election landscape. The Constitutional Court introduced minor adjustments to Chapo’s vote share and reallocated a few parliamentary seats but did not address deeper systemic grievances.

Opposition Reaction and Legal Recourse

Mondlane’s insistence that he won—bolstered by viral social media videos—added to the nationwide protests, which escalated after his lawyer was killed under suspicious circumstances. RENAMO and MDM announced boycotts of parliament, citing what they viewed as blatant electoral fraud. However, the promise of parliamentary influence and financial benefits prompted Podemos to accept its seats on January 13.

“They have more money and power to gain in accepting the situation than if they continue to oppose it,” observes Lourenço.

The Constitutional Court’s validation of the results effectively closed any formal channels for renewed litigation.

Efforts to Rebuild Trust

Though Chapo’s final tally was marginally reduced, many citizens saw it as a superficial measure that failed to dispel deep-rooted skepticism.

Furthermore, high unemployment and pervasive corruption has disproportionately affected younger Mozambicans, who have played a visible role in recent protests. Many reject FRELIMO’s liberation-era credentials.

“They also tired very quickly of main opposition RENAMO and were key to the success of Podemos,” says Lourenço, illustrating the generational shift.

Calls for job creation and anti-corruption measures have intensified, and observers have reportedly warned of potential radicalization if grievances remain unanswered.

Government Response and Long-Term Implications

Chapo’s presidency so far suggests FRELIMO will prioritize stability and security control. Human rights advocates have also condemned the use of live ammunition on protesters.

“FRELIMO under former president Filipe Nyusi has become much more draconian, and so is likely to continue to clamp down on dissent,” Lourenço states.

Rising inflation, frequent public-sector strikes, and a potential exodus of skilled workers loom large. FRELIMO’s closer ties to authoritarian governments could further strain relations with democratic neighbors and investors.

“This election has been a turning point,” Lourenço comments. “It has shown just how far FRELIMO will go to protect itself.”

Civic organizations also continue to demand electoral reforms, media freedoms, and more decisive anti-corruption measures.

“Mozambique’s political future looks fraught with clashes between a rigid ruling party and a largely disillusioned population,” says Lourenço.

“While immediate post-inauguration tensions might recede, the deeper issues—corruption, inequality, youth disenfranchisement—will keep re-emerging until they’re adequately addressed.”

Loading...