Besides white, perhaps the only other color that gets mentioned in Orania is orange.

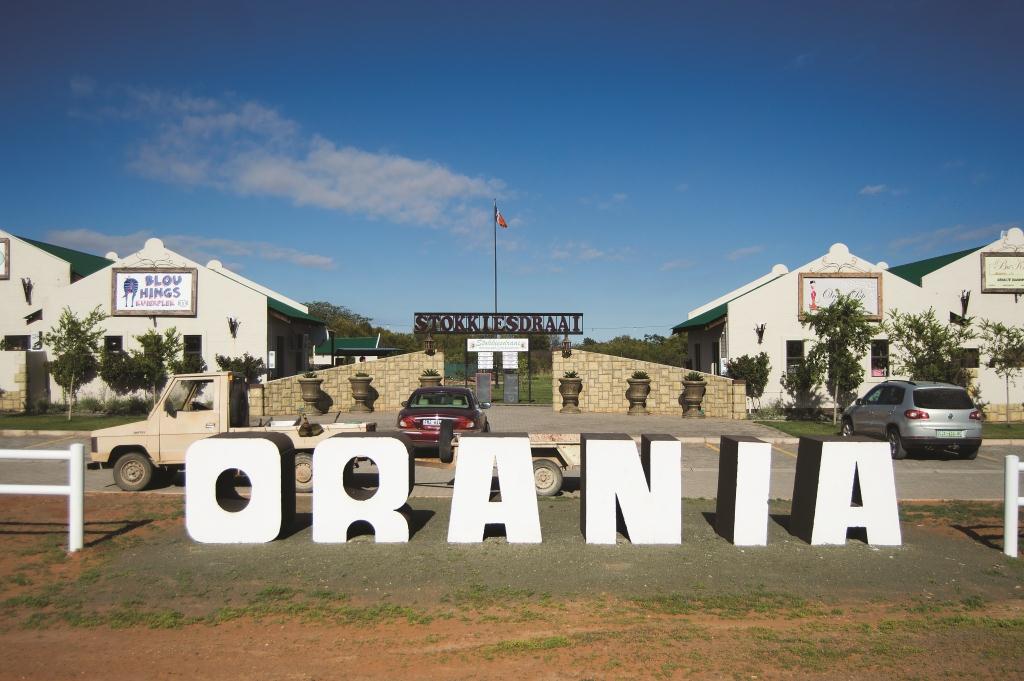

Orania, a whites-only town flanked by the majestic and breathtaking Orange River, is about 160 kilometers outside Kimberly in South Africa’s Northern Cape province.

South Africa may have entered its 23rd year of democracy, yet this Afrikaner town has no desire whatsoever to be a part of the ‘Rainbow Nation’.

Orania is secluded, separated and solo.

And so on a sunny Tuesday morning, I drive to Orania with my colleague from Soweto, photojournalist Motlabana Monnakgotla. Like him, I am black South African, from Harrismith in the Free State.

Loading...

Who knew we would one day pull up into the streets of this arid town?

A rusty signboard greets us about 10 kilometers before Orania. We approach with trepidation, not knowing what to expect from South Africa’s only town with no black residents.

There are no walls, security or gates preceding Orania. No grim militarized borders – a la Donald Trump’s proposed Mexico wall – so now that’s a big relief.

Instead, next to a grocery store and the town’s petrol station is a wall rife with color, a festive reminder to the locals of the fun fair taking place later in the year.

– Carel Boshoff (junior)

Our contact is Orania’s Communications and Marketing Director James Kemp, who has agreed to meet us at this location.

The desolate gas station has two dusty petrol tanks; a young white attendant waits idly for the next customer.

While we wait for Kemp in our rented car, some of the locals stare at us, making us aware we are quite conspicuous.

Kemp arrives in a white Mercedes-Benz, and we follow him to a restaurant in a resort located in a leafy part of Orania. As we drive up, the locals we pass wave at us. Their welcome comes as a surprise.

The resort is Aan-die-Oewer, Afrikaans for ‘On-The-Banks’ – situated on the banks of the Orange River. Kemp tells us the area attracts holiday-goers and families through the year because of activities like bird-watching and fishing.

According to the information compiled in Orania’s tourism booklet, the town attracts almost 30,000 visitors annually. An increasing interest in Orania has helped the tourism sector and businesses such as guesthouses, restaurants and a spa have since opened.

We receive a warm welcome at the restaurant and I marvel at the captivating beauty of the Orange River, the largest river in the country.

Even though this self-styled 8,000-hectare enclave is isolated from the rest of South Africa, the community of Orania denies they live in remoteness.

Instead, they say they have chosen to embrace the community made up of Afrikaners only, in order to remain true to Afrikaans’ tradition and culture.

Dr Sonwabile Mnwana, a sociologist and Deputy Director and Senior Researcher at the Society, Work and Development Institute (SWOP) at the University of the Witwatersrand explains Orania was established after Afrikaners felt threatened by issues such as poverty in urban areas and political defeat in the wake of a liberated South Africa.

In order to understand why a community like Orania came into being, Professor Kwandiwe Kondlo, a professor in Political Economy at the University of Johannesburg, says the political and historical context of South Africa needs to be taken into consideration.

In the 1990s, when the idea of a new government was taking shape, Kondlo says negotiations for national liberation were compromised.

“We had a situation in South Africa where the oppressor and the oppressed were declared both victors at the negotiation table, and that never works in the long run. The liberation movement [African National Congress] negotiated with its back against the wall,” he says.

– Annelize Kruger

The outcome of these negotiations was the country’s first democratic elections. And the elections saw a black president, Nelson Mandela, elected for the first time and a black-run government, the African National Congress (ANC), helm the country.

The 1994 elections had been long overdue. In 1989, the former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher wrote a firm one-paragraph telegram to then South African President F.W de Klerk to provide a date for Mandela’s release from prison. The White House supported this request and pressure mounted on the Afrikaans leadership to free Mandela.

“On the 10th February, 1990, F.W de Klerk announced in Parliament that on the 11th February, 1990, Nelson Mandela will be released from prison. This announcement came as a surprise to everyone. Not even his friends in cabinet knew about it. The ANC likes to boast about many things… the old man [Mandela] could have died in prison if the Boers were not put under pressure,” says Kondlo.

Economists like Kondlo call the 1990s the New Phase of Financial Globalization, which pushed for a borderless world. However, after 2015, the global political economy started shifting again.

He says that is why, for example, Americans voted for President Trump, as a way of “applying brakes to the wave of globalization”.

A security valve

Orania was established in those turbulent years, in the early 1990s, when South Africa was pushing for unity with every race in the country.

“Orania is a security valve for Afrikaners in a negotiated democracy,” says Kondlo.

However, the notion of separatism and self-determination that Orania has been famously documented for isn’t unusual.

Dr Frans Cronjé, CEO of the Institute of Race Relations (IRR), says people that have actually “exited South Africa” and decided to live in seclusion, are those who live on golf estates and private housing establishments and not just in Orania.

“Even though in Orania, there is just over a thousand people, hundreds of thousands of South Africans have actually made the same decision of going to live in relative seclusion,” he says.

According to Kemp, anyone can move and live in Orania, provided they can fully adopt and express the Afrikaans culture and way of living.

Max du Preez is a veteran Afrikaans journalist and columnist who, in the apartheid years, founded Vrye Weekblad, an Afrikaans-language weekly and the first anti-apartheid Afrikaans newspaper.

“Orania is practicing separatism because they are motivated by fear of being swamped by the majority black society, fear that they may lose their language and culture, and fear of crime. Most Afrikaners don’t share their fears to the same extent. I cannot see modern, urban and professional Afrikaners ever feeling at home in Orania,” notes Du Preez.

However, Kondlo says the elite Afrikaners could “surprise everyone” and move to Orania if the South African government collapses in the years to come.

In the 1980s, the founder of Orania, Professor Carel Boshoff, was chairman of the Afrikaner-Broederbond, a movement known to be the Afrikaner think-tank.

An entrepreneur shows the Oranian currency, Ora

“The Afrikaners are very forward-thinking people. Orania was established as a tactical strategic exit for the Afrikaner, should the new South Africa run into serious crisis. They will then have a place to preserve themselves,” says Kondlo.

In 1991, as the country headed towards a democracy, which Archbishop Desmond Tutu referred to as the Rainbow Nation, a group of 40 Afrikaner families led by Boshoff proceeded to start their own state in the Karoo.

Even though it was established in 1991, the land Orania sits on was initially built in 1963 by the Department of Water Affairs and known as Vluytjeskraal, referring to the place where the town was established. Colored workers lived there, whilst working on building irrigation canals connected to the Vanderkloof Dam.

As the wheels of change started to roll, Boshoff, who is former South African Prime Minister Dr Hendrik Verwoerd’s son-in-law, bought the abandoned 500-hectare land, which has since expanded to 8,000 hectares, for R1.5 million (approx. $521,000 at the time).

He envisioned tens of thousands of people occupying it, yet today, 26 years later, Orania is home to only about 1,300 residents.

Cronjé says this low number shows there isn’t a high demand for an establishment like Orania amongst other South Africans.

Orania’s annual population growth is reportedly about 10% and over the years, political leaders like Mandela, Jacob Zuma and EFF President Julius Malema have visited the community.

“The ANC is moved by numbers and due to a slow rise in Orania’s population, they [ANC] don’t see them as a threat. But remember, an elephant can be killed by an ant,” says Kondlo.

Whether Orania is a community that only has self-preservation at its core or if it’s indeed an enclave for Afrikaners should South Africa experience crisis, remains a burning question.

Boshoff’s son and the current president of Orania, Carel Boshoff (junior), says his father was attracted to the idea of “a sort-of Commonwealth South Africa” and in the 1970s, he had the impression that the idea of a white minority government was unsustainable.

“He did not see a white minority government being replaced by a black majority government very attractive, because [to him] it was just turning the picture around,” he says.

In 2011, after 10 years of leading the community of Orania, Professor Boshoff died aged 83 from cancer. He is buried next to his mother-in-law, Betsie Verwoerd, in a small cemetery in Orania.

The cemetery has several simple tombstones of people who once lived in Orania. A pointy tower rests atop a round tombstone located at a higher point in the big yard, which serves as a monument for Verwoerd’s late wife, Betsie, and Boshoff.

A stone’s throw away is a decrepit water mill structure used in the 1960s. Overlooking the cemetery is a lush green maize field, giving the brown surroundings verdant appeal.

Volkskool Orania

An intentional community

Agriculture is Orania’s mainstay. The town has over 15,000 pecan nut trees as well as wheat and corn fields.

Self-sufficiency is the norm here. All labor in Orania is undertaken by residents and according to records on Orania’s website, the unemployment rate is under 3%.

“If you are lazy and not willing to work for yourself, you will not survive in Orania,” says Kemp, who lived in Pretoria before moving to Orania three years ago.

The residents do all the work such as building houses, service delivery, plumbing, fixing cars, administrative work at the municipal office, farming, legal matters, healthcare, teaching and construction.

A German who brews craft-beer is the only non-Afrikaner we meet in Orania. He moved here 18 months ago and sells his beer in Orania. Kemp says the beverage has proven to be a favorite among the locals.

A soft-spoken Carel (junior) says Orania carries the concept of an intentional community, which means, as a community they are not only looking back but forward as well.

“When people move to Orania, the important questions we ask are ‘what are your intentions, aspirations and ideas for the future’. I am confident to say – in the broader sense – what my father had in mind when he bought Orania is what is still being done,” he explains.

Be that as it may, Lindsay Maasdorp, national spokesperson of The Black First Land First movement, says he has nothing against people who want to preserve their language and culture, but feels differently about the residents of Orania.

“The people in Orania have the highest form of white arrogance,” he says.

Maasdorp says areas like Orania destroy the idea of the Rainbow Nation and instead, its residents only practice racism.

“The idea that white people can cut themselves off the entire country, may seem like they do not want to interact with black people. It’s a stigma attached to us [black people] and the only way we can break that is to take all the land back including Orania,” he says.

A lingering question is how, in working towards a united South Africa, the right to self-determination and a self-governed community was granted to Orania’s founders. Their support is a clause stipulated in Chapter 14, Section 235 of the Constitution of South Africa.

“[In it], the aspect of national self-determination is referred to in broad terms and does not speak specifically to historically-oppressed groups. This aspect was signed by both sides of leadership and the Afrikaner’s strategy was very calculated. That is why in terms of law and the constitution, it is very difficult to confront Orania,” says Kondlo.

The residents of Orania exude a sense of forced friendliness and appear used to the media attention their lifestyle, beliefs and livelihood attract.

Carel (junior) admits scores of journalists have visited Orania, and from his responses, it’s easy to see he knows his answers well.

“We are not multi-cultural activists, we look at our culture and the idea of the uniqueness of culture in a positive way,” he says.

Du Preez opines Orania is not threatening anyone and the community is not a burden on the state.

“I believe they should be left in peace. They’re not the first ethnic/cultural/language community in the world who wants to withdraw from broader society,” he says.

Municipal workers in a van enroute to work

Orania’s entrepreneurs

Sarel Roets is a minister-turned-businessman who moved to Orania five years ago. He owns several businesses and properties here, including a commercial office park. It is modern and located with a perfect view of the Karoo’s brown and rocky plains.

Most of the infrastructure in Orania is stylish and up-to-date.

Roets grew up in a conservative Afrikaner home and says like most Afrikaners, were “originally pro-apartheid”.

He says Orania has exposed the Afrikaners to a life of self-reliance. Most of them had grown up with domestic workers and gardeners who did all the manual labor in and around their homes.Now they do it all on their own.

“We used black labor everywhere we went and had a black lady doing laundry in the house. That is legalized slavery,” he says.

One of the buildings on Roets’ property is Roelien de Klerk’s jewelry shop. Oranzi Pop sells offbeat jewelry, all handmade by her and her assistant who sits at the back of the store. The shop also sells colorful scarves, bags, sunglasses and small, intricately-carved treasure boxes.

My colleague grabs a pair of small flower-shaped wooden earrings for his 10-year-old sister. I too am tempted to buy something, to serve as a souvenir from Orania, but think twice seeing some of the price-tags.

De Klerk has been living in Orania for over 20 years now and says her dream is to start a jewelry school. She desires to pass on her jewelry-making skills to the next generation since she knows there is a gap for such expertise in South Africa.

A majority of the jewelry in her store gets ‘exported’ into the rest of the country, which has helped grow her business and in a small way, contribute to the town’s economy.

Residents are proactive in making a living for themselves in Orania and the town prides itself in being eco-friendly. Every corner in town has clearly-marked bins with labels of what should be thrown in for recycling. Also, every building in Orania is required to have a solar panel.

This part of the country is dry and the sun is scorching, so around midday, all the laborers drop their tools and head indoors to cool off.

We pass a swimming pool and see a mother and daughter walk out with towels around their waists. In front of the swimming pool is a large monument of a koeksister, a sugary deep-fried treat enjoyed mostly by the Afrikaners.

A street away from the pool is a contemporary white building with wide open wooden doors. A few cars are parked in a spacious parking bay on the side of the building. The building is a hair salon owned by Annelize Kruger.

“Oh I fixed my hair just for you guys,” she gushes as we enter her stylish salon. The burgundy walls are decorated with paintings of flowers and other eye-catching drawings. A petite woman sits behind the high counter, looking on silently with a smile.

Kruger says she moved to Orania from Pretoria three years ago because she could no longer take the traffic in the city.

“In Orania, it takes me five minutes to get to the shops, another five to go home and I would still have another 45 minutes to relax before coming back to work,” she says.

Kruger is bubbly and friendly. She says her hair salon is one of many in Orania, and in order to stay ahead, will be opening her own hair academy.

“In Orania, you need to do more than one thing in order to sustain yourself. I asked the Lord what else I can do here and He said I should use what I have. It has been a faith process,” she says.

Kruger says students can come from anywhere in the country. They would have to apply first and then come for interviews before training.

So far, she has one student and says she gets accreditation from the Quality Council for Trades and Occupations for the training.

Kruger willingly smiles for the camera and agrees to pose for the several angles my colleague suggests.

“You can come here all the way from Johannesburg and I can do your hair!” she jokes with me as we leave.

Orania also has its own currency, the Ora. According to Orania’s website, Die Orania Beweging, the Ora has been used since 2004 and was created to promote local spending. It operates like a coupon system whereby, if used to purchase goods in the town, residents are given discounts on their purchases. The value of 1 Ora is equal to R1.

The community uses the Ora to keep their own cash in circulation, while their rands are placed in banks and accumulate interest.

“Since we don’t get funding from the government, we have international partners – called Friends of Orania – who help us with funding. Currently, there is R500 million [$37 million] invested in Orania,” he says.

Monument Hill where former Afrikaner leaders’ busts are displayed

On their website, Friends of Orania is a group of people in Europe, working on creating an “autonomous European organization” with the aim of supporting the Afrikaans community.

Orania also has a community radio station, Radio Orania. The studio is located in the town’s municipal building and boasts basic audio equipment. It is accredited with the Independent Communications Authority of South Africa (ICASA) and its frequency stretches to a radius of about 40 kilometers.

Their programs range from community announcements, poetry and Afrikaans folk music. They don’t have frequent news slots or shows on current affairs. The town also has its own community magazine, Voorgrond.

A 10-minute drive from the radio station takes us to Monument Hill. Here, bust-statues of former Afrikaner leaders look down on the parched town.

Paul Kruger, JBM Hertzog, Verwoerd, DF Malan and JG Strijdom encircle the town’s totem, ‘Die Klein Reus’, Afrikaans for ‘The Little Giant’. It’s a statue of a young boy rolling up his sleeves, demonstrating his readiness to work.

Even though the original artwork of the boy was made by German-born South African artist Elly Holm and given to Verwoerd as a gift, the leaders of Orania have since made this piece of art their icon. Carel (junior) says the busts represent their heroes and choosing to keep them was the obvious thing to do.

“We can’t look at those leaders from the early stages and allow their busts to get buried under dust in store rooms. We need to be true about where we come from as well. It’s not to say they never made mistakes but we are owning up to our history – bad and good. We don’t believe it was only bad,” he says.

In 1948, the National Party governed South Africa led by Verwoerd and because of his role in implementing the apartheid policies in the country, he is mostly called the ‘Architect of Apartheid’.

In a central part of Orania is Betsie Verwoerd’s house, now a museum. Joost Strydom, a Junior Communications Officer at Orania, takes us to it. It looks like any other home, except for Verwoerd’s bust at the front gate that reminds us this is a museum.

Along the pathway leading to the front door, my colleague and I pluck juicy grapes hanging off a steel arch. It feels strange eating from the Verwoerds’ vine.

The museum is filled ceiling to floor with Verwoerd’s pictures, clothing, gifts, collectables and everything else that belonged to him.

In one room, Betsie’s old-fashioned belongings hang from the cupboard knobs and family pictures crowd the small tables in the room.

Atop a doorway leading to the rest of the house, is Verwoerd’s fishing rod. Pictures around the rod show him revelling in his many fishing outings.

His portraits are on small, medium and large canvasses. Small sculptures of him fill almost every corner of the house. His pictures are all framed and one particular image of him is placed in a colorful round-glass bubble.

In one room, in a large glass case, lies the suit he was wearing when he died after being stabbed four times by Parliamentarian Service Officer Dimitri Tsafendas, in September 1966.

Next to the navy-grey suit are things that were in his possession at the time of his death. In a little room next to the glass case, are piles of handmade wooden Basotho, Khoisan and African craft stacked on a counter.

Different kinds of bows and arrows and spears hang on the wall. We are told these were gifts he received from his black counterparts and leaders during his reign.

After 15 minutes at the house, we exit and walk into a warm afternoon.

For a moment, the pleasant weather makes us forget where we were.

Life in Orania

Like the stillness around us, the community of Orania is content. They handle their own affairs and continue building their establishment.

However, internationally, in view of a re-igniting of right-wing populism and changes in the new world order, it can never be clearly known what a community like Orania can grow into, especially if the major state – South Africa – starts facing serious challenges, as Kondlo says.

The advantages that Orania could gain in that respect remain unknown. He avers while the majority of South Africans are pointing fingers at Orania, in hindsight, it is the rest of South Africa that is exposed and vulnerable.

A democratic South Africa could be “a fallacy created to stop bloodshed and apartheid”. Yet, in a place like Orania, it is what could have led to the establishment of “a secured, private enclosure that will shield the minority group in the event of a greater crisis”.

For now, the people of Orania are going about their lives, solo and satisfied.

Loading...