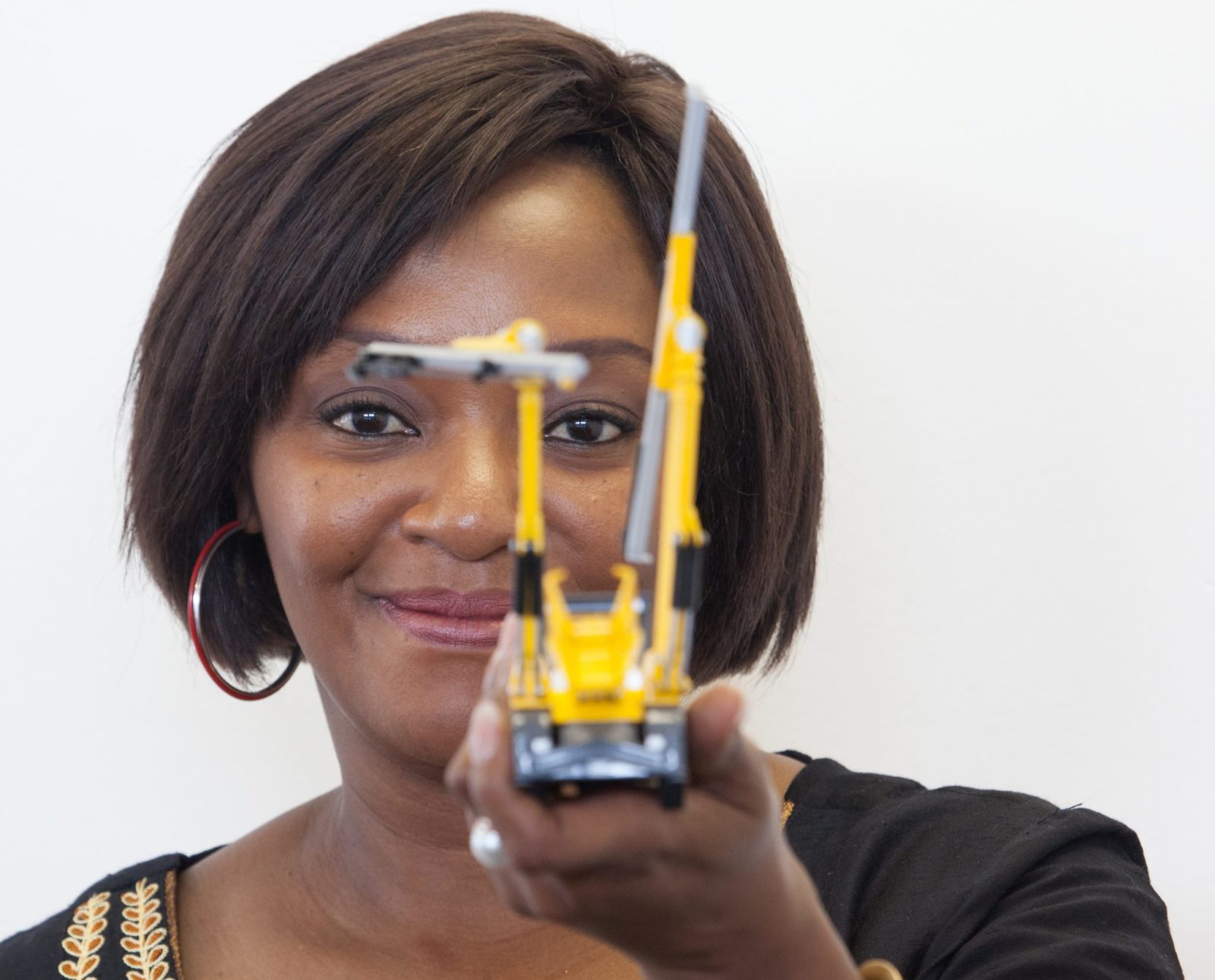

When entrepreneur Maureen Dlamini took over as CEO of the Chamber of Mines of Zambia (CMZ), she had no idea what she was getting into. It’s arguably the toughest job in Zambia; running the lifeblood of the country – copper mining. Dlamini keeps the flow of private investors and government in line. What’s more, until two weeks into the job, she’d never been down a mine.

“It was 14 January, two weeks after I began as CEO, that I had my first taste of the mines. I was in awe. I looked at the size of the machinery and the size of the pit. It gave me a different perspective of the mines. Actually seeing it, I had a greater respect for investors. You really don’t know that you will get the return you anticipated. You are dealing with nature, you could have disasters, you could have flooding. To have enough faith to invest $2 billion when your return is not immediate, is something I learned to respect,” she says in her office in Lusaka.

Copper. It is the industry that died and came back to life. Zambia has been exporting since the 1920s, but it’s been a rollercoaster ride complicated with colonial privatization, nationalization, and then privatization again.

According to the World Bank, Zambia has the largest known reserves of copper in Africa, 6% of the world resource. It means businesses are flocking to Zambia as if it were the days of the 1849 California Gold Rush.

Loading...

For Dlamini, the job in mining is a far cry from what most people expected of her, she says. She worked in finance with the likes of Barclays, First Line of Africa and was the former Executive Head of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange’s (JSE) Africa Board before moving to home, Zambia.

In Lusaka, she went into business with her brother to run Zambezi Airlines, a private airline, but the business failed to take off. Controversially, its operations were shut down by the government citing safety concerns. It went bankrupt in 2012 and Dlamini was thrown out.

“My agent just called me and said there was a job…I said yes I’ll try it.”

This was how Dlamini took the position of CEO of the CMZ; the rest was history. Dlamini even had to put her dreams of becoming an interior decorator on hold to take up the position.

“My real passion is interior decorating. I love event management. From here I could do it and work until 4AM. I would love to be able to do it at some time at my own pace. My friends say to me I love to challenge myself, and maybe that’s why I am in the mining sector,” she says.

Her first step was to Kansanshi mine, in Solwezi in the North Western Province. She traded arranging furniture to begin her new job in a hard hat and overalls. Now back in Lusaka, she wears a suit and is making a mark in the male-dominated industry.

“After a while, you get used to it. I think my background, especially in the JSE, is that I don’t feel the pressure. I had good mentors. If you are not going to do something don’t string me along. Don’t sit quietly and give me excuses later on. It’s just a waste of time and money.”

Kansanshi’s is a story of good news and the bad. Thanks to copper, Solwezi has become one of Africa’s fastest growing towns in a few short years. It was once a tiny village on the northern borders of Zambia 16 kilometers from the border of the Democratic Republic of Congo, 581 kilometers from Lusaka, and a million miles from the rest of the world.

According to research by the International Council on Mining and Metals (ICMM), mining is on the rise in 2012, 32% of tax revenue collected was from mining; in 2008, the percentage was half that. The bad news is that the mines have to deal with lack of infrastructure and skills development, says Dlamini.

“It needs a combined effort, not just the mines. The local authority needs to play a significant role in terms of town planning, in terms of creating social services. If you look at the mines there, Solwezi is one of the richest authorities in terms of revenue from mining authorities. But the challenge is we don’t know if that money is remaining in Solwezi or is dispersed to other towns in the country. The infrastructure in Solwezi is non-existent. Everything is clustered around one street, because there is a lot of emigration, there are a lot of social evils coming into the town,”

says Dlamini.

According to Dlamini, the reliability of data collection from both government and private sectors is also hampering investors. The Zambian government records mining GDP contribution to be at 8% when it should be 12% when researched by the ICMM, she says.

“Our biggest challenge is changing the perception of the mines. We need to get the facts straight. This is the backbone of the economy. At the end of the day, it’s finding that balance where we don’t irritate investors and irritate the government,” she says.

Despite its challenges, Zambia has won back its claim to be the copper power house of Africa. At the helm is Dlamini. She might be new to the industry but she knows all about making money, taking risks and losing it all. There is no doubt that the mining companies and government will find her one tough nut to crack.

Loading...