On July 7, 1985, South Africa’s Kevin Curren walked out onto the hallowed green grass of the Centre Court at Wimbledon as the favorite to win the biggest title in tennis. A kid, from Leimen, in West Germany, smashed that dream.

The fresh-faced, 17-year-old, Boris Becker, surprised the world by winning that match and becoming the youngest champion at Wimbledon – a record that still stands. Curren wasn’t surprised though, just disappointed.

“I was playing an unseeded guy. He had won Queen’s (the London tournament that serves as a warm-up for Wimbledon) two weeks prior, and in the final there he beat my good friend Johan Kriek who said ‘if he plays like this he can win Wimbledon,’” says Curren.

It had all been going so well. The year before, Curren reached the final of the Australian Open but was beaten by Sweden’s Mats Wilander. He also won a doubles title at the US Open in 1982 and mixed doubles titles at the US Open in 1981 and 1982 and at Wimbledon in 1982.

Kevin Curren

Loading...

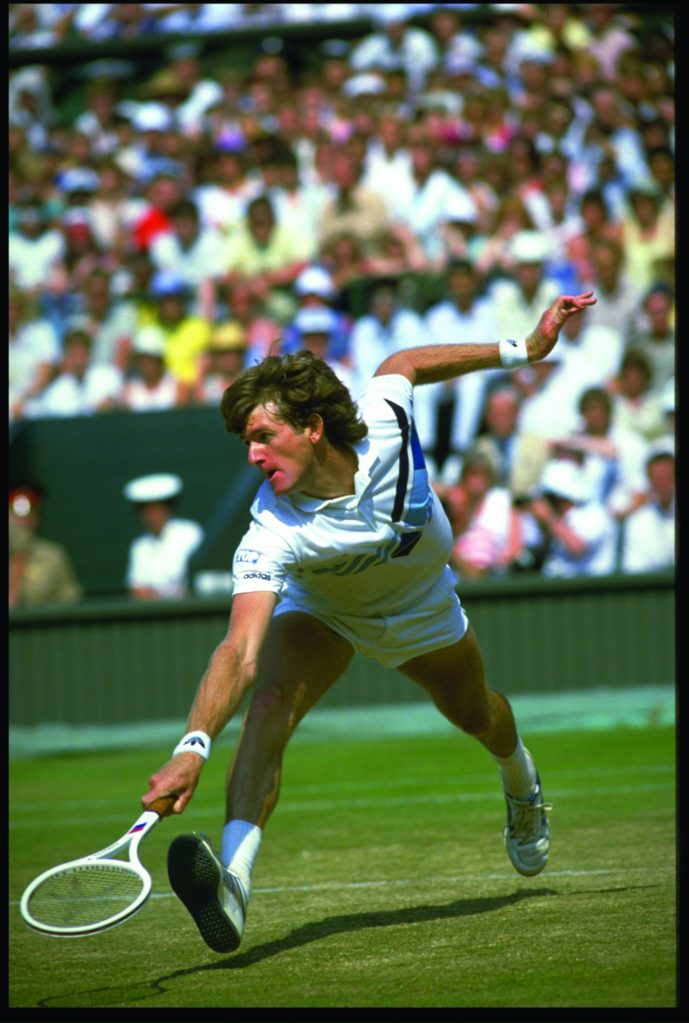

At Wimbledon, the South African was on top form and had beaten top-ranked players, John McEnroe and Jimmy Connors, on his way to the final. Beating Becker was meant to

be easier.

“McEnroe said to me he couldn’t believe I lost to a 17-year-old. I had beaten McEnroe and Connors convincingly. But, I think we underestimated how good Boris was because he came back the next year and won it again. He is the youngest winner of all time and I don’t think that record will be beaten. He was like the Tiger Woods of tennis to win it at such a young age,” he says.

“I said to McEnroe ‘he’s a lot better than you think.’ But McEnroe still insisted that I should never have lost that match. A month later, they played on the United States hardcourts – McEnroe was the world number one at the time – and he snuck through. McEnroe came to me afterwards and said ‘I see what you mean, he’s a lot better than I thought.’”

Curren says Becker’s age worked against him.

“[Becker] played as though he’d have a thousand chances to win Wimbledon. He was young and naïve and played as if we were having a game in his backyard. He didn’t comprehend the pressures of winning that title. That probably worked against me a little.”

Despite not winning, the final against Becker was the highlight of Curren’s career.

“It is the pinnacle of the sport. Wimbledon is a title, venue and tournament held in the highest esteem by all the great players. I did get to the final of the Australian Open but Wimbledon is special,” he says.

“When I look back, I take the view that I came from Durban and played with two hands. I had to convert my entire game. I think I beat the odds and most guys wouldn’t be able to do that today. I was fortunate and had some lucky breaks. I did very well with what I had.”

It could have been Lord’s rather than Wimbledon.

“I actually excelled at cricket. I had the top batting average at under-15 for KwaZulu-Natal and things were going along nicely. I was picked for the first team to tour but had to go with my family on a holiday. The next year, when I came back as a 16-year-old, I was told by the coach that I wasn’t going to be picked for the first team that because I didn’t go on the tour. I served my six-game suspension and when I finally got a chance to get back in I was demoted in the batting order and it broke my spirit.”

It was a blessing. The lack of cricket forced Curren to focus on his tennis. The sport earned him a scholarship at the University of Texas and eventually allowed him to gain citizenship in the United States (US). During apartheid, South African sports teams were barred from playing internationally. Becoming a US citizen allowed him to “play as an independent contractor and play around the world,” he says.

Today, Curren runs the Telkom Supersport Shootout – a golf tournament geared for top businessmen, government officials and sport legends.

“We own the Champagne Sports Resort in the Drakensburg. It started as a marketing sports event and mushroomed into a standalone business.”

Along with spending time with his wife and two young children, Curren plays a lot of golf on the South African Senior Tour.

“My challenge is to see if I can get my South African colours. I’m often playing against former pros who have taken their amateur status back. In tennis, I’ve climbed my Everest, I’m on the slippery slope down. But in golf, I’ve still got my Everest to climb.”

Don’t be surprised if he reaches the summit.

Loading...