He sweated on English pitches, he sweated on African pitches; he broke records and won a World Cup, but on the proudest day of his life he stood in the middle of St Mary’s Stadium, the home ground of English Premier League side Southampton. It was the moment he was made honorary president of the club that he made 815 league appearances for.

Five minutes later, Terry Paine watched from the comfort of his comfy corporate seat as Southampton goalkeeper, Arthur Boric, dropped the ball in the penalty area causing a mad scramble. A few seconds later, a fan sent an SMS: ‘Mr President, change the f—ing goalkeeper’.

“Oh my God, what have I gotten myself into now?” thought Paine.

It’s all part of the rich tapestry that is being president of Southampton. This season, Paine will make a 13,000km journey, leaving his home in Rivonia, Johannesburg, at the crack of dawn on his way to a football match. He lands at Heathrow airport, then a chauffeur drives him to his seat in the stands. On match days, it’s his job to win the hearts of businesspeople in the corporate boxes.

“The nice thing is I can say, listen I want to go to the Liverpool game, and they automatically get me into the boardroom there. This is an inner sanctum where there is no media or public. You’d be surprised at what you learn there. It’s the heart of business now, sport goes out the window… and it’s all about survival,” he says.

Loading...

It’s a fitting final chapter to a story that began 57 years ago, just an hour’s drive from Southampton. The club spotted him dazzling on the wing for Winchester City and signed him. In 1956, at the age of 17, Paine made his debut in professional football. A distinguished career led him to the 1966 World Cup, where Paine played against Mexico. The ball hit him in the face in an era when there were no substitutes. He was pulled off, slapped around and then told to get on with it. All Paine remembers is waking up on the physio table, in the changing room, after playing the whole game with concussion. England won 2-0 and Paine can’t remember a minute of it.

It is almost an understatement to say it was a different world back then. The tournament directors decided to give the 11 English winners £22,000 in prize money. The players divided the money equally within the 22-man-squad. It proved a 43-year wait for Paine’s medal. In those days only those who played in the final got a medal. In 2009, then British Prime Minister, Gordon Brown, handed over the medal.

“Nowadays you would expect a World Cup side, with all the spin-offs and sponsors, to collect £3-4 million,” says Paine.

In his latter years, Paine played for Hereford United and Cheltenham Town notching up 937 matches as a professional.

Paine fought for an end to the minimum wage in football, even though it came a bit too late for him. Paine watches over players, who will earn more in one afternoon than he would have seen in a lifetime in a world away from agents, mobile phones and modeling contracts.

When Paine started playing professionally he was paid £17 pounds a week. It was a pretty penny he says, compared to his father, who earned £3.50.

“My match bonuses were incredible; £1 for a draw and two for a win,” he says.

It was in the 1960s that Paine along with former Fulham player and head of the Professional Football Association, Jimmy Hill, urged players to strike for money. The problem was whether you played for Manchester United or Hartlepool United you could earn a pittance and no more.

“I remember Tommy Trinder, a famous comedian and chairman of Fulham Football Club, saying ‘I am going to pay our English captain Johnny Haynes £100 a week if it was lifted’. Well the day it was lifted Haynes came to collect. We were the pathfinders to where they are today,” says Paine.

Paine believes footballers deserve every penny they get. The problem he has is when clubs spend 90% of their money on players when they should be thinking about club finances.

“I think the guys in the Bundesliga have got it right. They open their books at the beginning of the season and declare how much they can spend. If a club does well like Bayern, they can spend €25 million, if they do badly they can only spend €15,000,” he says.

Paine also sees the wealthy generation of footballers as having lost that dash of old-school flair.

“Take South America for example and Brazil they are never going to be the side they were with Pele, pure and simple, because all the players when they used to play in South America, had the flavor of the Samba. Now they go and play in Europe, a little bit of that goes out. In some ways the game hasn’t quite got flair. It’s a good thing we got the Messi’s and the Ronaldo’s of today. But I don’t think there is the individual flair coming out of the players, in our day there seemed to be so many,” he says.

Paine’s career was forged in England and seasoned in Africa. His first taste of Africa was with the Bobby Charlton XI team, in 1979, where he played alongside England’s retired internationals including England World Cup winning captain, Bobby Moore. Paine says he will never forget walking onto the pitch at the Orlando Stadium in Soweto and seeing 80,000 screaming fans, with another 80,000 trying to jump the fence from outside. In those days he was blown away by the passion of the fans on the streets. On a minor note, he will never forget the R9 breakfast buffet in the Alengani Hotel in Durban, paid for by his £1-a-day budget.

Paine was captivated by Africa. He left Hereford United to coach South African amateur players with Robertsham Football Club in Johannesburg. He also had stints with Bedfordview Country Club, Witbank Black Aces and Wits University.

“Some of these guys were the best players I have ever seen, even better than in European leagues, all they needed was a bit of organization and they were unbeatable,” says Paine.

This is where football in Africa falls short he says. He was disappointed by African football at the FIFA 2010 World Cup.

“They have so much talent within their ranks they just can’t seem to get it together. It comes to organization and planning for the future. Ghana, Zambia and sides like them do produce players. It has been disappointing that they haven’t kicked on to win a World Cup,” he says.

Football has taken on a more professional approach since Paine’s day. In the very same place where he grew up playing Sunday 22-a-side matches, at King George V’s fields, is the Southampton Junior Academy.

In Paine’s day you were lucky if you got an orange at half time. These days, the young stars of England have their mouths swabbed by experts to see whether they are sick. Their shirts are washed in non-allergic soap. From the age of eight, players run out on a manicured pitch fit for Wembley.

Paine is adamant over certain aspects of the game. He thinks Manchester United’s George Best was better, by far, than Eric Cantona. When it comes to Africa, the best are: George Weah; Abedi Pele; Kalusha Bwalya; Roger Milla; Gary Bailey and Yaya Toure.

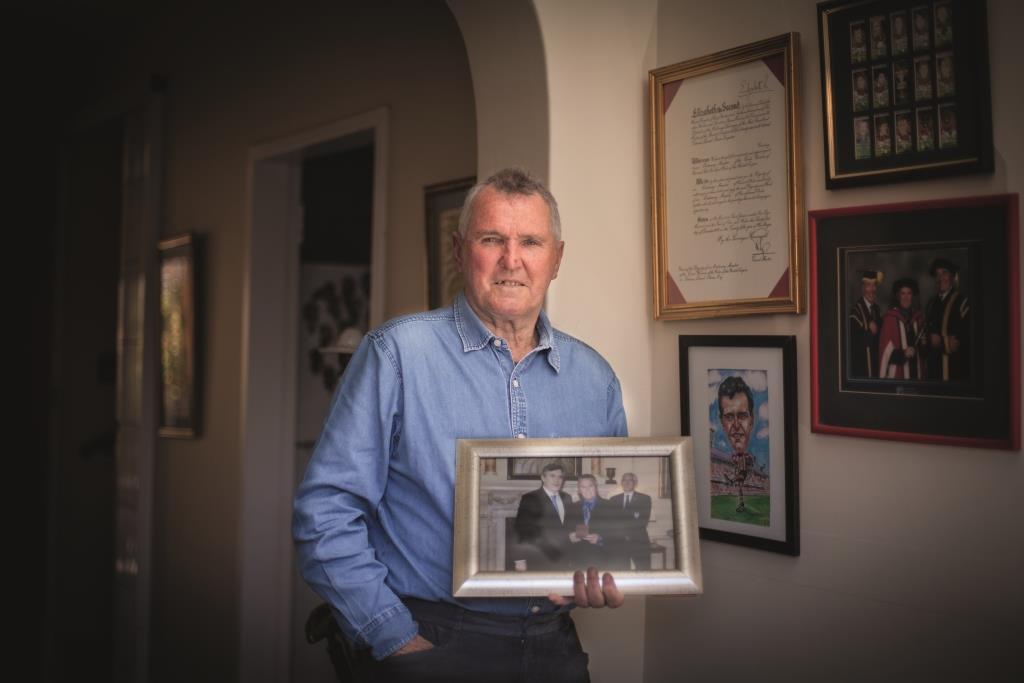

When he is at home, he likes hacking at golf balls and flicking through his memories in photographs and books. Most of his memorabilia has been given away or sold, he says. This includes his World Cup medal, which went on auction in 2011, where it sold for £25,000.

Since he became president of Southampton, the fan mail has flowed in to Rivonia. Many ask for an autograph, which Paine is happy to sign, but gripes a little about the R460 ($46) cost of sending them back. If you are a president and a legend it’s just another day—but what about that goalkeeper?

Loading...