One name was in the head of Cameron van der Burgh amid the lights, screaming and chaos at the poolside—that of his friend, Norwegian world champion swimmer, Alexander Dale Oen. Just a few months before, Dale Oen was altitude training in Arizona, in the States, looking forward to winning gold medals in London. On April 30, the 26-year-old collapsed and died from a rare heart complaint.

“We were friends and I was training to beat him when he died and it almost felt like he left something with me that helped me with my journey. As you can see, at the end of the race there is a picture [of me] pointing to the sky in his honor. It was relief that I was able to achieve what I wanted to do with the help of someone to look after me. I felt I was swimming with him,” says van der Burgh during a visit to FORBES AFRICA in Sandton.

“I would always go fast, so in the second 50 meters, I would fatigue. Alex was always very fast in the second 50 and so was I in this race. I could almost feel maybe this guy was smiling down on me afterwards… When I got home that night I looked at the medal and reflected. It is like you have to study for four years for one final exam, lasting 58 seconds, if you fail you go back to day one. I was very lucky to be on the other end of the scale.”

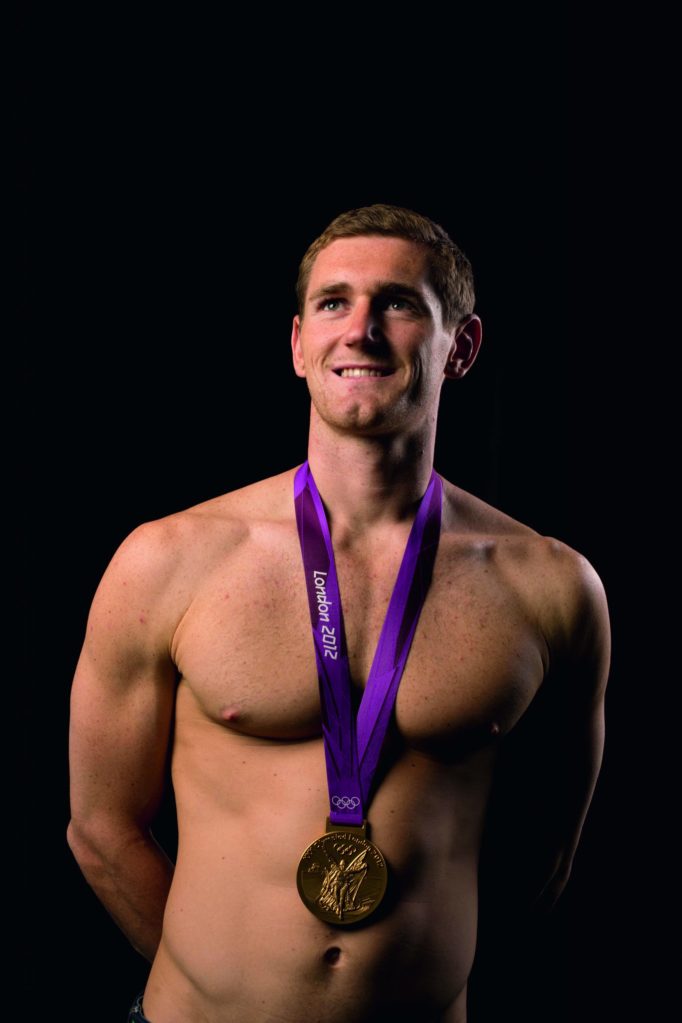

Swimming: 2012 Summer Olympics: South Africa Cameron van der Burgh victorious after winning gold with world record time of 58.46 seconds during Men’s 100M Breaststroke Final at Aquatics Centre.

London, United Kingdom 7/29/2012

CREDIT: Peter Read Miller (Photo by Peter Read Miller /Sports Illustrated/Getty Images)

(Set Number: X155279 TK5 R1 F131 )

Van der Burgh, born-and-bred in Pretoria, South Africa, is the grandson of a Karoo farmer and probably one of the most polite and unassuming world champions you will ever meet. You wouldn’t bat an eyelid if you saw him cleaning his dad’s pool in the Pretoria suburbs. He is also a man who believes in home; he turned down offers from Australia to become the first-ever world swimming champion to be trained in Africa. Along with his fellow South African gold medalist, Durban-based swimmer, Chad le Clos, he believes their win could boost swimming in South Africa.

Loading...

“We have shown the country that swimming is worth investing in. There is a lot of money out there and I am sure the guys in rugby and cricket will be complaining because we will be taking money away from their sports,” he says.

On the face of it, van der Burgh is the consummate narrow-eyed sport professional. Since the age of 11, days when he beat all-comers easily, without training, his cellphone PIN has been 2-0-1-2, his year for the Olympics. By the age of 16, he was losing heart and could have tossed it all away if it hadn’t been for a painful freak accident.

It was the South African national championships in Durban and van der Burgh hadn’t made the finals and was beginning to wonder if he ever would. Instead of tearing through the pool he was out of it and messing around with a mate on the high diving board.

“I jumped once and it was OK, the second time I was wet. There were big banners saying don’t jump off the diving board. I got to the top of the stairs, my foot slipped; I fell three meters onto the tiles and broke my ankle. Boys will be boys,” he says.

“Three months and two operations later I was recovering when I saw all my mates were training away and I wasn’t even able to jump into the water. It was then I decided to push myself further.”

It wasn’t easy. For four years, training began at 8am, with grueling hours in the pool and gym, followed by a massage until 6pm.

“It is a hard life. It is a lonely sport with lots of sacrifices. I do get lonely,” he says.

The fruit of this labor has been crazy days, far from lonely, with people drawn to him like flowers to the sun. On the eve of the semi-final he had to switch off Twitter because 10,000 messages a night were keeping him awake. People have asked him to sign their arms and legs; one man asked him to attend his child’s birthday party. You can be sure more than a few South Africans will name their children Cameron. He was also amused by entering the gold medal club.

“Gold medalists like Phelps are in their own world and they don’t talk to you. I noticed, the day after I won, that they nod to me now,” he says.

The man himself can’t wait to go surfing in Jeffreys Bay, off the east coast of South Africa. He learned how to surf three years ago and says he is very good at paddling.

The future lies in financial management, which van der Burgh is studying through the University of South Africa (UNISA). He has already invested in a company offering accounting services to the mining industry.

In January, he will begin training for the 2016 Olympics, which he is sure will be his last.

“I want to go back and win the medal. So then I have done my job and can haul my togs up. I see it like a gladiator—after you have finished your job you can live and you can be proud,” he says.

Africa will be proud too.

Loading...