When everyone else is running away from danger, war reporters hurl their cameras and microphones in the opposite direction to ‘get the story’. Paula Slier, the writer of this piece, is one of them.

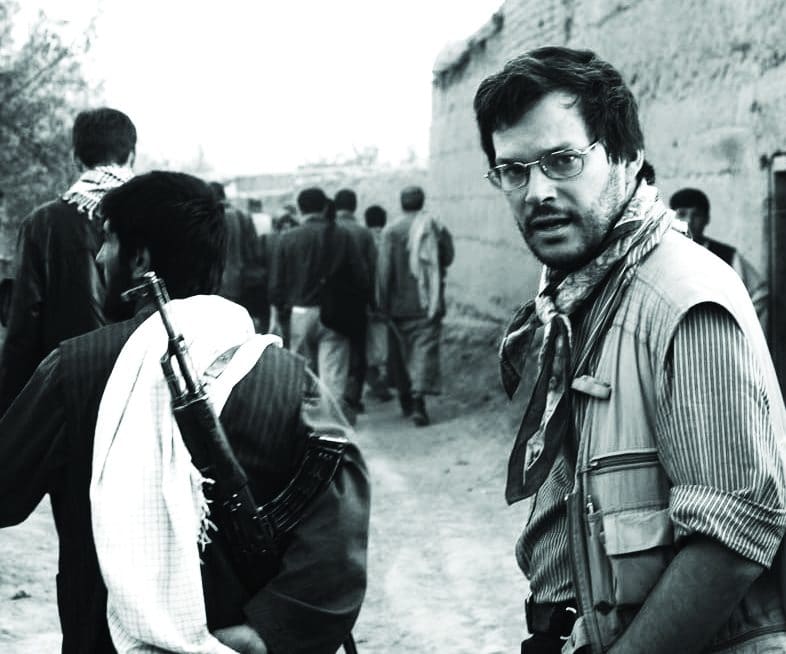

War reporting is more a calling than a profession. Why else would an otherwise sane adult throw himself or herself in harm’s way? When everyone else is running away from danger, these men and women are hurling their cameras and microphones in the opposite direction to ‘get the story’.

This year alone, 19 journalists have been killed in the field. It begs the question if the job is worth the risk? Especially in the age of Twitter, virtual reality and 360 cameras, can – and will – technology replace human coverage on the battlefield?

Wars today make no distinction between combatants and journalists. Long gone are the days that the reporter was perceived as a ‘neutral observer’. Today, increasingly, the media is seen as a legitimate-target in the so-called ‘information war’ that can be as important – if not more – in the fight for public perception, than the battle itself.

During the bloodiest days of the not-so-long-ago Russia-Ukraine conflict, I reported from the frontlines alongside pro-Russia fighters.

Loading...

I wore a bullet-proof jacket with the word ‘PRESS’ emblazoned across it. Instead of offering me some degree of protection as one would expect, the soldiers asked me to remove the jacket as they believed the Ukrainian military would deliberately target me because I was a journalist. I was thus making it unsafe for them too.

Award-winning Italian war reporter, Fausto Biloslavo, has covered most of the conflicts of the last 35 years. He believes this shift in how journalists are viewed came about after ‘September 11’.

“Insurgents no longer considered us witnesses to be respected but cannon fodder for propaganda or ransom. Nowadays, in any war, they always think that you are a spy and not a real journalist,” he says.

It doesn’t help that wars themselves have become more difficult to cover. The rise of non-state actors like paramilitary and terror groups means that, for years, swathes of Syria and Iraq were off-limits to reporters.

The only way a journalist could reach there was by being ‘embedded’ – attached – to an army unit. No wonder then that we are seen by some groups as unobjective and pushing a particular view. It is very hard to travel with the Kurdish army, like I did in northern Iraq, and be perceived by those fighting the Kurds as neutral.

Amitabh Revi, associate editor of Strategic News International, a niche Indian online news service, has had his fair share of warzones. He believes that some wars are simply too dangerous to cover.

“It’s always a calculated risk. When I ask myself why I do it, it’s to be the eyes and ears for those who can’t be there and frankly, just to be there myself. Social media and citizen reporting are important, but for sustained, comprehensive coverage, one still needs a professional.”

Small-sized digital equipment has seen the rise of the so-called ‘accidental journalist’. These often young, unqualified reporters venture into danger zones and take risks that their more seasoned colleagues never would. The trend became so prevalent that major news organizations took the unprecedented step of announcing they would not buy footage from freelancers reporting in areas they deemed too dangerous to send their own staff reporters to.

Biloslavo has lost five close friends to conflict.

The first was Almerigo Grilz, a kind of older brother to him. He was killed on May 19, 1987, in Mozambique. filming a battle between Renamo rebels and Frelimo government troops. Grilz made the mistake to move slightly from behind the protection of a termite mound to film the rebel retreat and was likely shot in the neck by a sniper.

“Almost always a journalist dies because he has made a mistake, small or big, conscious or not, as he travels along a dangerous road, photographing a tank around a corner or trusting the local population too much,” believes Biloslavo. And all the training in the world cannot prepare one for that moment. Often it’s instinct that kicks in at the last moment, especially when one must make that critical decision to move forward, stay put, or pull back.

“No article is worth the price of life, but someone has to go and report about wars, the dark side of humanity.

“It’s to be the eyes and ears for those who can’t be there and frankly, just to be there myself.

But despite all the risks, Biloslavo has no intention of laying down his microphone for good.

“I’ll only stop taking risks when I can no longer bear the weight of the bullet-proof jacket, the helmet, the backpack and am unable to run halfway through the whistle of the bullets,” he says.

“No article is worth the price of life, but someone has to go and report about wars, the dark side of humanity. This means accepting the risks of being killed, injured or kidnapped.”

For Revi, he’ll only stop reporting when wars stop, which implies never.

“The most dangerous situation I was in was during a so-called ‘double tap’ attack in Afghanistan,” he reflects. “The idea (of the perpetrators) is to kill the first responders – medical, security forces and journalists who rush to an attack. Instinct kept me away from the second of the two blasts. So, in short, one needs loads of luck.”

But what happens when that luck runs out? Sometimes, war reporting can feel like a ticking bomb. I narrowly missed a suicide bombing at the entrance to my hotel in Afghanistan. For three weeks, I had met the crew at the same spot every day at 9AM. On the day of the explosion, we had an early interview and left some 15 minutes before the bomb detonated – at the entrance, exactly at 9AM.

A mixture of faith and fate keeps me going. Faith in the importance of what I’m doing – writing the first draft of history – and fate that when my time comes, it’ll come, but not a second before.

As the US author, Horace Greeley, wrote: “Journalism may kill you, but it will keep you alive while you’re at it.”

– Paula Slier

Loading...