The São José-Paquete de Africa had been at sea for over three weeks when, just off Cape Town’s treacherous coastline, it was overcome by a bellowing storm. As gusty winds yanked at its sails, storey-high waves pushed the vessel closer to shore.

Captain Manuel João from Portugal refused to give in, after all was just a few sea miles away from Table Bay. The plan was to anchor there, stock up on food, water and other supplies, and sail on to Brazil to offload his precious cargo: 500 men, women and children from southeast Africa, packed like sardines in the dank belly of his ship. After delivering his load, João would return to Mozambique for a fresh shipment.

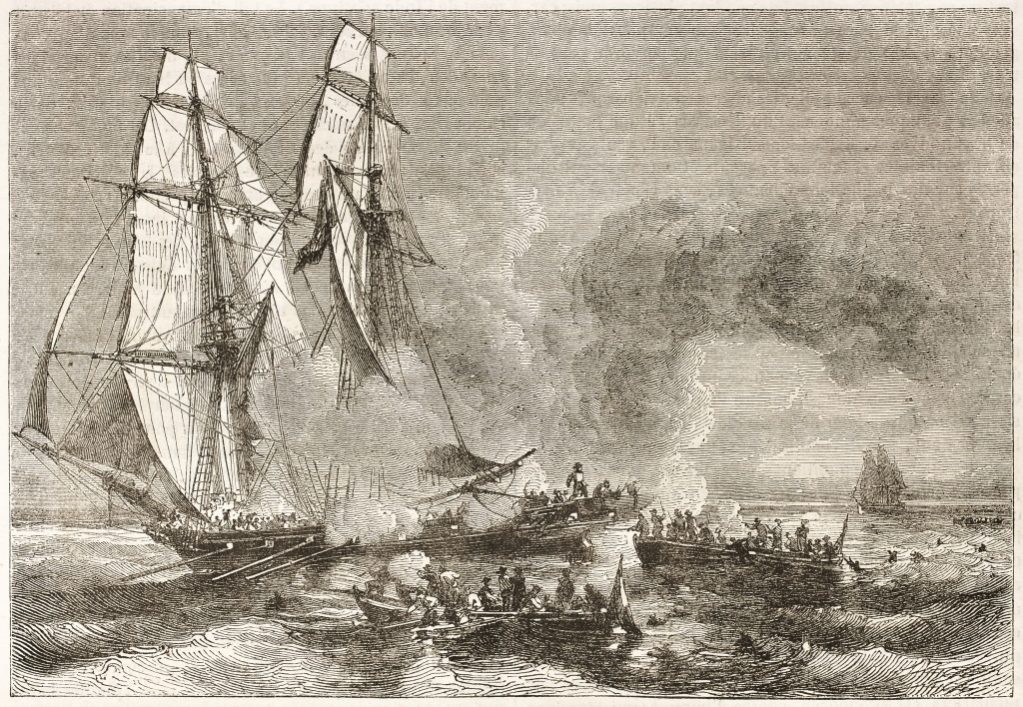

Mother Nature decided otherwise. On December 27, 1794, the São José smashed against razor-sharp rocks, 100 meters off present-day Clifton, an affluent suburb of Cape Town. The vessel disintegrated into matchwood and sank to the bottom of the Atlantic – taking 212 slaves with it. Those who survived were captured and sold into bondage in the Cape, possibly to recoup the damages.

The São José was soon to be forgotten, until sports divers stumbled upon her remains in the 1980s – after which the ship ended up in the archives as the Van Schuylenberg. This Dutch merchant vessel had gone down off the Cape coast in the 1750s.

Loading...

In 2011, South African marine archaeologist, Jaco Boshoff, came across an account by João, in which he described how the ship had left Lisbon on April 27, 1794, to purchase slaves from Mozambique. On the 24th day of the voyage to Table Bay, for an interim supply stop before crossing the Atlantic, the ship was overcome by bad weather and sank.

More information has since emerged from the archives in Portugal and Mozambique, as well as the bottom of the Atlantic, which suggested that the wreck off Clifton was everything except a Dutch merchant vessel. So, in 2014, the partners of the Slave Wrecks Projects – which includes Iziko Museums of South Africa, the South African Heritage Resources Agency, and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington DC – began unearthing what was left of the wreckage.

“We found iron ballast blocks, which were often used to stabilize slave ships. Human cargo tends to move around and is therefore more unstable than dead weight, hence the blocks,” says Paul Tichmann, curator of the Iziko Slave Lodge, a museum in Cape Town.

He adds that Portuguese archival documents confirmed that the São José had loaded iron ballast before departing for Mozambique.

“We also found slave shackles, copper nails, and sheathing,” he says. “Tests have indicated that these date back to the 1790s. The timber remains we have found, was proven to be a type of Mozambican hardwood, also dating back to that particular time.”

Unearthing whatever was left of the São José was not easy.

“It is a very difficult area for diving. The waters are very turbulent, with strong currents. One of the divers described it as working in a washing machine. There were times, they could only dive three days per month,” says Tichmann.

The discovery of the ship – which was announced in June – has been hailed as an extraordinary find, making headlines around the world. It is one the few transatlantic slave ship wrecks ever recovered.

The São José’s significance goes beyond that, says Patrick Harries, who has been studying the role of the Cape of Good Hope in the transatlantic slave trade for decades. The wreck, he says, has once again proven that the Cape – generally known as a refreshment stop for ordinary merchant ships – was an important service spot for slave vessels en route to the Americas.

“It served as such from the mid-1700s to 1834, when the trading and owning of slaves was abolished in all British territories,” he says, adding that slave ships anchoring in Table Bay were transporting slaves who had embarked in Mozambique, southern Tanzania, and Madagascar.

“Many were brought to the coast after being captured in the deep interior, for instance where Zambia and Malawi are now,” Harries says.

“They were then loaded onto ships in Mozambique, which would then sail to Table Bay to refuel prior to sailing on to their final destination. Close to half a million slaves were taken from southeast Africa.”

While supplying slave ships with wood, food and water, thus making a profit out of the transatlantic trade, Cape Town also absorbed some of these slaves.

“Generally speaking, a ship owner would sell 10 percent of his slaves in Table Bay to pay for the fuel and supplies,” Harries says. “They would end up working on farms.”

While the Dutch shipped East Africans into the Cape, they didn’t play much of a role in the transatlantic slave trade. The trade in humans from southeast Africa to the New World started under the French in the 1770s.

“The French had been using African slave labour since the early 1700s to keep the sugar plantations on Reunion Island and Mauritius going. They started transporting East Africans across the Atlantic upon realizing that they were worth more in Saint-Domingue than in Reunion,” says Harries.

Situated in the Caribbean, Saint-Domingue used to be the sugar capital of the world.

“Sugar was the petrol of those days, making it the jewel of the French empire,” says Harries.

The tide turned in 1791, when slaves in Saint-Domingue staged an uprising and took control, renaming the region Haiti. This put an end to the French East African slave trade.

Like their French counterparts, Portuguese and Brazilian slave ships stopped in Table Bay for supplies before crossing the Atlantic.

“Particularly the months between October and March, known as the slave season, were busy. There could be as many as three ships in Table Bay, each carrying 300 to 400 slaves,” says Harries.

Cape Town continued to service slave ships until December 1, 1834, the year the trading and owning of slaves was outlawed. This prohibited any slave ship from anchoring in Table Bay and put an end to the Cape’s transatlantic slavery role. This didn’t end the influx of cheap African labor into the Cape.

“In 1834, the Brits had granted themselves the right to hunt down any slave ship within their waters. The slaves on board these captured vessels were brought to British controlled territories, the Cape included. Here, these so-called ‘Prize Negroes’ were sold on as apprentices, for up to 14 years,” says Tichmann.

The ‘Prize Negroes’ were often worse off than slaves.

“Apprentices were a prized and expensive commodity. Those who bought apprentices felt they had to get the most out of them as long as they could legally have them. Conditions were therefore very harsh. They would not get paid. It was another form of slavery, really. This happened until the 1880s if I am not mistaken,” says Tichmann.

Records show that 3,000 to 4,000 ‘Prize Negroes’ were imported into the Cape, on top of the previously mentioned 63,000 African, Asian and Indian slaves.

Both Tichmann and Harries hope that the São José discovery will trigger a greater level of awareness around Cape Town’s role in the slave trade.

“South Africa always thought it was safe from that particular history, but in fact, the transatlantic trade in Africans is very much part of it,” Harries says. “It is important that people in the Western Cape acknowledge this. A large part of its population, after all, are descendents from these African slaves. Their ancestors survived a month in a slave ship, and experienced the most awful conditions imaginable. We need to remember,” says Harries.

Loading...