While Kenya marks and celebrates 50 years of independence in December, many are not convinced that the country has achieved its full potential and believe it is far from meeting citizen expectations. Many years after Kenya achieved its independence from Britain, poverty, illiteracy and disease continue to thrive in the country.

Even though there has been some progress, much more could have been accomplished. Kenya is still grappling with the same basic problems that were supposed to be defeated at the inception of the country but many feel nothing has been achieved to warrant any applause.

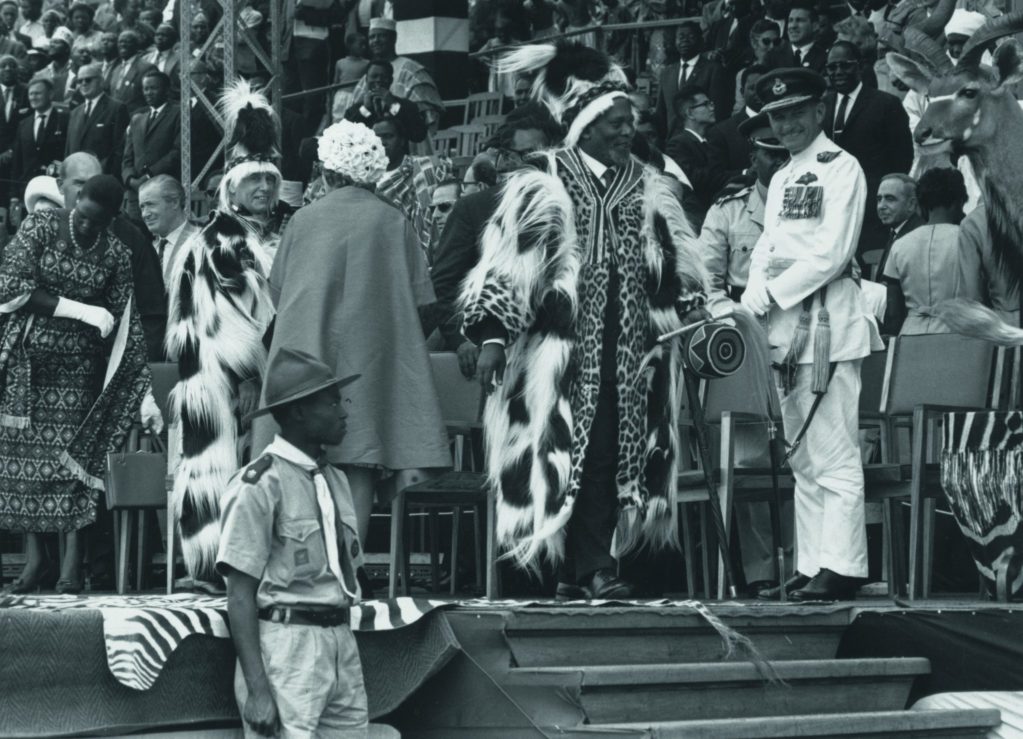

Mau Mau leader of Kenya African National Union (KANU), Jomo Kenyatta, holds the official document of Kenya independence, December 13, 1963 in Nairobi as he became President of Kenya. At left is Prince Philip of Edinburgh representing Queen Elisabeth for the ceremonies.

Skyrocketing food prices and the high cost of living are the main challenges facing the nation, and must be addressed to significantly improve the people’s living conditions.

The gap between the poor and the rich has widened while poverty has made many dependant on others. This is not the independence that Kenya and Kenyans need. This must be addressed through government creating more job opportunities for the high number of unemployed.

Loading...

There is fear that resources are not allocated equally and in the next 50 years the government must address this. Kenyans expect nothing less than equality in allocation of national resources and the creation of jobs across the country, so that people in all areas have opportunities to better their lives.

The new constitution and reforms associated with it have begun to usher the country into an era of accountability, transparency and good governance. But to safeguard the gains made so far and to secure the progressive future that constitutional reforms promise, the nation must effectively address the rising insecurity in Kenya.

Kenya’s new constitution is a progressive document that aims to address the failed legal and moral systems created by earlier colonial and postcolonial regimes. The country’s previous constitutional order alienated most citizens from the state, but minority and indigenous communities have borne the brunt of this exclusion. This system reproduced and strengthened differences between Kenya’s diverse groups—mainly ethnic and religious—rather than building a pluralistic society that tolerates all shades of diversity based on equality before the law.

The history of Kenya is one in which its rulers have consistently demonstrated an insatiable appetite for human sacrifice. Some of the country’s most brilliant leaders have been assassinated, from Tom Mboya in 1969 to JM Kariuki in 1975 and Robert Ouku in 1990.

Founding president Jomo Kenyatta—father of the present leader—ruled the country from 1963 to 1978 like a monarchical patriarch, enriching himself through large tracts of state land. Despite having been jailed by British colonial authorities for being a leader of the Mau Mau armed struggle, Kenyatta relied on Pax Britannica—through a British defence pact—to protect his regime. These pro-western policies were challenged by his vice-president, Oginga Odinga, who lamented in a 1967 autobiography, Not Yet Uhuru, that the country had not yet attained full independence.

The heroic Mau Mau struggle from 1952 was one of the greatest anti-imperial movements and exposed the brutalities of the British authorities who tortured and killed at least 20,000 liberation fighters and imprisoned another 150,000 people in concentration camps. Kenyatta’s death in 1978 saw the rise to power of Daniel arap Moi.

In a country with deep ethnic divisions, it was important that a Kalenjin replaced a Kikuyu. Moi ruled for 24 years with an iron fist and was a crude autocrat who introduced one-party rule and queue-voting that violated the sanctity of the secret ballot. His regime became increasingly draconian after a failed coup in 1982, with violence being used to whip up interethnic tensions in bloody elections in 1992 and 1997.

Corruption scandals proliferated, and combined with Robert Ouku’s murder, eventually pushed previously tolerant western patrons to press their client to introduce multiparty democracy and observe presidential term limits.

A pro-democracy alliance finally triumphed in 2002 under the leadership of Kikuyu politician Mwai Kibaki, Moi’s former vice-president. Kibaki’s stealing of a presidential election in 2007—widely believed to have been won by Raila Odinga—triggered some of the worst interethnic clashes in 2008 in which 1,500 people were killed and 600,000 displaced. The president shamefully had himself sworn in like a thief under the cover of darkness. The 2008 violence centered on Kikuyus and Kalenjins in the Rift Valley. The political marriage of convenience sealed by the present Kikuyu president and his Kalenjin deputy and fellow International Criminal Court (ICC) indictee, William Ruto, helped calm tension during the recent elections.

Political power in Kenya has been used to acquire economic power, thereby placing an additional premium on the necessity of acquiring political power. This has been taken to absurd levels, where particular leaders have used their political positions to illegally acquire wealth and, upon being called to account, have said that their ethnic groups are being persecuted politically.

However, even when a particular community is in power, the perks are only enjoyed by that community’s elite. It does not always translate into a tangible benefit for the ordinary people.

Kenya’s next 50 years will hopefully benefit heavily from the foundations set in the last decade and firmed up in 2010 by a new constitution, which has given massive powers to institutions rather than individuals. As Kenya builds towards its centennial celebrations, the challenge is to foster a tolerant and more secure society.

The country is poised for an expanded economic portfolio thanks to the discovery of major oil and gas deposits in the Rift Valley and the Kenyan coastal regions respectively. The entry of Tullow, Anadarko, Cove Energy, First Australian Resources (FAR) Limited, Pancontinental and Total among others shows an economic boom long before 2030. With the passing of the Kenya Mineral and Mining Policy 2011, Kenya too is set to open up its mining industry covering gold, iron ore, titanium, coal and other precious stones. Improved infrastructure will enhance more intra-regional trade and boost a robust service industry.

Away from economic transformation is the new socio-political-economic model set in the counties system, which will be replacing the colonial provincial administration scheme. Under the new Kenya’s administrative stations, there are 47 new counties as opposed to the original eight provinces in the past. Fifteen percent of the national budget will go to the county governments.

Loading...