On a winter’s afternoon in July two men—born in the same country and infused with the same revolutionary fervor—will shake hands at the spot that changed their lives, to bury a 50-year-old grudge.

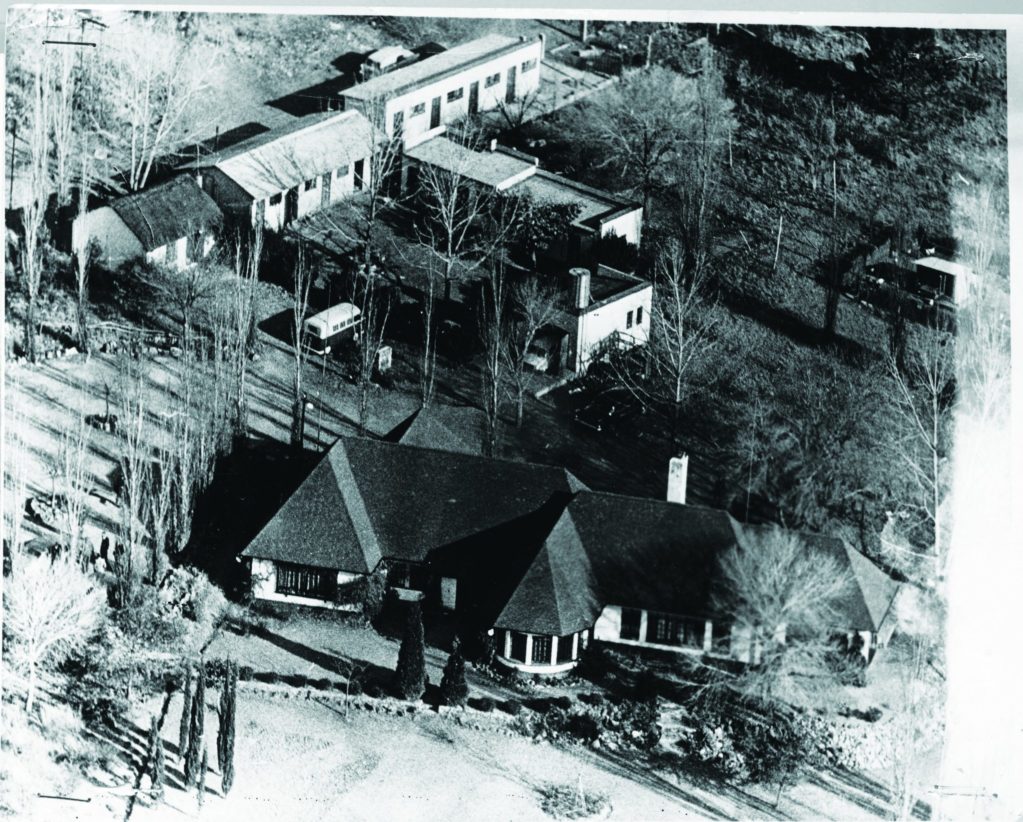

The men were among those arrested in the raid on Rivonia on July 11, 1963. Armed police with dogs used a delivery van, as a Trojan horse, to sneak into Liliesleaf Farm, in Rivonia; they arrested the entire leadership of the underground movement. The raid dealt a body blow to the South African liberation movement, not long after it had launched an armed struggle. In the resultant Rivonia Trial, Nelson Mandela, who had been in prison since his arrest in August 1962, was sentenced to life, along with his comrades.

The arrest at Liliesleaf was to send the lives of comrades Bob Hepple and Denis Goldberg spinning in opposite directions.

Eighty-year-old Denis Goldberg—the bomb maker—who had returned from a trip to procure hand grenades, was arrested as he sat reading in the lounge. All were chained in a circle outside the thatched cottage, while the police encouraged their dogs to snap at them. He spent 22 years in prison after the judge handed him four life sentences.

Loading...

“They gave me a 75% discount and I served only one,” laughs Goldberg, who often salves pain with humor.

It was a hard time in prison for Goldberg, who nursed the leader of his defense counsel, Bram Fischer, through his final days as he died of cancer. After the Rivonia Trial, Fischer had been charged with conspiracy to overthrow the state and sentenced to nine years.

In the other direction: Hepple suffered under interrogation; agreed to turn state witness; had charges withdrawn; skipped South Africa, via Botswana and Tanzania, for London; enrolled at Cambridge University, where he became a professor and a knight of the British realm.

Back in 1963, Hepple, the son of a former Johannesburg member of Parliament who was a meat wholesaler, Alex Hepple, was an underground activist, who had the misfortune of being at Liliesleaf on the day of the raid. Police had also caught the entire leadership of the underground as they held a meeting in a thatched cottage at the back of Liliesleaf: Govan Mbeki; Ahmed Kathrada; Andrew Mlangeni and Walter Sisulu. Behind bars, all were interrogated. The severity of the situation dawned on Hepple.

“The prosecutor told me all of us could expect to be sentenced to death,” says Hepple.

“This was not the reason for my decision. I never intended to give evidence for the state, but saw the prosecution’s offer to release me as an opportunity to escape. I discussed this possibility beforehand with Mandela, who said I had to take a personal decision, but if I could get the prosecution to release me: ‘That would be excellent.’ Had they not released me, I would have refused to testify against the other defendants, when called to the witness box.”

In the cells, the other defendants were not so comfortable, especially Goldberg.

“At the time it was very distressing, because he might give information about us. His father told him that the minister of police, B.J. Vorster, had said they have enough evidence to hang Bob. And that if he wanted to get out he had to give evidence. I’m very relieved that he left the country and did not give evidence. At the time, it was hard to swallow. Now that I look back over the years, it’s a long time ago and I know, from my own experience, that people can be broken under pressure. And I had to draw the distinction between those who were broken and gave evidence and those who simply stopped and did not give evidence. Bob didn’t give evidence in court anyway.”

Nearly half a century on, Hepple, accused number 11, recalls the moment he walked free from the Palace of Justice in Pretoria.

“As I left the dock, Mlangeni said: ‘I am glad you are getting out of this,’” he says.

A sour taste lingered. Years later, Goldberg says that Hepple sent him a birthday card to the Pretoria prison. Goldberg remembers this with a smile.

“I told my wife that I never want to hear from him ever again,” he says.

Goldberg, who is now retired in Hout Bay, near Cape Town, was released in 1985 and escorted onto a plane to Israel, where his daughter was living. He spent the rest of his struggle days organizing for the ANC in London.

In the early days of freedom, Goldberg went to a party in London where Hepple was also a guest. The host said he didn’t want any trouble and Goldberg assured him there would be none.

“I saw Bob at the party, I held out my hand, but he walked straight past me,” says Goldberg.

Hepple remembers it differently.

“I admire and respect Denis and the other trialists and am always happy to meet them. Denis may have forgotten that we shook hands at a party in London, sometime after his release.”

Hepple thrived in the United Kingdom and enjoyed a distinguished legal career culminating in becoming a Professor of Law at Cambridge University between 1995 and 2001. He was knighted by Prince Charles, who was deputizing for the Queen, in 2004. The irony of a former wild-eyed terrorist being knighted by one of the heads of the British establishment, surely could not have escaped him as he knelt with the sword on his shoulder.

“I honestly can’t remember what was going through my mind. I may have been remembering Mandela’s parting words to me that I will not be judged by the past, but rather how I conduct myself in the future,” says Hepple.

Goldberg could have heeded the same words. He travels the world speaking and raising money for health and education and is at peace with the past.

“It is fifty years ago, I don’t have any anger about it anymore and too many people did too many worse things of betraying us, killing our own people and yet they were accepted back into society. So I have no bitterness against Bob at all. I believe he says we did shake hands, but I don’t remember,” he says.

When the two men shake hands on July 8, at Liliesleaf, near the spot where they were arrested, at a ceremony to commemorate 50 years since the raid; it will be a fitting place to close a circle born of struggle and strife.

Loading...