June 12, 1964 was a cold and miserable day for Denis Goldberg and his comrades. They shuffled out of the cells and up the wooden steps to the courtroom at the Palace of Justice, in Pretoria, expecting to be told they were going to die.

Goldberg had stood shoulder-to-shoulder with Nelson Mandela, Walter Sisulu, Govan Mbeki and other activists facing charges of sabotage. Mandela and his comrades spent months in the cells contemplating how large the death penalty loomed.

Former South African president and Nobel peace prize laureate Nelson Mandela (L) greets former political prisoner Dennis Goldberg (R) during a Lunch for Apartherid former political prisoners at Genadendal, the official residence of the president, in Cape Town, South Africa on February 12, 2010. AFP PHOTO/GCIS/HO/Elmond Jiyane –RESTRICTED TO EDITORIAL USE—

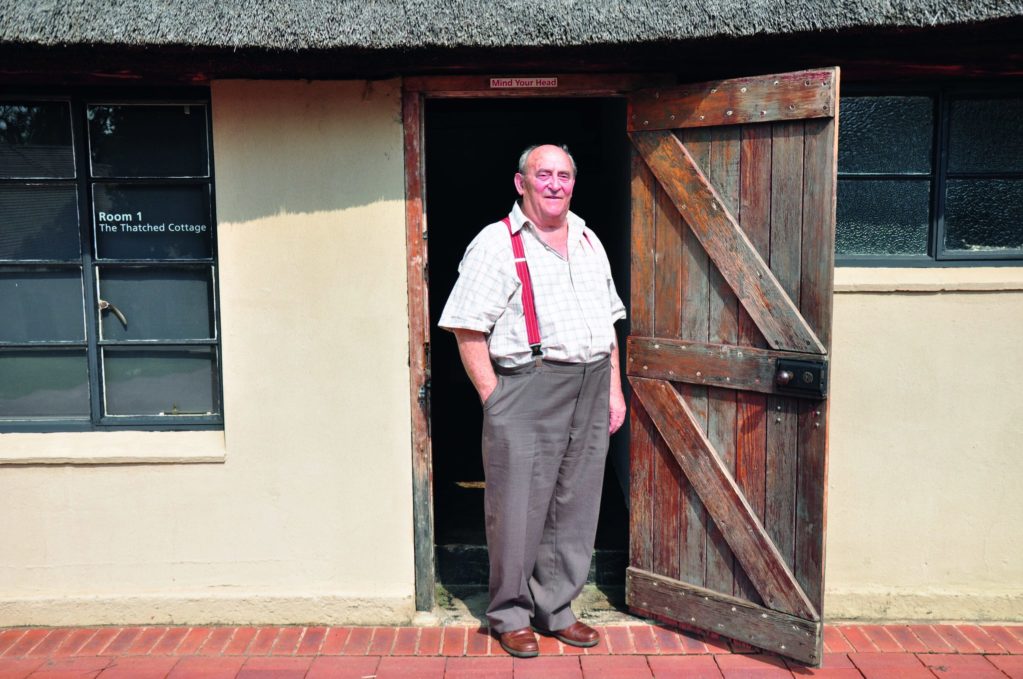

“One day he says to me ‘Denis, I want you to know that when you teach poor people about Marxism, don’t talk about slavery and feudalism and mercantile capitalism, that’s European stuff our people don’t know or understand it, it’s meaningless. You have to talk about Southern African society, how we get to be where we are, the working class and this and that.’ And I said to him, ‘I understand that but why are you telling me?’ He said ‘Oh, I just want you to know what I think’, we didn’t take it further but I was quite sure he was confident, no, certain, that he was going to be hanged,” says Goldberg at Liliesleaf, in Rivonia, near Johannesburg, where he was arrested nearly half a century ago ahead of the trial of the century.

Tension was high in the packed courtroom on that fateful June day, where the judge surprised many by handing down life imprisonment, instead of the death penalty.

Loading...

“And it dawned on us that we weren’t going to die, not then anyway, and we laughed, my memory is we laughed. Two great moments in that trial, the other one is Nelson daring the judge to hang him, hang Walter, hang Dennis, hang them all and then, that not happening. What a moment,” says Goldberg.

“About a year ago, I asked him why they didn’t hang us, he said: ‘I dared them to and they didn’t dare.’” He has always had this simple psychology; you stand up to people and dare them to the limit. I think it’s more complex, than he’s saying, but that challenge was a very important challenge. Here, were thoughtful leaders.”

Imprisonment, on that cold June day, was the end of a short but memorable association with Mandela. Goldberg was incarcerated in a whites-only prison in Pretoria, while Mandela was sent back to Robben Island and the two didn’t meet again for nearly 30 years.

The two met through activism. Goldberg grew up in a family of activists in Cape Town and was drawn to the underground movement. Because he was a road engineer, everyone assumed he could make bombs and it became his job. Mandela had worked his way up to be a lawyer and head of the ANC Youth League. The two men, who were like chalk and cheese, stood shoulder-to-shoulder in the dock in Pretoria.

“They brought Nelson to the court in leg-irons and handcuffs and this humiliating prison house-boy’s uniform. When I bought my first suit I paid 12 guineas for it. Nelson wore tailored suites that cost 75 guineas—I’m trying to say, that this is a very elegant dresser. And he stood there in his prison uniform. Legally, he should not be handcuffed and in leg-irons before the judge because it’s prejudicial, but he was looking so elegant and very hungry. He’d been in prison on Robben Island and this very strongly built man of 45 had sunken cheeks, eyes staring a bit, but holding himself… he was not going to be brow-beaten. Impressive, very impressive. I had a slab of chocolate with me, I showed it to him… I was standing right next to him and indicating if he wanted some. I broke off a square and gave it to him, he took it in his handcuffed hands, right over his face, and there was a little sharp corner near his sunken cheeks and he sucked it, as only a prisoner who has no sweet things can enjoy. As soon as it was gone, then he asked for a bit more,” says Goldberg.

Goldberg served 22 years in prison and was escorted by police out of his own country to spend even more years in exile in London. He returned to South Africa, around 10 years ago , to advise the new government and now lives in tranquil retirement in Hout Bay, near Cape Town. Goldberg believes this retirement would not have been so peaceful if it had not been for the great man himself.

“There’s enough bitterness, there’s enough anger and resentment, had there been a real civil war in the streets we wouldn’t be where we are today, we wouldn’t be sitting at Liliesleaf. We’d be sitting in the smoking ruins of destroyed country, so Nelson Mandela with this whole background, he, Nelson Mandela taking office with this whole background of four years of negotiation and putting out the fires of the violence of the apartheid,” he says.

Loading...