You say your prayers when your kingdom comes crashing down but do you survive to tell the tale?

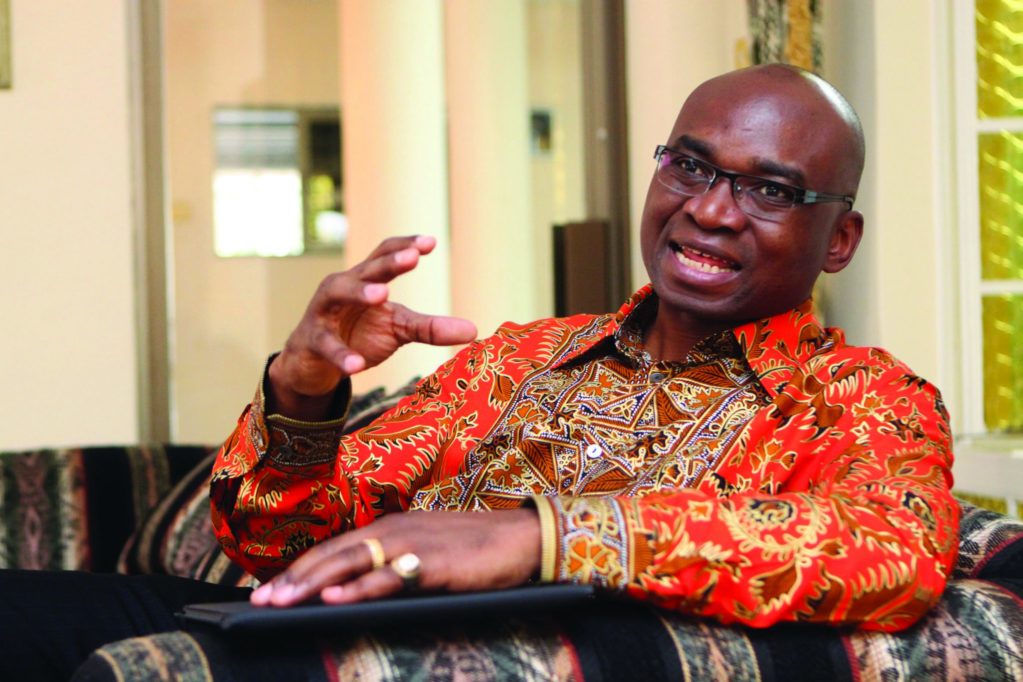

This is the story of 46-year-old Nigel Chanakira, one of the first black Africans to own and run a bank in Zimbabwe. He was only in his 20s in 1994 when he opened Kingdom Bank and Kingdom Financial Holdings. He beat the odds of an uncertain political and financial environment to make it happen. But the company has been as much his success story as it has been his worst nightmare.

Chanakira says: “I had worked in white organizations. I worked in an Anglo [American] subsidiary and I was the second black investment analyst in Zimbabwe. That is where I cut my teeth and learnt about financial markets.”

Chanakira was also among the first group of black children to go to former whites-only schools in the early 1980s.

“That was an experience of its own. I was very vocal about racism. I showed them that you can co-exist as black and white,” he says.

Loading...

Working for finance house Bard after school, he learnt to trade government bonds. He also came up against racist drivel like the notion that blacks could not be investment analysts.

“It was still a time when professionally things were quite racial. I proved them wrong because I became one of the finest investment analysts in the industry,” says Chanakira with a mock British accent.

But what drove him into setting up his bank was his passion for economics. He jokes that TV programs about the lifestyles of the rich and famous, showed that the biggest bling belonged to lawyers and bankers. This also sparked his interest.

Having already made a mark in the heart of the financial district in Zimbabwe, the 26-year-old knew he could take the next leap. He started by making the bold offer to buy and lead Bard. That was rejected. He then sought a licence to start a bank. And just like that Kingdom Bank was born.

“The idea of Kingdom as the name for the bank was born out of Matthew 6 verse 33: “Seek ye first the kingdom of God and his righteousness and all these things shall be added unto you,” quotes Chanakira, who is cut from Pentecostal cloth and peppers his speak with biblical quotes.

Kingdom became the second bank to be listed on the local bourse. USAid sponsored him on a visit to the States. The aim of the visit was to expose him to how global financial markets work and to give him insights into how the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) operates. The ultimate dream for Chanakira was to have Kingdom listed in the Big Apple one day.

By 2007, Kingdom Financial Holdings merged with Meikles Hotel, led by John Moxon, to form the powerful conglomerate, Kingdom Meikles Africa (KMAL). Meikles had been toying around with the idea of getting into a banking deal and looked to Kingdom Bank. The merger was the culmination of lengthy negotiations. It happened because Meikles wanted an empowerment partner and a bank to be part of his diversified company that included Tanganda Tea Company, Cotton Printer, TM supermarkets and stores as well as KFHL subsidiaries. Chanakira sold 25% of his shares worth, a record of, $260 million.

Chanakira’s merge deal was big news. It got the bourse all shook up and raised the prospects of a listing on the NYSE. The deal was a triumph for Chanakira in a turbulent Zimbabwe market that had seen several local banks collapse under the burden of debts, insider trading, bad loans and corporate malfeasance. At the time, analysts called the KMAL deal ‘a marriage made in heaven.

“The share price went ballistic, it hit the roof,” says Chanakira.

But the happy days would be short-lived. In one year, relations between investors soured after a furor over money invested into the Cape Grace hotel in South Africa. Chanakira was questioned about how the money had been transferred out of Zimbabwe without his knowledge and investors demanded that the money be returned.

Soon the marriage became acrimonious and the fallout, public and nasty. The demerger between Kingdom Financial Holdings and Meikles Africa followed. Shareholders agreed to demerge KFHL from Meikles on the condition that Chanakira pay Meikles around $23 million by 2010, to regain control of KFHL.

The fallout had all the ingredients of a soap opera. Chanakira admits that the manner in which his worst day played out was full of drama that only Hollywood could have improved.

Chanakira remembers it well. It was September 2010 and he had just landed at O.R. Tambo airport in Johannesburg en route to China for the World Economic Forum meeting. His reputation intact, he had been invited to be part of a global team of young, African entrepreneurs who would debate current world business trends.

As he was checking in and clearing customs, it didn’t occur to him that his KMAL partner, Moxon, wanted him out. Chanakira says it was exactly like a typical African coup d’état. The takeover was swift and stealthy, as they executed the plan while the leader was away on official business.

“I went to the airport with a ticket to China, but I ended up flying back to Harare. Just imagine, you are about to fly out to the World Economic Forum, as a young global leader, then you receive a report of a circular, informing you you’ve been fired. John Moxon, chairman of Meikles Africa, issued a letter firing me and instructing me to leave the company. I was fired via circular sent to the market,” says Chanakira.

It was the ultimate humiliation. He was hurt, irritated and drained of energy.

In that instant, it mattered little to Chanakira that he had won numerous management awards in Zimbabwe and had been named among the greatest entrepreneurs on the continent. All the hurdles he had to overcome to form Kingdom bank and to cement the deal with Meikles, seemed in vain.

“I had sold my house to start that bank and went back to stay at my father’s house,” he says.

He adds: “We built Kingdom and expanded to Malawi, South Africa and Botswana.”

But there was no time for self-pity. Once he touched down at the airport, he began to initiate a plan to reclaim his business. His plan was to rope in political empowerment groups that would fight in his corner. When ZANU-PF party officials, loyal to President Robert Mugabe, got wind of the KMAL debacle they were hopping mad. They were not about to let one of their ‘success’ stories, which was part of the government’s indigenous empowerment strategy, be gobbled up and spat out by white business.

Even though Chanakira instituted legal proceedings, it was politics that prevailed as Chanakira called in political favors. Zimbabwean media has continued to take a dim view of Chanakira’s use of politics to handle his business affairs. Moxon eventually fled to South Africa after been specified by government for allegedly “externalizing” foreign currency.

“The demerger was a very complex transaction; it had undertones and overtones of complicated business dealings, political interference, race, even greed. The political overtones were dominant,” says Dumisani Muleya, editor of The Zimbabwe Independent.

“Chanakira had his connections behind him, pro-black economic empowerment business people, your Philip Chiyangwa, Themba Mliswa, the affirmative action proponents. Moxon marshaled some political support. He also had very strong political connections. You have to see who he was working with. He was working with Farai Rwodzi, who is well connected politically. Rwodzi had the backing of the late Retired General Solomon Mujuru. That’s the nature of business in Zimbabwe,” says Muleya.

For Chanakira, it’s been about clawing back from financial disaster to rebuild his reputation.

“I have developed friendships out of the crisis. It was very difficult. When I was still at Meikles, I had hair then—it went gray in those two years,” he says, with a chuckle.

Doing business in Zimbabwe remains an unpredictable environment where policy inconsistencies agitate both domestic and foreign investors.

He says of Zimbabwe’s indigenization program: “I think indigenization, as an empowerment tool, is a great concept. Empowerment is needed, let nobody lie to us. I can’t start a bank in the US. You can’t start a TV station [or] media. There are certain industries that are guarded in the US.”

But he adds: “The policy is too strong for the season and if you bludgeon people, if you bulldoze them, it doesn’t work.”

The program driven by indigenization minister, Saviour Kasukuwere, is a real threat. Plans are for foreign banks to give up half their stake to Zimbabweans under the controversial Indigenization and Economic Empowerment Act. Already Standard Chartered, Barclays and Stanbic are in the firing line and stand to have their licences revoked.

Zimbabwe’s central bank has warned of turmoil in the financial sector, should some of these proposed government drives take place. Central bank governor, Gideon Gono, says: “There is no law that provides for arbitrariness on the part of anyone and or expropriation of banking assets in Zimbabwe yesterday, today or tomorrow.”

However, the invitation stands for Zimbabweans to come forward to start banks. Chanakira would agree, even with the rollercoaster ride he’s had. You can’t keep him from business and you can’t keep him from giving thanks in the prayer room he has in his home.

“I grew up in a very strong business family. I had a rich business culture.”

He warns about due diligence and about choosing business partners carefully.

“Kingdom is a legacy, how do you sell it for a bowl of soup, I just can’t do [that],” he says.

Chanakira lives in a posh Harare suburb today. He points to the stairs in his mansion.

“I have a prayer room upstairs; I went there to pray every day. It was three difficult years. It took nearly three years for the fight and to survive after the demerger. That was God’s intervention.”

Chanakira is still passionate about listing Kingdom on the NYSE and says it’s still a possibility.

“Absolutely, it will happen! It’s a journey. I guess we probably need another five years to get there. Africa is too rich to be poor and I want to be one of the world changers,” he says.

Kingdom Bank now has new investor on board, namely Africa Asia Bank.

Only a few months ago, Kingdom Bank was dogged by reports that they had to send clients home without cash, allegedly because the bank simply didn’t have money. Chanakira said, at the time that it was just a small hiccup and they were not having cash flow problems.

Chanakira says there’s no stopping him and that he still has a lot of his story to tell.

“I am not only going to write a book, but I’m going to make a movie. Dallas will have nothing on my story,” he says.

Loading...