Takun J and his entourage weave their way between the unfinished concrete buildings, through the sandy alleyways of Monrovia’s largest slum, West Point.

“That not small star,” a young man says, as Takun, aka the ‘King of Hipco,’ Liberia’s unique take on hip-hop, passes.

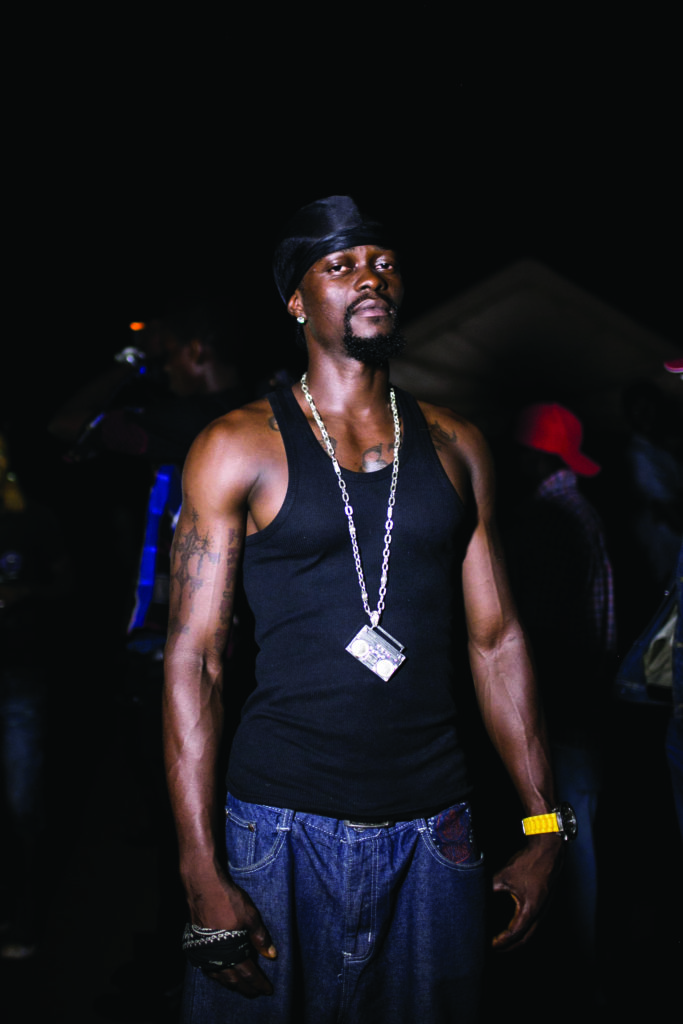

Market women, teenage girls, men, young and old, and gaggles of children trail behind the tall rapper. Wearing a cap flipped backwards and punctuated with a ‘T’ and a black tank top, bracketed by his muscular arms tattooed with the word, Hipco, and a crucifix, Takun J walks into a throng of people cheering his name.

Today, his fans have opened a chapter of Code 146, a small club the Hipco star recently set up in downtown Monrovia. Takun’s club is a place for musicians to meet, jam and perform, a rarity in a country where live music is only just emerging, a decade after the civil war.

Loading...

Back in West Point, the stage is set: a slab of concrete covered with a silver tarpaulin, a crowd barrier made of a thin piece of rope strung between two sticks and an amplifier that is heavy and scratchy. While TakunJ has established himself as Liberia’s leading rapper and now plays at small nightclubs, entertainment centers and NGO gigs, he started his career performing on makeshift stages in places like this. The people who live here, Monrovia’s masses—the ‘living-on-less-than-a-dollar-a-day’ Liberians—are whom he makes his music for and identifies with most.

“I speak to the youth: the street guys, gronna boys, thugs,” he tells me, back at the small wooden bar inside his club that is painted in Liberian colors—red, white and blue.

In Liberian English, gronna is a pejorative term meaning a person who was raised on the street and leads a life of drug abuse and crime. But TakunJ has reappropriated the word and used it to reflect the everyday hustle of young Liberians, many of who are unemployed and with uncertain futures.

“It’s the same thug life that we all go through. You suffer like a gronna person when you don’t have money, when you don’t have the support of your mother and father, that’s a thug life, that’s a gronna life,” he says.

Hipco is a mixture of rap and Liberian English—also known as colloqui—and has been around since the 1990s, but has only taken off in recent years. Colloqui is incomprehensible to outsiders, but it is a patois, a leveling language spoken across Liberia’s tribes and classes. While most sound systems across the country blast out Ghanaian and Nigerian music, Hipco has steadily been making its way across the nation’s airwaves, onto dance floors and drinking spots and the little boom boxes of motor taxis or pehn-pehn boys.

The rapper was born with the name Jonathan Koffa but dubbed himself Takun J because he sees himself as one of the founding fathers, or pioneers of this music form.

“It’s not the T-Y-C-O-O-N, no it’s not that business tycoon Takun in our own vernacular means big brother, a giant, a strong person who been into something for a long time,” he says.

Hipco is political in nature and often critical of Liberia’s ruling establishment. Takun arrived on the Liberian music scene back in 2005, with a tune attacking the transitional government of Gyude Bryant that was accused of graft. The song titled ‘We’ll Spay You,’ meaning ‘we will expose all of your dirty deeds,’ echoed throughout the streets of a shell-shocked Monrovia. ‘Police Man,’ which spoke about police corruption and brutality, was his next big hit and landed him a beating at the hands of the Liberian National Police before a gig. Most recently he became Liberia’s anti-rape ambassador. During his performances he splices in songs condemning violence against women.

One of his biggest hits, ‘The Pot Boiling Remix’, a song about hardship and scarcity that uses a Liberian saying—‘my pot can’t boil’—has become an anthem throughout the city.

Everybody pot boiling, my pot can’t boil.

The only time my pot can boil when a car kill the dog.

The government breaking, so the youth is still jerking.

School fees got me sent from school cuz my pot not boiling.

Corruption in the city got me kicking some dust cuz my pot not boiling.

Tita Nagbe, a 20-year-old fruit seller, with a pretty round face, stands barefoot on a grave in the middle of the yard with a group of women and listens to the performance.

“I like his singing, he is active. His music is fair; everything he says is true,” she claims.

For Jacob Weah, a 25-year-old tailor, the appeal of Takun J’s music is its themes and messages.

“He delivers a lot of messages and says that we should believe in ourselves,” Weah tells me as he leans up against a wall dressed in flip-flops and a Real Madrid soccer kit. “He sings about oppression we suffer in our society; we are not receiving our basic needs.”

The lack of an established music industry in Liberia makes it difficult for artists to make money, says Takun J’s manager Nora Rahimian. Unlike neighboring Ghana or Nigeria, there are no production teams, just small studios or spaces where artists can record their tracks on old equipment and collaborate with engineers. With slow internet speeds, Hipco artists have limited possibilities for expanding their audiences beyond Liberia’s borders. As a consequence, Takun J’s music has had limited play outside of the country, and can be heard in a few clubs in neighboring Sierra Leone, Ivory Coast and Ghana.

Music piracy and lack of legal protection poses the greatest challenge for Liberian musicians, making it difficult even for artists as well known as Takun J to make money. But for now Rahimian says piracy is a positive thing.

“At this point, piracy is great. We will encourage the gronna boys—take the song and pirate the song because there is no other way to distribute the song. Let music reach the people. It’s not about being exclusive… If you can afford to pay for it pay for it.”

Despite the challenges, thousands showed up to the first Hipco music festival held last October, with another to be held this December. Takun J will be touring West Africa and then the United States.

Back at Code 146 on Carey Street, we talk about the future of his career and the future of Hipco in Liberia. The bar is set in a sand pit under a zinc roof, with a pool table, mixing deck and flat-screen TV mounted in the corner. In front of the small concrete stage is a weight bench alongside a bar with heavy metal axels attached on either side. It is rainy season and the stage is slicked wet, but come summer, Takun J expects the place to be packed.

While being a musician in Liberia is a hustle, Takun J is optimistic about the future. ‘God Sent’ is tattooed across his chest.

“I believe that I was sent to carry on this mission and I believe that God sent me to accomplish this mission.”

The mission: to take Hipco to audiences outside of Liberia.

“We are fighting a revolution now. Hipco will take the world,” Takun declares. FL

Loading...