When the battle against the Portuguese ended, Samora Machel was aware of the importance of image. The first Mozambican president saw strategic power in film and how it helped him promote national unity. His government established the National Institution of Audiovisual and Cinema (INAC), one of its first cultural initiatives, in 1976. It produced more than 300 documentaries the following decade, in an initiative dubbed Kuxa Kanema, which showed how the newborn nation took its first steps. With Machel’s death in 1986, and Mozambique’s turn towards the West, the small industry almost became extinct.

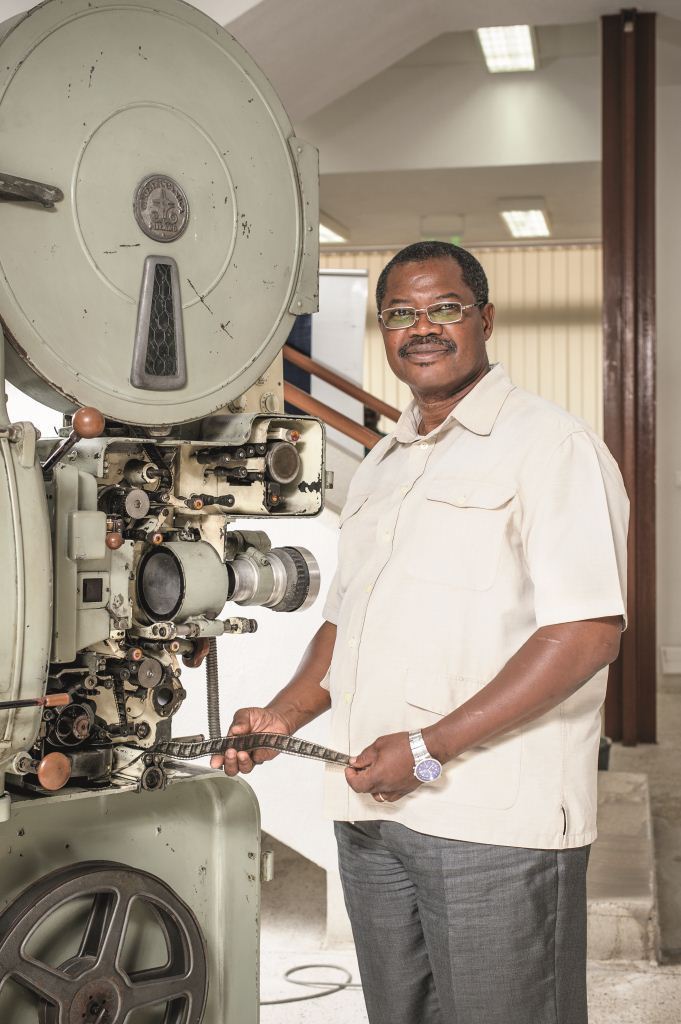

“It is true that there was a decline, especially when the country opened up to the market economy with the arrival of the IMF,” says Djalma Lourenço, director of INAC.

Producers began to emerge in Maputo due to private initiatives. The production of documentaries and advertisements for the innumerable NGOs that work in the country are their bread and butter. While short films are emerging, nobody dares speak of a Mozambican film industry.

“An industry presupposes a value chain, that we yet to have in Mozambique,” says João Ribeiro, director of The Last Flight of the Flamingo, which premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2010.

Loading...

Cinematic legislation forces international producers to establish partnerships with local producers, who are often unable to survive on their artistic ambitions.

“The fundamental structure of a Mozambican producer is to produce institutional documentaries and advertisements in order to fundraise to be able to produce their own work,” says Renato Chagas, a Portuguese director, who moved to Mozambique six years ago during the country’s boom years due to American and European investments.

In April 2006, Maputo was brought to a standstill with the filming of Blood Diamond, directed by Edward Zwick. The film, which starred Leonardo DiCaprio, had an estimated budget of $100 million, according to IMDb.

“In four months, eight million dollars was spent in Mozambique in hard cash. Just downtown, in the capital, a million was spent on renting out stores and closing down streets,” says Ribeiro, who worked as executive director on the film.

Yet, the millions Hollywood brought to Mozambique had a perverse effect. The costs of production elevated exponentially once local authorities, such as the Maputo municipality, grossly increased the prices of road rental. Mozambican producers are also all too familiar with excessive bureaucracy as a result.

“Filming in Mozambique is a headache. Before we begin filming, we have to fulfill a series of requirements with the different organizations, like INAC or the Ministry of Interior,” says producer Mickey Fonseca.

“Mozambique is not film friendly,” added his colleague Pipas Forjaz.

The two men, who have won numerous international awards for their documentaries, established a production company, Mahla Filmes, in 2009. Both were recently involved in the production of Caught in a Flight, by Oliver Hirschbiegel. Due to Mozambique’s appeal to cinematographers, the biographical film, which cost $32 million, lends its landscapes to Angola to tell the story of Princess Diana’s final years.

“We have a unique reality: architecture from the ’50s and ’60s that, still today, is hard to find in other cities. Furthermore, we have virgin landscapes and social stability,” says Ribeiro.

The Mozambican Law of Cinema, which will be voted on this year, continues to lack consensus. According to INAC, Mozambique produces around 25 works, either documentaries or films, annually. Finding a way to bring long-term sustainability to these productions is the key to creating a Mozambican film industry. But, how to achieve it?

Mônica Monteiro of Cinevideo, a Brazilian production company with an annual profit of nearly $23 million, says that Mozambique is a commercial bridge for the rest of Africa because it caters for the Lusophone market, which has close to 250 million speakers. Cinevideo’s aims are to produce films that allow consumers to identify with Mozambican productions. She believes that financing should be sought in Europe.

“The Old World consumes lots of Africa, as a result of their historic relationship.”

A taste of the money available from Europe is the program ACP Cultures+, which is destined to cultural sectors in countries in Africa, the Caribbean and the Pacific, to the value of €30 million ($40 million). Funds are available until 2013, but with the current financial crisis in the Old World, it is at the brink of extinction, unless someone puts in some legwork, and quick, the diamond could lose its luster. FL

Loading...