In silence and solitude we traverse the scrub-specked grasslands of Kenya’s famed Masai Mara in search of an elusive leopard spotted the previous day.

The rains have begun and newly formed rivers and gorges pockmark a terrain sketched with the region’s emblematic acacia trees. Shuka-clad Masai tend cattle on conservancy land fringing the national reserve and copious wildlife blankets the expanse. But few of the roughly 700,000 tourists who descend annually upon one of the Seven New Wonders of the Natural World remain. Soon, shuttered camps will reopen and from July through October crowds will return to witness the Great Migration of countless wildebeest, zebra and other game transiting from Tanzania’s adjoining Serengeti National Park.

Navigating the muddy soil, even in a tank-like vehicle, proves challenging. But perseverance rewards us with remarkable sights. A buoyant Thompson Gazelle inexplicably chases a rare Denham’s bustard, lions feast on zebra remnants, the carcass of a newly killed giraffe sadly succumbs to scavengers, while herds of majestic elephants lumber across the plains. Bones and skulls litter the landscape, but rebirth abounds. An endangered cheetah lounges amid camouflaging scrub just meters from her two young cubs. Babies of every endemic breed suckle their mothers’ teats as siblings frolic nearby. It’s the natural order of things and I feel privileged to behold this diverse kingdom without mobs encroaching.

Unfortunately, serenity masks peril as escalating human-animal conflict and an ivory poaching pandemic threatens survival of the animals we come to see.

Loading...

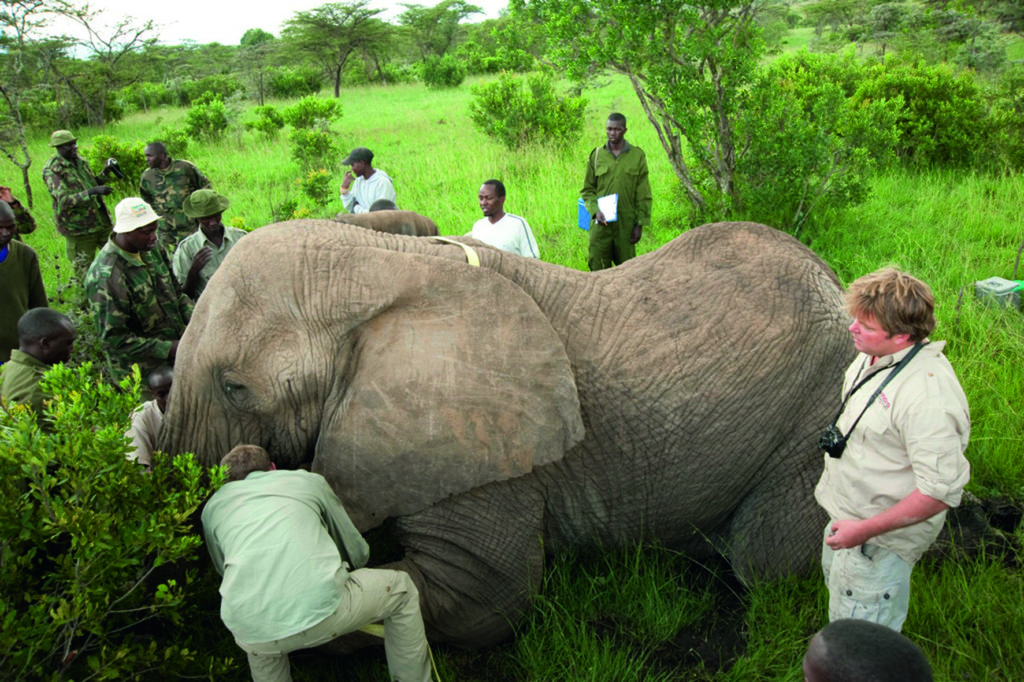

Enter the crusaders, one of whom is Kenyan native Richard Roberts, founder of The Mara Elephant Project (MEP). It works alongside government and environmental groups—including the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS), American-based Escape Foundation and prominent NGO Save The Elephants. The privately funded non-profit organization was created in 2011 to help communities “combat the increasing human-animal discord” and augment anti-poaching efforts. In 2012, the Mara suffered 149 elephant mortalities, 139 of those attributed to poaching.

“Too many elephants were getting killed. Something needed to be done to help farmers and wildlife coexist Without wildlife there is no tourism… and tourism is wildlife’s savior. There are more eyes on the ground and more incentive to protect the animals,” says Roberts. And as the tourist industry accounts for 14 percent of Kenya’s GDP, raking in $1.2 billion in 2011, that’s a lot of incentive to keep visitors coming.

“A funny disconnect exists. The Masai love tourism but don’t like the wildlife. They don’t see the correlation,” adds Marc Goss, director of MEP and manager of Mara North Conservancy.

But that’s not a universal sentiment, especially amongst the more than 100 Masai, who have thus far benefited from sponsored training at the Mara’s Rekero Camp guide school. For them, the dual crisis is evident as I learn from Teketi “Stephen” Nabala, my ardently well-informed guide from the exclusive Ngerende Island Lodge.

“We [Masai] benefit greatly from tourism, economically and socially. Exposure to more people and increased education is beginning to open eyes to the importance of protecting our ecosystem.”

Recent demonstrations in the Mara calling for stronger government action substantiate changing attitudes.

Since the reserve opened in 1948 on a scant 520 kilometers—today park and conservancy land spans more than 1,500km2—tourism has exploded. The Masai Mara alone generates $50 million annually. In the mid-nineties, privately-managed conservancies sprouted on the reserve’s perimeters when Masai began leasing newly-owned parcels of formerly communal land to lodge operators. This arrangement provides income, employment and camp-endorsed community support for residents, while visitor fees ($70 to $100 for non-East African residents) subsidize Conservancy management and preservation efforts.

But it’s a precarious balancing act. Animals don’t recognize boundaries and often venture outside protected areas. In the past two years, farmers increasingly greet encroaching elephants with violence, while the acute resurgence of poaching continues unabated. These are complex and convoluted issues stemming from Kenya’s ballooning population (up from seven to 43 million since 1963), traditional pastoralist Masai culture embracing agriculture, limited arable land and the revitalized, highly profitable, high-demand illegal ivory trade.

Although the MEP collars and monitors Mara elephants, maintains a network of paid informants and two roving general security teams, “our resources are insufficient,” says Roberts.

Hoping to secure an airplane and additional security teams this year, it all comes down to funding.

“We’re seeing that poachers are becoming more organized and lethal, further emphasizing the need to expand MEP,” Goss interjects.

“The good news is that the KWS has many dedicated employees with whom we share information and resources. Kenya is very lucky to have one central wildlife service, which eliminates the kind of bureaucracy Tanzania has,” says Roberts.

Further encouragement derives from the new constitution that empowers the county rather than local government to oversee the Mara.

“We’re hopeful that things will improve with decentralization and the recent election of Narok County Governor Samuel Tunai. If all private sector revenue coming from Narok was used in a transparent manner it would be the third richest county in Kenya. If that money was used sustainably, we would solve a lot of these issues,” says Goss.

“In the past, administrators ignored anything going on outside their boundaries,” notes Ol Chorro Conservancy Manager James Hardy.

“Everyone is now realizing that we’re in this together and that one region’s problems ultimately affect and belong to all [regions]. We’ve recently established a conservancies forum to address issues and voice concerns on a national level.”

It’s Roberts’ birthday and he’s invited a few friends to celebrate. Pouring rain, snorting hippos and the menacing yelps of hyenas provide the soundtrack. Yet even in the relaxed ambiance of Roberts’ tented camp, conversation turns serious. Will the newly decentralized government be as effective as hoped? Will education help mitigate the human-animal and poaching crises? Will national reserve and conservancy entrance fees get to the right places and be used efficiently?

Before returning to my tent, I’m treated to a bedtime story that hinders any chance of peaceful sleep. It’s the tale of a huge and beloved Mara elephant named Heritage, who, although collared, had twice been wounded and treated for farmer-inflicted injuries. “We thought this elephant was blessed with a cat’s nine lives. Then a few weeks ago he was poached,” Goss laments, clearly taking it personally.

Heritage’s death adds yet another to the toll of seven mutilated bulls discovered in Mara West last December. Since January, 74 elephants have been slaughtered in Kenya. In 2012, a reported 656 elephants were killed (149 in the Mara), up from 578 in 2011. Samburu and Tsavo National Parks are especially vulnerable, the latter having lost 12 elephants, including a two-month-old calf, in March. In total, wildlife organization Born Free estimates that more than 32,000 elephants have been killed since the beginning of 2012.

Fueled by an insatiable Asian appetite for ivory, particularly amongst China’s newly affluent, the “shifta” with suspected links to Al-Qaeda, as some speculate, through Al-Shabaab in neighboring Somalia, are infiltrating Kenya in record numbers. With a kilogram of ivory fetching up to $2,000, this illicit industry nets an estimated $7 billion annually.

Most illegal large-scale ivory seizures over the last three years have originated in Kenya and Tanzania, which, alongside Uganda and five Asian nations were targeted at the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) conference in March for failing to adequately crack down on the ivory trade.

The good guys face tough odds as organized cartels, allegedly unscrupulous officials and outdated Kenyan laws that impose absurdly tame poaching penalties, conspire against them.

That said, notwithstanding a recent poor track record, Kenya has long been at the forefront of wildlife conservation. One of the first African countries to ban trophy hunting in 1973, Kenya vehemently opposed the CITES edict permitting China to purchase non–poached ivory and is currently countering Tanzania’s attempt to remove elephants from the endangered species list. To date, Kenya has allied with 16 African nations (two-thirds of the 23 member African Elephants Coalition) to quash the proposal that will repave the way for legal ivory sales.

Despite international outcry and support, officials and NGOs in Kenya and throughout Africa are fighting an uphill battle. A CITES report last June documented the highest African poaching numbers in a decade and the most ivory seizures recorded since 1989. The contraband ivory trade has more than doubled globally since 2007 and is three times larger than in 1998.

“The new wave of killing elephants in Africa is in many ways far graver than the crisis of the 1970s and 1980s… there are fewer elephants and demand is far higher. Record ivory prices in the Far East are fueling poachers, organized crime and political instability across the African elephant range and the situation shows no sign of calming,” wrote Save The Elephants founder Iain Douglas-Hamilton in the January-March issue of conservation journal SWARA.

Like most visitors, I journeyed to the Mara in pursuit of spotting big game. But, I depart with something far more indelible than beautiful photos, muddy shoes and Masai beaded jewelry. I take with me a profound awareness and renewed appreciation for the consequences of human infringement on our fragile planet. And a fierce desire to do s

Loading...