What secrets does a city hold within its bosom? In Johannesburg, one of them is an intriguing

labyrinth of tunnels that once served as a postal delivery system. Could such relics of the past be the subterranean realms of the future? Urban planning points to what is now called ‘hypogeal cities’.

Johannesburg’s central business district (CBD) holds a secret within its deep, dark belly.

On the surface are the citadels of power housing some of Africa’s oldest and biggest corporate institutions.

Beneath this morass of steel and concrete, is a labyrinth of tunnels few know of.

Loading...

We search for them, walking miles in the sun, scouring the grimy innards and alleys of a business district that was once seen and filmed by Hollywood producers as a Manhattan ‘lookalike’.

These streets have been witness to searing political upheaval and mass unrest, and bear the scars of a brutal apartheid past.

But every city needs daily witnesses in its account of the here and now, and you find them on the streets – the shopkeepers, traders, commuters and the security guards who watch the CBD change color and character from morning to night.

And sometimes, the best leads come from these purveyors of change, the ordinary people who witness the city up close every day.

The entrance to one of the tunnels which run 3km in total under Johannesburg.

And luckily, we find ours – the security guard who will indirectly lead us to the tunnels.

“Yes, I have been inside these underground tunnels,” he says, reluctant to reveal his name or tell us more. He relents, however, and gives us a number we can call, that of the site manager of what he calls “the Post Office tunnels”.

With his help, on a sultry October morning, we arrive at the Old Johannesburg Post Office on Jeppe Street, a street lined with shops and informal traders selling everything from cell phones to socks.

Business here has a life and rhythm of its own, oblivious to what lies beneath.

“I have been living and working here for 30 years and I have never heard of what you are talking about,” shrugs Givemore Sithole, a worker in the area, when we ask if he knows about them.

But history and fact co-exist.

According to an 80-year-old report simply known as “the heritage report”, the tunnels were built in October 1935, at the height of apartheid, for the effective delivery of mail between the Post Office and Park Station, about 2km apart.

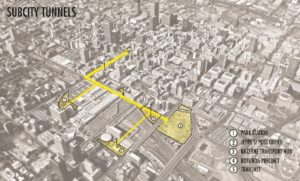

The tunnels also connect to Gandhi Square at its other end, and in total, are 3kms-long.

“This tunnel was built at a time when more and more people were coming to Johannesburg to look for work in the City of Gold. There was a lot of congestion on the roads and they created this big ‘machine’, which I hear even connects to Gandhi Square, which is about another 1.2 kilometers away,” says Johan Visser, a site manager at the

Africa Housing Company, which is redeveloping the Old Johannesburg Post Office.

Johan Visser. Photo by Motlabana Monnakgotla.

Before we meet him, we run into a real estate agent, who is currently leasing space at the site of the old post office. We ask if she knows about the history of the building – how was she pitching the property to prospective clients? Did she know about the tunnels?

“I can’t believe there are tunnels here. I have never even heard of them but I think people would appreciate this place more if they did,” she tells us, not wanting to be named.

Even the construction laborers working on the post office site are unaware.

Visser takes us to the tunnels. We find the entrance, with the help of his colleagues, and it’s wide enough to fit a small car.

It has a large red metal door, with access temporarily blocked by bulky construction material.

The workers manage to clear the entry and open the door. Inside the tunnel, it’s like a big black hole – it’s pitch-black but holding within its bowels an old secret.

“Beware of rodents and snakes in there,” warns Visser, as we gingerly step in.

Through this tunnel, according to the heritage report, estimates are that 900 bags of mail were conveyed on wheelbarrows and sifted per hour at each end. They also had rudimentary versions of the conveyor belts of today.

The tunnels were shut down in 1956 for reasons not known, abandoned and forgotten, until about two years ago when they were rediscovered by Ray Harli, an architect and Director at UrbanSoup Architects and Urban Designers.

We meet him at the post office end of the tunnel, but he recounts how he stumbled upon the Park Station side of it – and the intriguing network he discovered under the surface.

Underground construction in the 1930s

Work progresses at the Old Johannesburg Post Office. Photo by Motlabana Monnakgotla.

“We are constructing a very large transport hub in Newtown [part of Johannesburg’s inner city]. While we were excavating, we came across an opening. We weren’t sure what it was and when we went inside, we discovered the tunnel, and realized it goes deep. Finding the tunnels felt like a treasure hunt. It was also partially scary because it was very dark inside. We didn’t go in deep that day and went back a few weeks later with a full team. We walked inside for over a kilometer. There was water inside and we had to turn back when the water was too high,” says Harli.

About 6,000 kilometers away in Egypt, almost a century ago, one can almost imagine the euphoria that must have accompanied Howard Carter’s discovery of the chambers that led to King Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

But Harli was pragmatic; soon after the discovery, he went straight to his office and contacted the Department of Heritage to learn more about the subterranean discovery.

Ray Harli, Architect. Photo By Motlabana Monnakgotla.

While the tunnels were operated by the post office, they were constructed by the workers who built the railroads of the time. It’s a fact revealed by Anne Benson, whose grandfather, William Pryce-Rosser, she says, designed the tunnels.

“We have a whole album of photos of the tunnels being built. My grandfather used to tell us the tunnels were there and he had worked on them. He was involved in a lot of work at the time and he was very proud of them,” says Benson. The pictures she has of the tunnel being constructed are indeed rare.

She also shares with us the typed-out ‘thank you letter’ her grandfather received in 1934 from the ‘Town Clerk’s Department’.

The tunnels cost a fortune in their day. For example, according to the yellowing heritage report referred to earlier, it cost a whopping £170,000 at the time and used 15,750 tons of concrete. There was also a section of the tunnel called ‘parcels and baggage’, which was 914 metres long and cost £71,000 to build; and then a section called ‘signals’, which was 640 meters long.

“The city didn’t know about the tunnels, but the Department of Heritage did,” says Harli.

Since learning about them, Harli has been looking into how these tunnels can be best put to use.

“Now, people call me ‘Mr Tunnels’,” he laughs.

“A year before we found these tunnels, I was in New York and they have an underground tunnel that they have converted into what they call the world’s first underground park. They cut holes on the pavement up above to let light inside. They even have trees underground,” says Harli.

Inspired, he hopes the Johannesburg tunnels could be commercialized too.

“The world is moving in very interesting directions and we can use places like this that already exist for underground developments. For example, the idea is to link Park Station with our transport facility in Newtown so that there is a direct pedestrian link underground. Having this direct link will bring connectivity between different transport hubs. A more ambitious plan would be to build a commercial retail space with coffee shops and art exhibitions,” Harli says of his plans.

According to him, with the right type of management, this could become a destination space. He offers the example of the city’s stylish Maboneng Precinct, which had been abandoned but was revamped and turned into a key tourist destination featuring food markets and art galleries.

“People desperately want [options]. Changing this up can be a very good opportunity which will also preserve the heritage,” says Harli, calling the potential development “a sub city”.

Harli adds that the problem with the Johannesburg tunnels is that there is no agreement on who owns them.

He says he would need about R30 million ($2 million) to turn them into “a heritage shrine” where people can enjoy them as green, public spaces.

“It is also hard to convince government to spend on this type of development because there are some major problems in the inner city. Some people could argue a space like this is a ‘nice to have’ but our argument is that it is something that could be commercialized,” says Harli, who is considering a few rounds of crowdfunding to kick-start the project.

“I have told the city about what we would like to do but we need to find out who definitively owns the tunnels.”

The ownership is unclear, and this is a fact reiterated by a contact we meet at the Johannesburg Development Agency, which is the city’s real estate developer.

READ MORE: The Brain of Africa more of an artist than an architect

Harli wants to get down to business at the tunnels, but Africa Housing Company, which owns the Old Johannesburg Post Office, has plans to fix the building and turn it into apartments and commercial shops.

“There is a lot of history here. We are turning the place into shops and apartments while keeping its history. We restore and repair, but most of the things are still here. The only problem is that when the building was abandoned, there were dwellers living here who took some of the things, like all the brass and copper wires,” says Visser, showing us the granite table at the reception that is still in the same spot as it was at the old post office.

Africa Housing Company has retained the windows, murals, the clock, telegram booths, doors, ceilings and stairs, adhering to the old look and feel.

“This is a historic building, so we have to keep as much as we can as is,” says Visser, showing us some of the over 200 apartments now built where the old post office was.

At Gandhi Square, which is said to have yet another entrance into the tunnels, there is already some commercial activity underground.

An entrepreneur, Gerald Garner, owns Zwipi, an underground bar here, which was once an old bank vault with safety boxes. He also owns JoburgPlaces, which offers walking tours. Garner has been offering inner-city walking tours since 2011.

Gerald Mandevhana. Photo provided.

“Since it is such a historic building, it made sense to open a restaurant-bar in the old bank vault. We also do most of our walking tours through this space and host safaris and secret underground dinners here.”

It just points to the fact that such areas can be re-conceptualized and commissioned back to life.

WILL UNDERGROUND RESIDENCES WORK?

According to Namibia-based architect Gerald Mandevhana, many countries like Finland and China have even gone further, with concepts like underground homes.

According to Mandevhana, Mexico City even proposed an ‘earthscraper concept’, a 75-storey pyramid going 300 meters into the ground to accommodate about 100,000 people, and Singapore built a subterranean oil storage facility that goes down 100 meters.

Mandevhana says the idea of underground living is not as far-fetched as we may think.

African people have lived underground for centuries, he says.

“Two hundred thousand years back, some of the homosapiens led troglodyte lives in caves in South Africa.”

However, Mandevhana acknowledges a lot has changed in the last 200 millennia and today, the prospect of underground living has to come with readjustments to suit modern lives.

“On an infrastructure level, I believe we can actually implement the move. The architecture, engineering and construction industry in Africa is quite advanced now and several avant-garde practices and technologies are already being implemented,” he says.

However, at a systems level, he says the world has a long way to go because cities are complex organisms.

“Many concepts have been pushed up to define and idealize cities; central place theory, garden city movement, radiant city, city beautiful movement, broadacre city, right up to today’s smart cities with artificial intelligence and deep learning systems at the heart of things. As complex socio-technical organisms, all systems will need to be reviewed to ensure they optimize interactions between people, technology and the new hypogeal environment. Our systems are not yet ready for urban scale shifts towards subterranean life,” he says.

Harli and Mandevhana both see the potential of commercial spaces underground.

But Harli too is of the opinion that, in Africa, underground housing may be difficult to implement.

“You cannot justify building accommodation underground right now in Johannesburg when there are many abandoned buildings. I understand in China, where space is a problem. I don’t see residences underground but rather underground public space with commercial spaces,” says Harli, adding that building underground will always be a more expensive proposition than construction above the ground.

“For example, building an underground parking structure is five times the cost of building one above the ground,’ he says.

Deon Du Plessis, Function Manager, Urban Development, at SMEC, a multi-disciplinary engineering and infrastructure solutions company, agrees.

Deon Du Plessis. Photo provided.

“It costs more to drill down the ground. We also still have a lot of land that we can build on in Africa. From a health and safety point of view, it will also be a challenge because you need ventilation and fire protection down there, for instance,” says Du Plessis.

Mandevhana says that building underground has higher initial costs but says there are anticipated lower-running costs as well, which implies “a less-costly lifecycle” compared to surface developments.

“The negative is that, currently, the resale value of these homes is quite low, as prospective buyers avoid them due to their unconventional nature. At an urban scale, the amount of earth that will need to be removed to create volumes for the developments will be something to think about,” says Mandevhana.

There are ups and downs to several of these hypotheses.

Science informs us that underground developments will not need costly heating and cooling systems due to the thermophysical properties of the earth; they could be used as shelter from adverse weather; and would require little, if any, exterior maintenance.

Another big question or concern is that of food supply underground. Would we be able to grow food underground?

Mandevhana has some answers.

- SubCity Tunnels Concept Map

- An artists’ impression of how the entrance to the underground tunnels could look.

“Due to similar conditions between underground spaces and greenhouses, it’s possible to grow the same types of food that we grow on the surface, but again, there is an opportunity to use the surface for agricultural purposes, afforestation and reforestation to reverse global warming, for instance,” he says.

Based on questions that have arisen from the recently-unearthed ancient Turkish city of Nevşehir, perhaps an even bigger concern is if humans will be able to physically and psychologically adapt to life underground.

“The generalizations about these factors affect the applicability of hypogeal cities. Sensory deprivation is one such factor, people are stimulated by their surrounding environment, and this becomes critical in small, enclosed spaces. On the physiological side, the challenges are associated with lack of natural light, indoor air quality, high humidity levels underground, and even lack of noise,” says Mandevhana.

It means the fundamental principles of urban design and urban planning will need to be redefined, the role of the urbanist and the architect will need to be clarified and the engineering field will need to establish relevant innovations to provide appropriate solutions if we are to go the underground mass residential route in Africa.

Du Plessis thinks the first priority is to fix the infrastructure problems we have now, before exploring underground options. “Our cities are growing at such a rapid rate that we can’t keep doing what we are doing. It is not sustainable. Our biggest opportunity is to revitalize Hillbrow and the central business district,” he says.

His first call is to build more compact cities that are taller.

“The trick is to provide urban spaces that actually work. You don’t just need a roof over your head but you need to be safe, be able to work, for children to be able to play in the park and having attractive spaces. It is a much bigger social construct that needs to be addressed. We need to build much closer to where we work,” he says.

Du Plessis thinks underground developments, like the Johannesburg tunnels, can best be used to provide better transport routes for people to get to work faster.

Be it for commercial space, housing or transportation, it seems these old tunnels have triggered a new debate that may change the way we live. Forever.

Loading...