It is a century since Nelson Mandela came kicking and screaming into a world that he would change.

In one hundred years, his name has been spoken with pride from the paddy fields of Vietnam, through the savannahs of Africa to the smoky steak houses of New York. His legacy appears more contested with every passing year.

I was fortunate to have a front row seat in the Mandela years and saw the power, humour and anger of the man. I used to feel 10 feet tall at press conferences when he used to greet my questions with: “Mr Bishop, how are you?” Once I was walking to a TV interview with him, at an African Union summit in Harare, the day after I had ruptured my knee playing football, he noticed I was hobbling far behind – something he was not used to. He turned and inquired of the cause of my pain.

“May I suggest you take up boxing, it’s safer!” says the old man with that million dollar smile. I shall take the warmth of that smile to my grave.

Make it clear, I am no Mandela worshipper. He was no saint and certainly didn’t want to be one: he could be angry and petulant with the best of them; his past was chequered by domestic troubles; a man of the people, yet distant from his own family, according to many close to him. A man who promoted press freedom, yet like many of the lesser politicians who followed him, wanted his picture on every page of the morning newspaper. Mandela drew the line at the sports page – he joked that he didn’t want to risk being associated with losers.

Loading...

The greatest fear Mandela had was that his ideals – not his name – would be forgotten after his death. Not for Mandela the greed of rule, nor the trappings of power.

Yet it is very fashionable these days to run Mandela down as something akin to a sell-out. Those who claim, erroneously, that Mandela sold out his people. They say he didn’t stop poverty overnight nor right the wrongs of the past with the wave of his wand. They need to talk to those who were there in the negotiations for a new free South Africa.

“People say we gave up too much in negotiations yet we had nothing to start with,” Denis Goldberg, a man who faced death with Mandela at the Rivonia Trial in 1964, once told me.

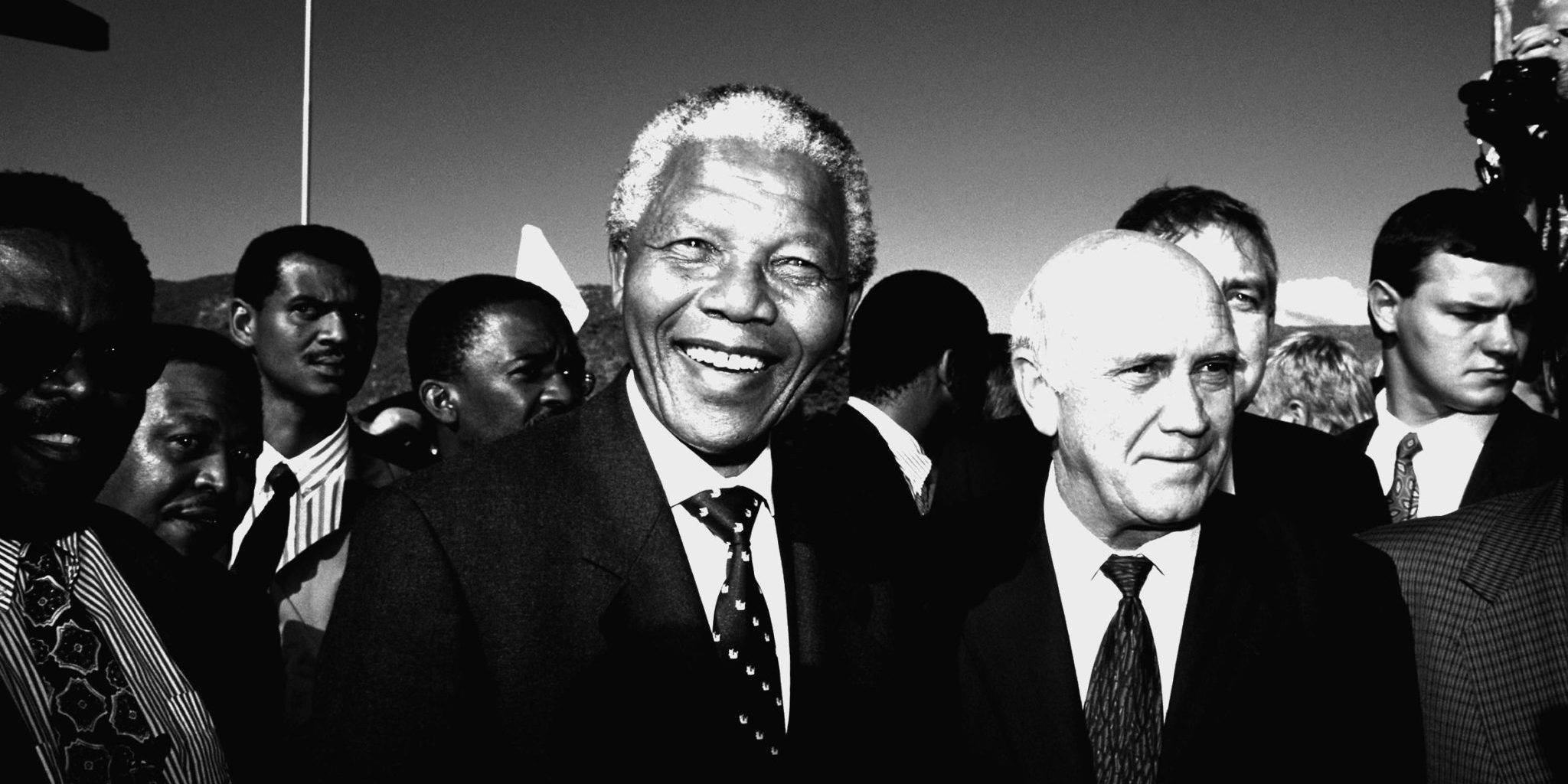

The negotiations with an entrenched elite – that held most of the cards and only grudgingly acknowledged Mandela and his comrades – were difficult to say the least. Mandela’s African National Congress (ANC) could not even threaten to go back to war because the depleting arms of its military wing posed little or no threat to the state.

Even so, a deal was hammered together somehow. In the next two years, in the run-up to the 1994 elections, Mandela won his leadership spurs as he steered South Africa away from the civil war that many feared was inevitable. He flew to Durban and told bloody-thirsty faction fighters to throw their weapons into the sea and they listened. When revered freedom fighter Chris Hani was gunned down on his front drive, in 1993, many were ready to take the law into their own hands.

Mandela barged into the SABC studios in Johannesburg that night and made a broadcast to the nation to calm down and put its weapons away. He wasn’t even in Parliament then and I wonder to this day how many lives that broadcast saved with this canny display of leadership.

Then, when into power with a virtually bankrupt Treasury, Mandela steered the National Development Programme that built millions of homes and schools; electrified the homes of legions of poor people and rolled out roads to connect the nation. Yet, the money was never going to stretch far enough and millions still have no roof over their heads and too many schoolchildren attend classes under trees.

It is fashionable these days to say the majority of South Africa must rise in a civil war in which the nation will be cleansed of its past, restored of its land on the path to righteousness. It probably sounds even better after a few drinks.

READ MORE: Celebrating Mandela From Where It All Began; Soweto

I say this is bunkum and anyone who has ever seen or smelt a civil war will agree with me. How a vile, stinking trail of dead fathers, raped women and children, destruction and disorder, can lead a country to the light beats me. Those who scream for war have clearly never seen it.

The first time I clapped eyes on the great man, at the Harare Agricultural Show, on his first foreign visit to Zimbabwe in August 1994, he walked alone, without a security man in sight. I didn’t ask for a selfie – they didn’t exist then, anyway – I was tongue-tied. We merely smiled at each other in passing.

So when people in political circles told me that South Africa’s new president Cyril Ramaphosa didn’t care for wealth and power – he merely wanted to put his name up there with Mandela – I smiled like I did on that August day in Harare.

This does seem feasible as President Ramaphosa – a millionaire in his own right – was the man who stood next to Mandela, holding the microphone, on the town hall steps in Cape Town, on February 11 1990, during his famous address on release from 27 years in prison.

“I stand here before you not as a prophet but as a humble servant of you, the people,” said Mandela to deafening cheers on that bright summer’s day.

Clearly this humility and willingness to serve rubbed off on President Ramaphosa on that fateful day in 1990. In his first 100 days, he has made manful attempts to stop the rot in South Africa by merely enforcing the rule of law. A course of action he made no secret of even before he took power on February 15.

“There are no holy cows. Anyone who is caught doing wrong things will end up behind the bars of a jail,” says Ramaphosa, with microphone in hand and humble service in mind at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, in January.

True to his word, Ramaphosa cut swathes through the corruption of the past. Former president Jacob Zuma ended up in the dock on corruption charges something that many – including me – thought they would never see in their lifetime. He removed the rookie finance minister Malusi Gigaba and replaced him with the people’s choice Nhanlha Nene who has staved off more downgrades of the economy. A clean-up of the state-owned enterprises and the institutions is underway and many who thought they were invincible six months ago have been cut down to size.

I am sure the old man, who must have been spinning in his grave over the last few years, would approve.

“Never, never and never again shall it be that this beautiful land will again experience the oppression of one by another,” says Mandela at his inauguration at the Union Buildings in Pretoria.

As we mark 100 years since his birth, it is time for cool heads and clear thinking to make sure this utopian ideal of liberty and tolerance lives on after his death. Our grandchildren will judge us harshly if we don’t.

Loading...