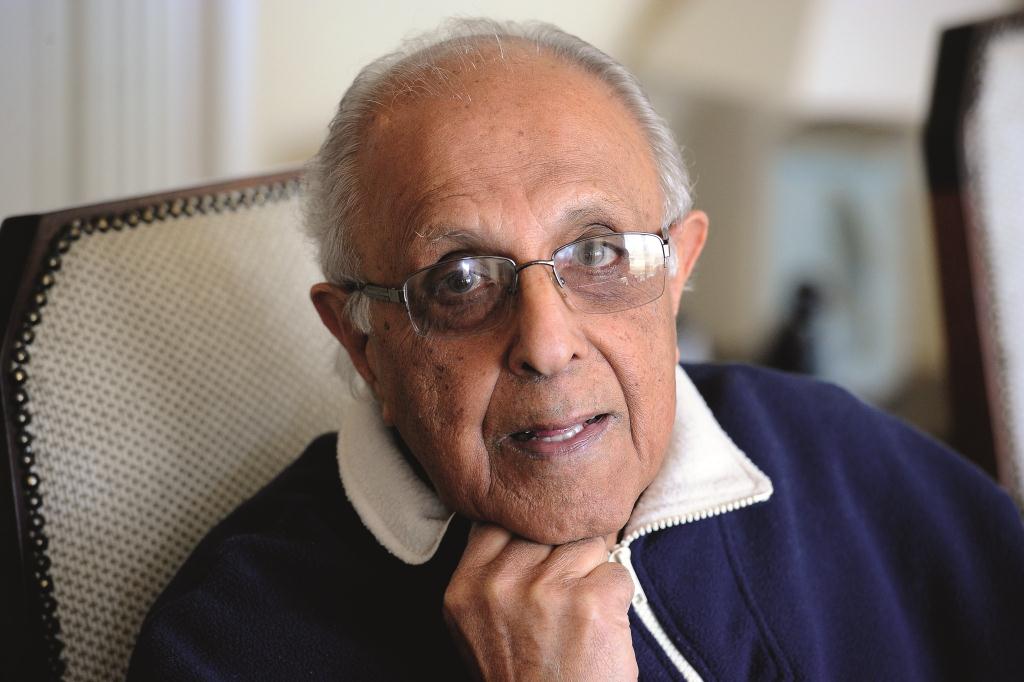

One of the last survivors of the rebels who faced death with Nelson Mandela was a genial soul with a resolve of iron.

Ahmed Kathrada was one of the great worker bees of the struggle against apartheid in the 1950s and early 1960s. In the shadows of Liliesleaf, a smallholding in the middle-class northern Johannesburg suburb of Rivonia, used as a hideout by underground activists, Kathrada, wrote, worked and photocopied pamphlets tirelessly. When the struggle called upon him to pose as a white man – he dyed his hair, put on make-up and a moustache to pretend to be a Portuguese man called Pedro. It was a disguise that fooled people; despite this, he never felt comfortable going into restaurants where people of color were not allowed.

Discomfort in the heat of an armed struggle, against a brutal regime, shows the gentle soul that was Kathrada. He may have been strident when it came to principle, but never fell for bravado; humility was his middle name. He admitted to me once, in an interview for CNBC Africa, that he feared he could have broken if he had been tortured by special branch after his arrest half a century before. His heart was always tender and 26 rough brutal years in prison left few callouses. Once, on national radio, I heard Kathrada break down when a caller reminded him of a comrade who had been tortured to death more than 50 years before.

Kathrada’s widow Barbara Hogan and nephew Nazir

If the scars were deep, Kathrada’s spirit kept a salving sense of humour. With a laugh, he told me how Govan Mbeki – the father of South Africa’s former president Thabo – used to sell eggs he coaxed from the Liliesleaf chickens to his fellow activists, despite their protestations. He also told me how the underground activists of Liliesleaf used to sell vegetables.

Loading...

“Our best customer was the Rivonia Police!” he chuckled. It was the police of Rivonia who raided Liliesleaf with dogs, in July 1963, putting Kathrada behind bars on his way to trial for sabotage that carried the death penalty.

Even in the shadow of death Kathrada, in the so-called Rivonia trial in Pretoria, never lost his sense of humour. Prosecutor Percy Yutar quizzed him, on the stand, about a person who went by the initial K, referred to in Nelson Mandela’s diary. Yutar pressed in an attempt to humiliate: did Kathrada know anyone with the initial K?

“Yes,” replied Kathrada, “Mr Khrushchev.”

Even the judge laughed. The court spared Kathrada and his comrades the rope at the end of the trial in 1964.

“We subsequently found out that life was to mean life,” he said with gentle irony through his trademark smile.

When Kathrada emerged from prison, in 1989, apartheid had taken a lot more than his youth; it also took his birthplace. The place he grew up in, Schweizer-Reneke, in South Africa’s North West province, was bulldozed by the authorities in the cause of keeping the races apart.

Incarceration took even more. Computers, hotel room cards instead of keys and the paraphenalia of the modern world were a mystery. He tried driving on motorways that he had never seen, once, but found it too stressful. Even a harmless ATM spelled confusion as Kathrada found out one Sunday morning when he went to draw money with fellow Robben Island prisoner Laloo Chiba.

“He put in his card and it was swallowed, then I put my card in and pressed a few buttons and it was also swallowed. We had to phone the bank and they came to open up the ATM and get our cards out. Now Barbara gets my money for me,” he told me.

Former minister Barbara Hogan was Kathrada’s loving partner and they appeared kindred spirits. Kathrada would have loved to raise a family – a big gap in his life. The prison guards, on Robben Island, used to keep children cruelly out of sight of prisoners; Kathrada told me of the pain of more than two decades without that most natural sound; the carefree laughter of a child. Hogan was his family.

“When I phone home from overseas my first question is: ‘What happened in Isidingo (A TV soap opera), my second question is about whether the country has been overthrown!” says Kathrada drily.

One or two people in the African National Congress would whisper to you that Kathrada could be a bit star struck when it came to big names and would occasionally drop everything to be with them. It was Kathrada who accompanied the then United States senator Barack Obama to Robben Island.

When it came to integrity, there was never a waver, nor whiff, of scandal around Kathrada. I shall remember him for six words he shot back to me in the studio in 2010. I ventured that there was a rising generation of young people who chose not to know, nor care, about the causes and sacrifices of the struggle.

Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and Julius Malema at the funeral in Johannesburg, South Africa

“That is what we fought for.”

The principled and upstanding way of Ahmed Kathrada that South Africa is poorer for losing; sadly, many of those principles he fought for have been abandoned by a generation old enough to know better.

Loading...