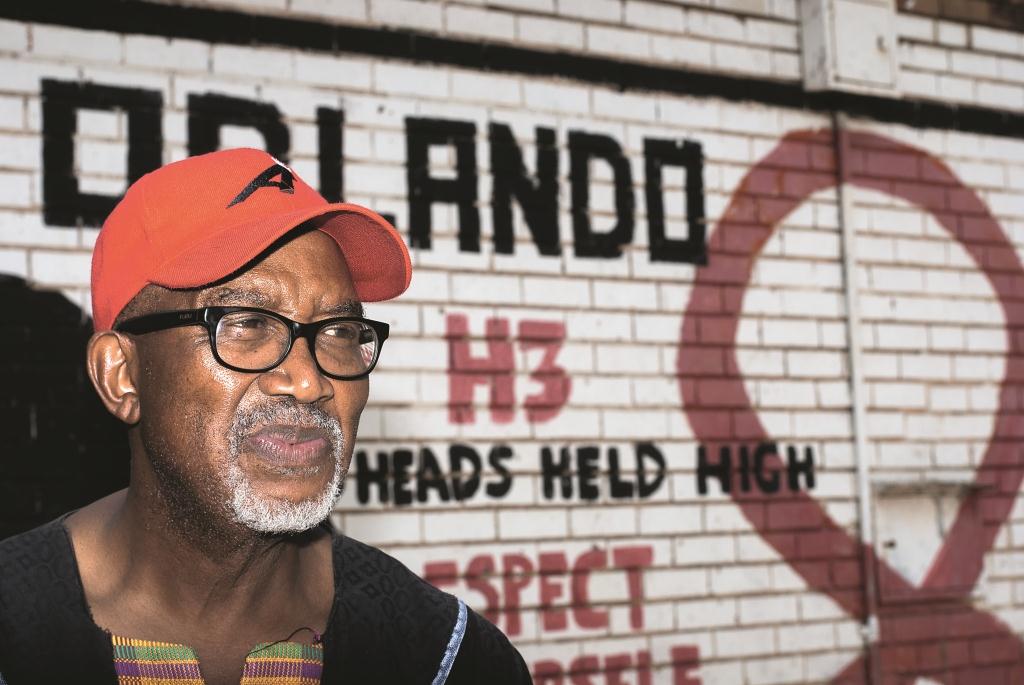

It’s a busy Thursday morning in South Africa’s famous Vilakazi Street, in Orlando West, in Soweto with tourists roaming about. This street was not only home to two Nobel Peace Prize winners, Nelson Mandela and Archbishop Desmond Tutu, but also legendary musician Sipho ‘Hotstix’ Mabuse.

On this day, at a wine bar, Mabuse leans on the table to make his point. He feels up-and-coming musicians should be wary of exploitation.

“If one is not stable then you lose your mind and values. When you’re young, starry-eyed and ignorant you get so exploited by promoters, record companies; everyone takes advantage of your naiveties. If you don’t have resilience you end up an alcoholic or a drug addict just to numb the pain of what the industry can inflict,” he says.

Mabuse started playing the drums at the age of eight, an instrument that he would master so well that a fellow band member, Condry Ziqubu, gave him the nickname ‘Hotstix’.

Loading...

His journey began 50 years ago, when he formed a band, The Beaters, at high school in Soweto.

“We were adored by the media and everyone. The Beaters became popular among the students in universities and high schools. We toured to neighboring countries like Botswana, Lesotho and Namibia.”

In the 1970s, they visited Zimbabwe as an Afro-funk group and named themselves in honor of the future name of the capital city.

“Zimbabwe was known as Rhodesia back then; we were influenced by the grounds of black consciousness. We were conscious of our surroundings and interacting with the struggle itself. It was imperative for us to change the name to Harari.”

In 1982, the band split. A devastating moment for Mabuse. He likened the split to a beautiful marriage that suddenly crumbles.

“I had put so much energy, love and commitment in the band. I felt like all my efforts were in vain.”

Mabuse launched his solo career and produced the hits Jive Soweto, Rise and Set Me Free. His funky township disco-jive jam, Burnout sold 500,000 records.

“A band member passed away while we were in Harare. Before his death, I made a promise to him that because he made fire when the cold wind was blowing I’ll keep the fire burning. One of the things I did was to go to studio and record a song Set Me Free. I don’t know if it was somewhat a paradox that was I refereeing to the split itself or allowing myself to go solo,” he says.

Staying on top is hard.

“To stay relevant, one has to be inventive. My music evolves with my age. I performed at some event recently and I was amazed at the response. When I started playing, the response was just overwhelming. I get goosebumps because I didn’t imagine that people would still remember the music I did 40 years ago. After I performed they kept asking for more,” says Mabuse.

“Music has provided me with things that I never imagined I could have. I managed to build homes, raise my children, and travel the world. If it wasn’t for music I wouldn’t have had the privilege of meeting the late Nelson Mandela or Bill Clinton.”

All of this didn’t come easy. For black musicians under apartheid, performing was a struggle.

“It was difficult to make music freely. I remember we were performing with Percy Sledge, an American artist. Black musicians were curtain-raisers and we couldn’t play in certain white venues so that white people could not see us. If we were found in town after 12AM, we had to state why we were there. If we say we’re a band, they’d ask what is a band? For them, black musicians were nothing but vagrants.”

With fluctuating royalties, Mabuse says it’s difficult to save money.

“The music industry is fickle. We don’t get jobs that continuously pay us. It’s important for us when we get money to plan around it but we cannot have a saving plan. Sometimes musicians stay for two to three years without getting royalties.”

According to the 66-year-old Mabuse, a retirement annuity is a must.

“People don’t understand how important it is. If I knew what I know now about money 40 years ago, I probably would have been a billionaire.”

Mabuse and his band members dropped out of school in Grade 11, for music. He says fame made them lose focus.

“In high school we dropped out without realizing it. The pressure was too much, so was the music, the money and women,” he says.

In 2012, at the age of 60, Mabuse joined an adult basic education training program at a school in Klipspruit, Soweto, to get his matric.

“Now that I’m older and wiser I know that education is powerful. I am grateful that I was able to get education, otherwise I would not be getting royalties because I wouldn’t have the knowledge of what music means in terms of financial and economic gains. I still get royalties for all the music I released,” he says.

He recently produced a documentary about his song Jive Soweto for the BBC. He also plans to study anthropology at a university away from home.

For musicians, maybe it’s better to remember his parting words rather than his songs.

“If they do not have expertise, it’s better to invest with those that have expertise. First of all, find a good lawyer, manager and pay them. If you don’t have money, get them into some kind of a deal because then you will be protecting yourself for a lifetime. Stay focused and don’t believe the hype.”

Maybe young musicians should print out these words and put them on the wall.

Loading...