He dreams big yet it all started in a small corner. It was in a corner of the dusty streets of Mafikeng in the North West province of South Africa where he first drew a crowd, in school theater, at the age of six.

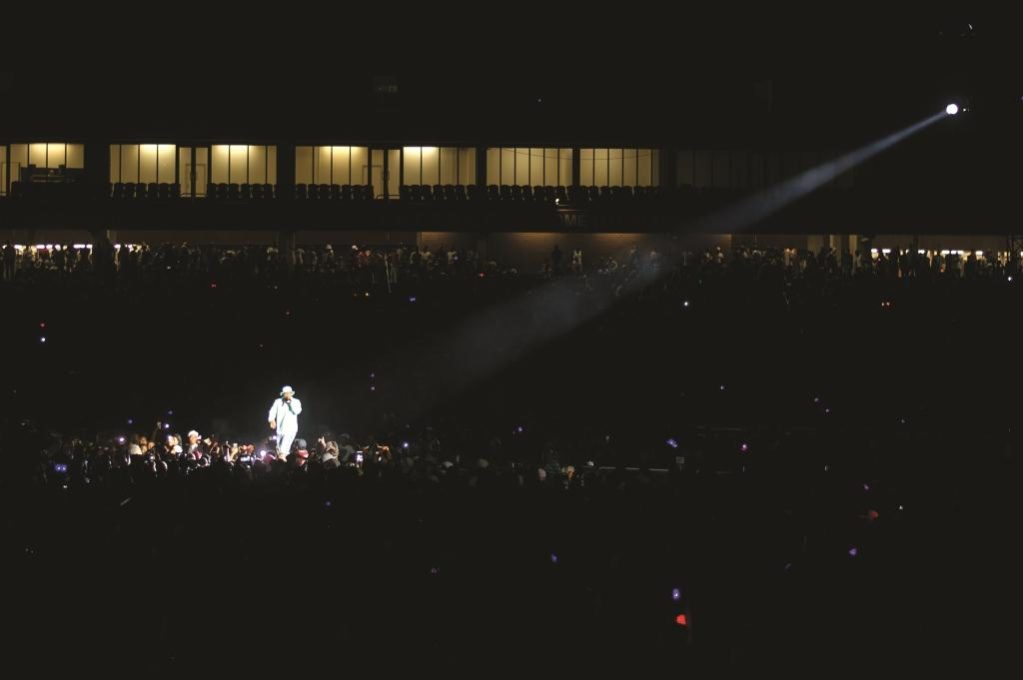

He’s broken barriers, filled the 20,000-capacity Dome, in 2015, and this year, he’s pushed it further by attracting around 36,000 fans to Orlando Stadium in Soweto – most football teams fail to do this. He’s proved that nothing you put your mind to do is impossible.

This is Refiloe Maele Phoolo, known as Cassper Nyovest to the world. Rapping is his game.

He steps out of a minibus with his entourage, they stop for a selfie, and I’ve noticed how spruce his style is: a bandana, a R500,000 ($37,000) watch, gold neck chain and all-white outfit. A closer look at Cassper reveals puffy eyes; he is exhausted from back-to-back performances.

Loading...

Cassper is best known for his hit song, Doc Shebeleza, and his ponytail that he cut off not long ago.

“It kind of made me look like a gimmick; there are certain things that hold you back. When you are animated it makes it too difficult to grow up. It was time to take it off because I am more mature now,” he says.

“I wouldn’t want to be this version of myself forever, I want to get better.”

All of this didn’t come easy.

The 26-year-old was born into a family of teachers, where education was important, yet he doesn’t have a qualification beyond school. He dropped out of school in grade 10, at the age of 16. His parents didn’t approve.

“It was a very emotional part of my life, and theirs as well because they are passionate about education. I sat them down and said look I’m not saying I wanna quit school and sit at the corners and smoke weed and drink my life away. I want to work, on my dream and my purpose,” he says.

Luckily they understood.

“I understand that school is very important, I wouldn’t say that school wasn’t for me but it’s just that my path was a little bit different from the normal life and what my parents thought I would do.”

He had a plan up his sleeve and went to the big city of Johannesburg for music.

“I was signed to a label called Impact Sound under Thabiso Tsotetsi; he didn’t wanna be associated with a child who dropped out of school so he watched from a distance. That’s when HHP, a fellow artist, saw me and we did a song Wamo Tseba Mtho,” says Cassper.

After two years of struggle in Johannesburg, he moved back home.

“My grandmother gave me a mattress because I didn’t have anywhere to sleep and it took a very long time for anything to happen.”

“Nobody cares who you are, people function by the monopoly of those who know each other, pull each other up, it’s not even about talents, it’s about connections and who you know,” says Cassper.

He used his sister’s last R100 ($7.50), meant for a transport fare, to buy himself a return ticket to Johannesburg.

Things started to turn around. Cassper started his career with Childhood Gangsters, a group he started with his friends. When it disbanded, he went to launch his solo career and produced the hits Gusheshe, Malome and Mama I Made It. He also shared stages with international artists Kid Cudi, Kendrick Lamar, Nas, Wizkid and Wiz Khalifa.

The rapper also started his own record label, Family Tree, the same year he released his debut album, Tsholofelo – a taste of sweet success followed by a string of awards.

“Artists get only eight percent of their record sales, [it’s the] industry standard, and 50 percent of their show money. I didn’t want that, I wanted 100 percent of everything,” he says.

His favorite line: “God is good all the time and all the time God is good.”

It hasn’t always been good for Cassper who was involved in a public fight with fellow South African artist Kiernan Jordan Forbes, known as AKA, which led to both artists recording diss tracks about each other. Much to the public’s surprise, after Cassper’s show at Orlando Stadium, a picture went viral on social media of the two artists congratulating each other.

“Kiernan and I have been cool for a while now. We didn’t even know what we were fighting for and it didn’t make sense anymore. We were just talking how the fight was pathetic and it was over and we had to move on. We couldn’t believe how far we had made it in our careers. Every time we see each other we greet, so that picture for me wasn’t like the moment everybody made it out to be.”

“Kids really look up to us and they would do anything and everything that we do. If I’m always in the paper for doing some dumb stuff, what am I teaching them?” he says.

A few months ago, Cassper was accused by his idol, Kanye West, of stealing his floating stage idea. The rapper denies this.

“I did that stage last year at the Dome before Kanye did his show. How could I possibly have stolen his idea? I just think that it’s great that my idol knows my name and we’ll have something to talk about the day we meet. For me, it was a compliment no matter how it came out.”

Cassper has been through a lot of bad publicity in his career; he says negativity is a thing of the past.

“I can’t deal with fights. I just become a person I’m not,” he says.

Cassper says getting to the top is the easy part; staying there is harder.

“The hardest part is maintaining the same spot. In South Africa, people move on very quickly and they forget and what you have done in your career doesn’t matter in South Africa.”

His worst fear is to be forgotten.

“I don’t ever want to get to a place where nobody knows who I am, where I’m not celebrated and people don’t love me as much as they do right now, I don’t ever wanna get to that place.”

Even though Cassper fell short of filling up the 40,000-seat stadium by just a few thousand it did not dampen his sense of accomplishment and musical bravery. In 2017, he’s looking to fill up the 94,000-seat FNB stadium.

“At the Dome I lost R3 million ($220,000) but the concept was not to make money but to shift culture. The value was not in money but an investment… I want to get to a point where an artist can walk away with R8 million ($600,000) a show.”

“South African hip-hop is the biggest music. We are African hip-hop,” says Cassper.

Love him or hate him, what is clear is that Cassper has shaken up the music industry.

“Maybe I should start acting broke now coz my success turned the game into a cold heart”. These are the lyrics from his popular hit Malome.

“Me and my dad never have one-on-ones anymore” are lyrics directed at his father who separated with his mother, at the same time when his 19-year-old brother died in an accident.

“When my brother passed away, it was a sad time for my family and it was also the first time someone from my immediate family died. Then my parents separated so, at the age of 15, I had to grow up and be a man of the house,” says Cassper.

According to Cassper, South African artists are far from famous.

“The only guy who’s actually gaining traction is Black Coffee; he has a following that’s growing all over the world. But when I travel the world I perform for mostly South Africans. I just had my first show in Germany, for Germans, who liked my music. Before that we’d create our own shows.”

“As much as we’re making it look like we’re flourishing out there, in the US, we are very far. But we’re fighting and I think our time will come.”

He is too humble to offer any estimation of how much he has banked this year.

“When I started to make money I mentioned it too much to my fans and then I became the guy with a lot of money. I’ve learned that it creates a wall between me and my crowd because they don’t see me as one of their own anymore. It’s a big mistake that I made at a very early stage in my career,” he says.

“I’ve also lost too much but it happens to a lot of us who don’t know what to do with money. I posted everything I did and everything I bought.”

According to reports, the rapper makes R120,000 ($9,000) a show, excluding accommodation, flight and his entourage.

One of his challenges is getting his music played on radio; he asked his 685,000 followers on Twitter to help him get his new song Abashwe played.

“Please help me push it. I still don’t understand why I don’t get radio airplay so I need my fans to request Abashwe. Hope that will help.”

He’s got this far without radio; imagine where he’ll get to if his songs are on the airwaves.

Loading...