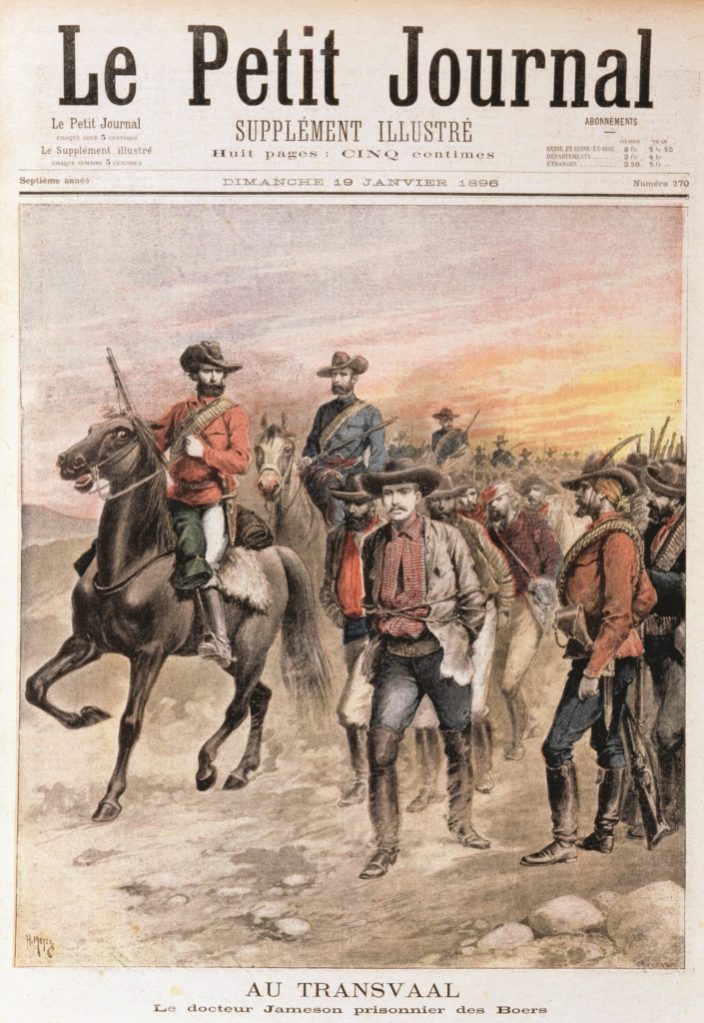

They were led by cavalier gentlemen who believed they could overthrow an African government with 600 men, eight Maxim machine guns and three light artillery pieces. It was a band of brigands, aristocrats, adventurers and opportunists who carried out the so-called Jameson Raid on Johannesburg in December 1895 – one of the greatest botched coups in African history. On July 28, it will be 120 years since their trial ended in London in 1896 where the raiders got a slap on the wrist for trying to jump a country – their leader, Leander Starr Jameson, was one of many who walked free from prison five months later.

FORBES AFRICA looks at what would have been made of the Jameson Raid in the 21st century. For a start, it would have been the cellphone and not the gun as the lethal weapon, according to strategists.

“In some aspects war has never changed. For a start, it’s getting the right amount of men into the right position. Today your first prize would have to be an attack on a digital level,” says Colin Webster, Secretary General of Mind Sports South Africa (MSSA).

By day, Webster is a tax consultant living in Germiston, in the east of Johannesburg. On weekends, he is a three-time World Champion of Ancients Warfare of the International Wargames Federation.

Leander Starr Jameson, Scottish-born South African politician,

Loading...

“What you would want to do is, like in the Jameson Raid, rely on the chaotic state of affairs between different nationalities. To attack a country you need to create the chaos. For example, in World War Two, the Germans created huge printing presses to create counterfeit currency. The idea was to devalue the British pound.”

“With technology it’s become so much more complicated. You would have to disable the entire country’s electronic infrastructure. A country sitting without its internet, TV and radio, makes it difficult to get information out to different regiments. It’s not impossible because all you need is a couple of electromagnetic pulses (a bomb that will fry your electronics) in the right places.”

Webster’s great grandfather was a commandant at Pilgrim’s Rest, in Limpopo after the South African War.

“I prefer the historical gaming, to computer games like Age of Empires, because it is all interactive with people. There are three different types of wargames that you will play. One is competitive. Two is recreating a battle from history. The third is simulating a battle.”

“Warfare today has become a very different kettle of fish. A lot of it is computerized. Your whole way of conducting a battle is different from the less technological society during the Jameson Raid. You have to realize the ranges of weaponry today far outrange anything that’s previously handled. These days you are able to pinpoint where you are going to fire your shells.”

Another strategist is John Smith, not his real name, an investment analyst living in Johannesburg and a World War Two re-enactor hobbyist since 2012.

“Your main goal is to consolidate your power as quickly as possible. You want to seize the initiative – always attack, always strike first, always keep your opponent reacting instead of planning – and you want to cover as much ground as quickly as possible.”

Winning over the masses, controlling utilities such as water and electricity, and controlling the media are all part and parcel of success, says Smith.

“In the modern world, your most important technology is the media. Mobile phones, social media sites – you must control them. War in the 21st century is not about who has the smartest tank or the lightest assault rifle – Iraqi IEDs and Afghan tank traps and Syrian barrel bombs have proven that. Your most important tech is that which allows you to control the media – and to sell your ideology. Take internet servers offline, hack into television broadcasters, breach government websites or take them offline through DDOS attacks – that is the tech that will count. Whether your protestors are armed with AK47s or the latest German assault rifles means little when you are losing the media war.”

There was little media back in 1895 when doctor and magistrate-turned-soldier adventurer, Jameson, set off from the small town of Pitsane, just across the now Botswana border on December 29, 1895. The idea was to overthrow the gold-rich Transvaal run by Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic (SAR). Jameson banked on the raid triggering an uprising of so-called Uitlanders, foreigners, working in the mines in Johannesburg.

The mainly British Uitlanders outnumbered the Afrikaners two to one, paid taxes and had no vote. The plan was for them to seize the armory in Pretoria as Jameson rode in to Johannesburg.

It all fell apart when Transvaal troops stopped the raid dead in its tracks in Doornkop, 26 kilometers west of Johannesburg. The Transvaal soldiers had tracked the raiders from the minute they crossed the border. Jameson’s men believed, mistakenly, they were safe because they had cut telegraph wires to Pretoria; all they had cut was a fence.

Jameson suffered the ignominy of borrowing a white apron from an old woman as a makeshift flag of truce. The prisoners were sent to Pretoria and then to London for trial, after diplomatic horse trading.

“The Jameson Raid could have worked if it had successfully divided society. The Jameson Raiders were backing on the Uitlanders to support them against the Transvaal government. They were relying on Uitlanders, who were mainly British, however the [Uitlanders] had no intention of supporting the Jameson Raiders as they were quite happy with the SAR,” says Webster.

These days, an attack on a government would be a different story.

“Any battle relies on surprise. It would be extremely difficult today to do a raid on South Africa because of South Africa’s infrastructure… South Africa has one of the best armies in Africa, you would have to have the backing of a foreign government. That’s not going to happen today. From that point of view South Africa is very safe and secure,” says Webster.

“There are a number of international arms dealing laws and treaties in place, making it difficult for the nefarious plotter to get his hands on weaponry in general. This leaves the darker avenues. Seize existing stockpiles of weaponry from the current government, like the Arab Spring in Libya or Syria, or on the black market. This is usually an expensive and low-quantity proposition, and is better suited for getting niche items like a shoulder-launched anti-air missile for shooting down a civilian airliner than arming large numbers of insurrectionists at a time,” says Smith.

The full force in Jameson’s repercussions were felt in South Africa. Its backer, Cecil John Rhodes, mining magnate and Prime Minister of the Cape Colony, was forced to step down. His British South Africa Company paid £1 million in compensation. Other conspirators were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to death; this was commuted to 15 years.

As for Jameson himself, he was sentenced to 15 months and released after five. Eight years later, in 1904, Jameson went on to become the Prime Minister of the Cape Colony. Not a bad outcome for a gentleman convicted of treason who botched a raid to remove an African government. Jameson was buried on a high rock outcrop in the Matobo Hills, near Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, a few hundred meters from the right hand of Rhodes. What stories they could tell.

Loading...