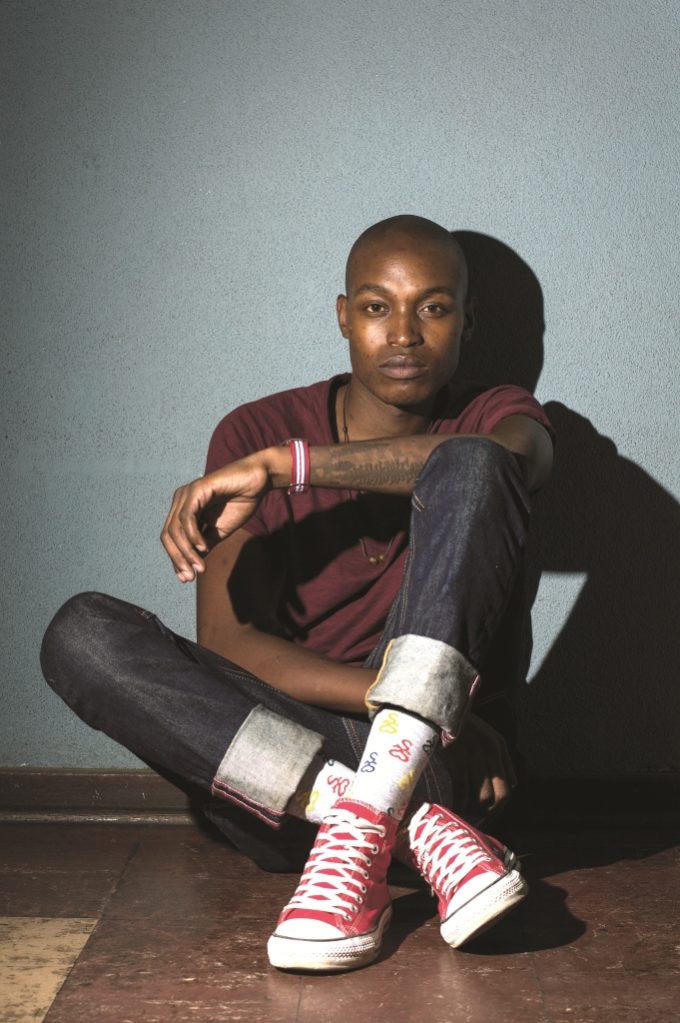

Tshepo Mohlala remembers being forced to wear a green blazer at church because his grandmother said so. He says she had style; she was also the pastor and still is. Clothes were always a big part of his life, now they’re his fortune.

Mohlala grew up in a small house in Tsakane, 50 kilometers east of Johannesburg, living with mostly women at their grandparent’s house. This was because of his parent’s sudden divorce and many hard years. It was here that his love for fashion unfolded.

He moved from home to home because his mother kept changing jobs as a domestic worker. At the one house they lived in a backroom behind the home.

“We stayed there for two years and it was terrible, we weren’t allowed to do certain things,” Mohlala says.

“We had to move back to Tsakane, our granny’s house. The great thing is that we moved back with family.”

Loading...

Mohlala and his family didn’t have it easy. When they couldn’t afford clothes, church members would bring them some.

“It felt good and often I was often first to choose,” laughs Mohlala.

Soon after, Mohlala went to Brakpan High School where he completed his matric, things were easier than before. His mother got a better job in Centurion, around 20 kilometers south of Pretoria.

“I was forced to join the church choir!”

“Choir was exciting. I looked forward to it because my friends and I would talk about our dreams. We were all from the same background; small houses, grannies, church and having no fathers,” says Mohlala.

Clothes were never far away. At choir, Mohlala met the creator of Skinny Sbu Socks, Sibusiso Ngwenya, and social media strategist, Mpumelelo Jules Kumalo.

They were all passionate about fashion. They sold second hand suits at church to make extra money. They bought them for R250 (around $16) and sold for a lot more.

Their dream was to arrive in Johannesburg, 28 kilometers away, and become entrepreneurs, meet celebrities, and make a lot of money, he says.

In 2010, Mohlala went to Johannesburg to study cinematography, but clothes and fashion were always on his mind.

“I remember walking with my girlfriend from choir to buy food and we were wearing skinny jeans. The guys gambling on the street corner laughed at me saying I’m gay. I was fashion forward,” he says.

Inspiration came from strange places. Thugs would come to Mohlala’s grandmother to confess their sins; young Mohlala was impressed by the criminals’ dress sense. His grandmother, the pastor, approved their elegance, if not their deeds, and advised Mohlala to look as stylish.

“Not only criminals came, even the good guys. My gran just wanted me to be a gent and look good,” he says.

But Johannesburg was not paved with gold as they had thought. It was grimy and hard work.

Mohlala mingled at fashion events. He met a lady at South Africa Fashion Week and told her he wanted to be a stylist. He was told to study fashion. And he did in 2011.

Mohlala had to drop out a year later because he couldn’t afford tuition fees. He told himself he was not going back to the streets of Tsakane. He moved to a one-bedroom flat in Brixton, Johannesburg, with his friend from church, Ngwenya. He made money through promotions, also getting rejected by retail stores. He recalls this as his worst and hungriest year.

Then came another fashion week where he met Felipe Mazibuko, the South African stylist and fashion guru. Mazibuko liked his style and they exchanged numbers.

They met over lunch the next week and Mohlala was introduced to fashion veteran Olebogeng Ledimo, the founder of House of Ole, who had an event coming up.

“We drove around that day with Ole’s Jeep in Braamfontein and I couldn’t believe I was meeting so many people I see on television,” he says, still in disbelief.

He worked with Ledimo and Mazibuko on a campaign for three weeks, he also made friends and potential business partners. Mohlala never looked back.

Months later, AfrikanSwiss was created with two former co-workers from the 2012 South Africa Fashion Week. Their idea was to create the first premium genuine-denim in South Africa. The trio gave the jean industry in Johannesburg a facelift. Their focus was menswear.

The brand was growing immensely and they were showcasing at international events in 2013, dressing international R&B group 112 and producer P. Diddy on their tour. They were also involved in photoshoots with the Dutch shoe brand, Palladium.

“We were going to be part of all that vibe,” he says.

In 2014, AfrikanSwiss opened a shop in the heart of Johannesburg and continued budding. As things were blossoming, it turned sour, says Mohlala.

“Emotions and business clashed, the vision of the business clashed too. We were not on the same page anymore.”

Mohlala stepped down and decided to go solo. He continued making jeans and promised not to compete with AfrikanSwiss.

Mohlala took this time to do market research and study the denim industry by searching for loopholes to take advantage of. He found an opportunity, took the little money he had saved and used it to produce his first range of jeans. He named his jeans, Tshepo The Jean Maker.

The jeans are cut to fit the target market’s lifestyle, which can be worn formally or casually. The design details are seen inside and out.

“Our fabric is sourced locally. My jeans are raw unwashed and are made to take the shape of the wearer,” he says.

Most of Mohlala’s sales are made through social media and he has sold as far as Atlanta in the United States.

The jean maker is fast growing and slowly transforming the denim industry. He was a choirboy inspired by thug attire; he’s now a young man exporting jeans to the world.

Loading...