Next year marks the fifth anniversary of Ronald Harrison’s death. He was 71 when he succumbed to a heart attack, alone in the house of his niece, Desiree Phillips, in Mitchells Plain. His quiet death was a far cry from the noise his controversial painting caused almost 50 years before.

“We came home that evening and we found him lying on his bed,” says Phillips, who remembers June 28, 2011 like it was yesterday. “I thought he was sleeping, but when I went into the room, I realized that he had passed on. It was a great shock. We knew he was not always well. He had become weaker. The year before, my uncle had undergone cancer treatment, of which he recovered.”

While Harrison’s death left her family bereft, Phillips says that she is, to some extent, happy that her uncle died the way he did.

“He was not the type of person who wanted much attention, or to put anyone of us through any stress – for instance by running around and taking him to hospital,” she says. “I am sure that he died the way he wanted.”

When looking back, Harrison’s death seems to have gone largely unnoticed. Apart from various media outlets carrying the story and some civil society organizations expressing their sadness, there was not much commotion. Phillips is not bothered by this.

Loading...

“My uncle was a proud man but very humble. He didn’t have the urge to be recognized or rewarded for what he did,” she says, referring to The Black Christ.

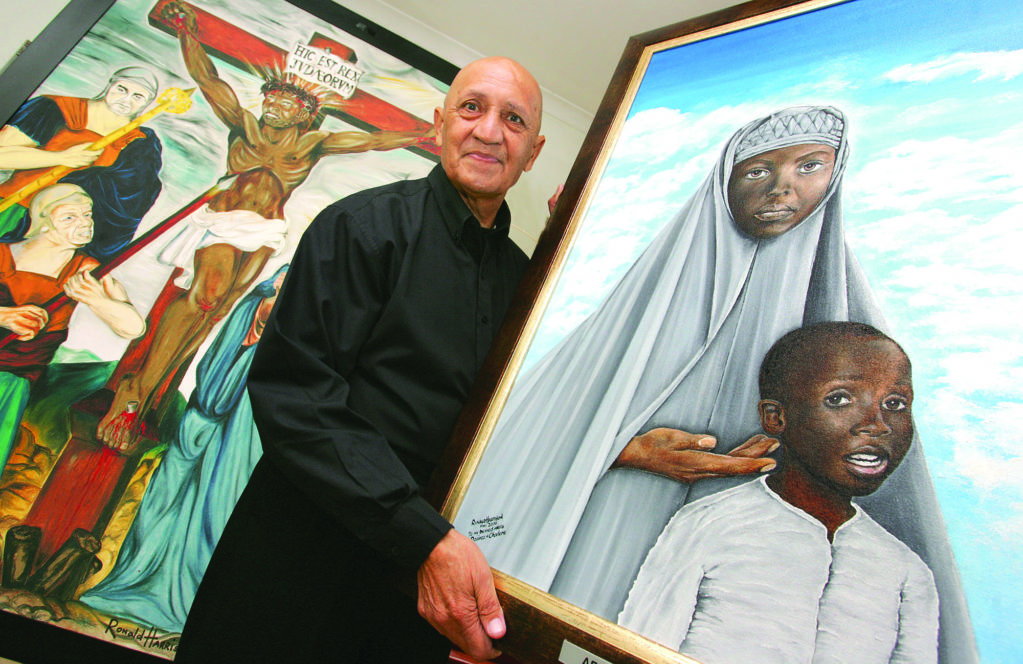

The oil painting, which has been described as one of the most profound and controversial paintings in South African history, depicts apartheid struggle hero, Albert Luthuli, as Jesus Christ and apartheid architect, Hendrik Verwoerd, and former justice minister, John Vorster, as Roman centurions.

“Ronnie was a great admirer of Chief Luthuli, who was banned after winning the Nobel Peace Prize in 1960,” says the artist’s brother Desmond. “In his eyes, Verwoerd and Vorster had crucified Luthuli for his beliefs. That is where the idea for this piece came from.”

Desmond adds that while the family knew the artist was painting something interesting, they didn’t know what.

“In the beginning we didn’t know what Ronnie was up to. We were astounded when we saw the end result. My mother told him that he was going to be in a lot of trouble.”

A lot of trouble, indeed. Shortly after Harrison finished his painting, it was displayed at St Luke’s Anglican Church in Salt River, Cape Town. It didn’t take long before the security police got wind of it. The painting was then smuggled out of South Africa by anti-apartheid activists, after which it toured Europe for a while. In the process it raised significant sums of money for the International Defence and Aid Fund. Established in 1956 by John Collins, a priest from London, the fund covered the legal expenses of those accused of treason by the apartheid regime.

When the authorities realized the painting had left the country, they arrested the then 22-year-old Harrison. Days of interrogation and torture followed.

“I suffered the most severe humiliation and interrogation over a period of seven days,” Harrison told the BBC in 2004. “Everything that they say about those horrendous Nazi-style tactics is true. It’s just too humiliating to talk about.”

“My brother went through hell. He suffered a lot. Ronnie was mentally very strong, but never really recovered. Physically, he was never the same person again,” says Desmond.

Desmond believes his brother knew exactly what he was getting himself into when he started painting The Black Christ.

“It was his way of expressing his support for the oppressed, and raising his voice against the government at the time. Ronnie was a very peaceful person, and not up for violence. This was his way to contribute to the struggle.”

In his book, which carries the same name as his famous painting, Harrison explained that it was his fascination for Luthuli that drove him into the arms of the fight for freedom.

“I became obsessed with the idea of taking some constructive action in the liberation movement through the medium of my artistic talent. How could a government that professes to be Christian perpetrate such immoral deeds and inflict so much pain and suffering on its own countrymen simply because its supporters were of another race, another color, and another creed?”

As the painting toured Europe, Harrison and his family lost track of it.

“In Cape Town, we had no idea where the painting was and where it is was traveling. They didn’t want the security police to get hold of it,” says Desmond.

In the seventies, The Black Christ ended up in a basement in London.

“It survived a great deal, including flooding, which flooded many basements but not the one where the painting was kept. Eventually, Ronnie and The Black Christ were reunited in 1997. He managed to track it down via The Observer and then took it home with him,” says Desmond.

It was displayed at St Luke’s for a while, after which it was moved to the South African National Gallery in Cape Town.

While Harrison will always be remembered for The Black Christ, his name adorns many more paintings. Most of his pieces he painted as a teenager and adult were influenced by politics.

“He was inspired by icons who left their mark, like Mother Teresa, Thabo Mbeki’s mom, MaMbeki, Hector Pieterson, who was shot during the Soweto Uprising, and Nkosi [Johnson], the little boy who died of Aids,” says Phillips, adding that she doesn’t remember much of the The Black Christ controversy. “I was one year old at the time when he painted it, but I do remember how passionate he was about his art.”

“He started painting from a very young age. He must have been eight or nine years old, I think,” says Desmond. “He used to get my mom and dad to pose for him as his models. He really had a natural talent.”

Harrison fed his passion for the arts until the day he died.

“Before he passed on, he was busy with a series of six paintings. He finished the fifth one two days before he died. The sixth one, he never touched. We still have those pieces,” says Phillips.

Harrison’s family remember him for the role he played at home.

“He lived with us since my mom and dad got married, him and his mom,” she says. “He was a real father figure. I remember him as a very caring person, someone who always put other people’s needs ahead of his own. He never married, and looked after his mother until she died at the age of 90. That was the type of person he truly was,” says Phillips.

Harrison rests in peace at St Luke’s in Salt River, the same place the The Black Christ caused so much turmoil.

Loading...