This calm encounter on a spring morning in Sandton, Johannesburg, belies a man who forged his career amid fury. He cheated death at the hands of police to capture the Soweto school uprising, surely, one of the saddest stories ever told in Africa.

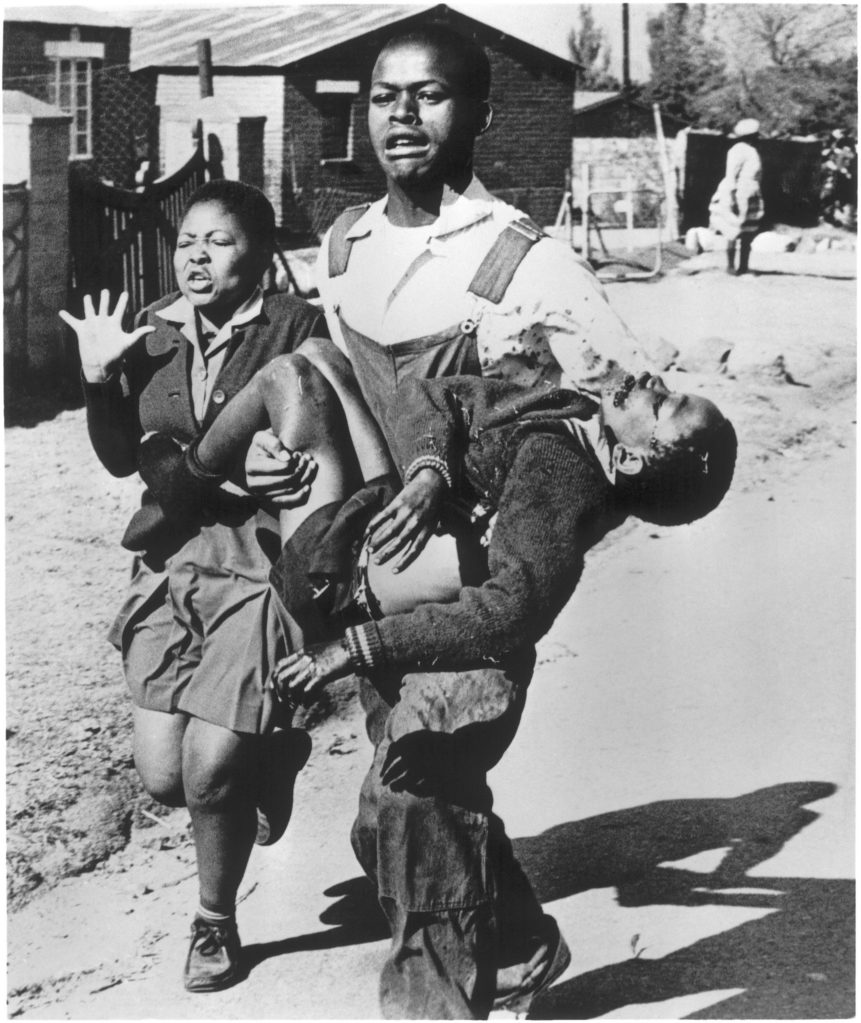

On June 16, 1976, Sam Nzima, a photojournalist at The World newspaper, in Johannesburg, took a picture of Mbuyisa Makhubo carrying a 13-year-old dying Hector Pieterson from the Soweto massacre. He smuggled the film out in his sock and the picture hit the front pages of the world. The police wanted to destroy it – the image destroyed Nzima’s career.

The picture changed the political landscape of South Africa; it made a fortune for the news agencies of the world, but he got nothing from it for 22 years. The iconic image has been on everything from billboards to T-shirts.

“The picture of Hector Pieterson destroyed my future in journalism. I couldn’t continue as a journalist because of that picture and I would never put my life in danger, I was forced to leave everything behind,” says Nzima.

Loading...

Harassment from police forced Nzima to become a small bottle store owner in the small village Lilydale, in Bushbuckridge, in Mpumalanga. It took him 22 years of struggle to get his copyright back.

“The copyright of the Hector Pieterson Photo was given to me on the November 16, 1998 by Independent Newspapers Holdings Limited and was registered with Webber Wentzel Bowens Attorneys Notaries & Conveyancers intellectual property lawyers in Johannesburg on July 20, 2000,” he says.

The day he risked his life for the picture is as clear as yesterday.

“As early as 6AM in the morning of June 16, I was covering a student march in Naledi High in Soweto with a colleague Sophie Tema. We found the students busy writing placards opposing new Bantu education laws. This followed a circular sent to the schools that Afrikaans will be the medium of instruction,” says Nzima.

When the march reached Morris Isaacson High, a student leader Tsietsi Mashinini addressed students from the top of a tree saying the march was to be a peaceful, says Nzima. Shortly after, armed police arrived in armoured vehicles and instructed all to disperse. The children sang Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika in defiance.

Nzima says the singing agitated a police commander who instructed his officers to open fire. The students ran and Nzima hid in a house.

“I got out from the house, the police had ceased firing, and I saw a little child falling down. There comes this tall boy Mbuyisa and picked him up. As Mbuyisa picked him up, I went with my camera. I was also shooting with my camera, under the shower of police bullets. Mbuyisa was running to the nearest car, the nearest press car was our Volkswagen Beetle. I managed to shoot six sequences of him carrying Hector. My colleague Sophie Tema opened the door and they put Hector inside. Hector was certified dead upon arriving in Phefeni Clinic,” says Nzima.

“I knew the police would come back for me, I wound the film and stashed it in my sock and then loaded another film. As I anticipated, the police came back and grabbed me after they ran away for some few minutes. They took my three cameras and exposed my films. When they thought they had destroyed the evidence, our driver Thomas Khoza rushed the film to The World office. The picture was published the next day.”

Nzima’s gallant work with his camera on that violent winter day in 1976 was to wreck his life. When police came knocking on his door, Nzima left his job in Johannesburg and ended up under house arrest in the remote town of Bushbuckridge, far from his family in Soweto.

“After two days I received a call from the station commander at John Vorster Square, he wanted to have a cup of coffee with me. Percy Qoboza was my editor at The World. He advised me to stay away from the police if I don’t want to come back as corpse.”

Qoboza told the commander to invite him, the editor, for tea instead. This led to a police instruction to shoot Nzima if they found him photographing, a police insider told him at the time.

In April 2011, South Africa’s President Jacob Zuma awarded Nzima with the Order of Ikhamanga for excellence in liberal art.

“If popularity was cash, I was going to tell you I am a millionaire or billionaire. Many people know this picture but some don’t know the man behind it. I was shocked in 2010 when I was invited in Berlin at a school called Hector Pieterson Schule. The school was renamed in celebration of the fall of The Berlin Wall. Germans compared their freedom to the South African independence.”

“Money was not that much, no rewards in cash but I had recognition from the state president. At the beginning I regretted [taking] this picture because this picture destroyed my journalistic career, I lost my job and my friends in Johannesburg. But now I am rejoicing because I am getting high publicity, I have become an icon in South Africa. Maybe one day I will reap a jackpot from some quarters.”

A Sam Nzima Foundation will be opened, including a school for photojournalists, in his hometown near Bushbuckridge. This is where Nzima has a makeshift darkroom that he uses to train school children in his village of Lilydale.

“After the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990, I was brave enough to pick up my camera and continue where I left, but all these years I was afraid to do that. The original camera that captured Hector Pieterson is still intact; I have kept it safe in those years.”

When Hillary Clinton visited South Africa for the first time, in the 1990s, she wanted to see Nzima at the Hector Pieterson Museum in Soweto. She offered to buy the camera, but Winnie Mandela advised Nzima against selling. She said it was the property of the state. Nzima also refused to donate his Pantex camera, with 50mm lens, to the ANC Women’s League.

“I was happy not to sell it, but if it was good money she was offering, I would have been happier to sell. It’s because it’s better enjoying my life when I can than keeping the camera. One day, I will show people of South Africa that this is a camera that brought their freedom. But the person who struggled for freedom gets nothing.”

“South Africans do not value me but I do get recognition from other countries. I remember in 2011 I was invited to exhibit my work in Belgium and address the parliament in Brussels. Parliamentarians showed interest in our history and the role I played in those days.”

Despite Nzima receiving lucrative offers from overseas for the camera, he says his conscience disapproves. It lives in his museum in Bushbuckridge.

“Now I cannot sell the camera, it has become the property of the state, it is our heritage. I have to consult with the politicians for a go-ahead; otherwise I will be frustrated again. If the government officials could learn that I had sold the camera overseas, they will ask me why I did it.”

Hector Pieterson was buried at Avalon Cemetery, in Soweto, and a museum in his memory was built near where he was shot, in 2002. His sister, Antoinette Sithole, the girl running alongside, is a curator at the museum and Makhubo was last traced in Nigeria. He went to exile after the photograph was published.

Every year on June 16, Nzima kneels and prays for the fallen schoolchildren of Soweto. He escaped with his life from the terrible day but his career didn’t.

Loading...