It’s hard to believe that two years have passed since the tragic killing of 34 miners in Marikana. The horrific visuals of the shooting on August 16, 2012, remain fresh in the mind. Thousands of mine workers had been protesting against their meagre wages and poor living conditions when police opened fire, killing 34 of them. Police say they were provoked. South African’s were in shock like the rest of the world. Many believe the disaster was waiting to happen while others say the tragic events started a revolution. What did become clear that day is that despite the courageous fight against apartheid being won, the battle against inequality in South Africa is far from over. But has anything changed in the last two years?

Amsterdam, 30-11-2005

International Documentary Filmfestival Amsterdam

IDFA 2005

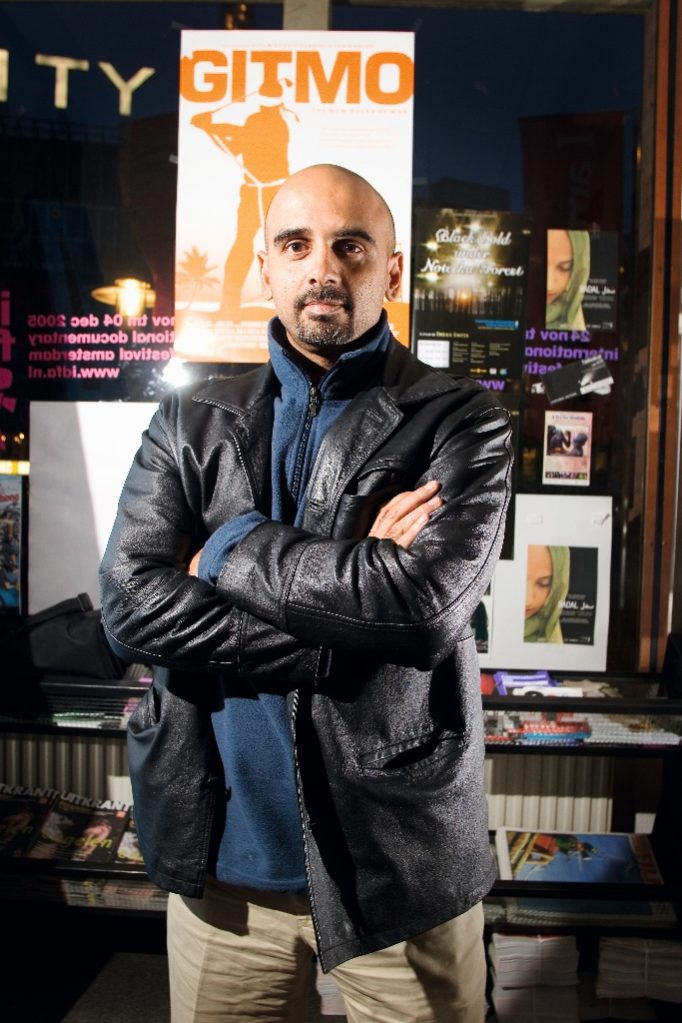

Rehad DESAI

Jury Amnesty Award

Foto Felix Kalkman

South Africa has some of the most valuable minerals in the world. For decades, men have slogged, under poor safety conditions, to recover these precious assets from deep beneath the ground, touching and feeling the gems, but never having ownership of them. The mining industry remains South Africa’s biggest revenue earner. Considering the importance, one would assume employees in this sector would be well taken care of, if not by their employers, at least by the government.

For years, mine workers and labor unions have raised their concerns, hoping for change. The recent Association of Mineworkers and Construction Union (Amcu) strike in the platinum sector made sure that this time the pleas of workers will be heard. Relentlessly, for five months, workers were gripped with poverty, hunger and cold until finally there was some respite. The unprecedented 22-week strike made history. The three major platinum producers finally agreed to higher wages, not what Amcu was demanding but enough to get them to return to the mines.

Reaction to the wage deal was mixed with many industry analysts calling it a loss for the workers. Amcu called it a victory. But will this victory see real transformation in the mining industry?

Loading...

Amcu leader Joseph Mathunjwa, now a household name, says the strike was not just for social justice but also to honor the workers that were killed at Marikana. Two years later, the Farlam Commission of Inquiry set up to probe the shooting is still trying to find out what led to the tragedy and who was responsible.

Political activist and filmmaker, Rehad Desai, has placed together his account of what happened on that day. In his new documentary Miners Shot Down, Desai pieces together witness accounts, interviews with political heavyweights and even victims that survived the shooting, to expose the social injustices that exist on the mining grounds of Rustenburg, 120 kilometers northwest of Johannesburg.

The film also tells a story of how the ANC, a party once obsessed with fighting for human rights and social and economic equality, lost its way and ended up in Marikana.

Miners Shot Down is a chilling account of the events that led to what has been dubbed the Marikana massacre, using video footage and interviews from the seven days in which miners were striking for better wages.

“I thought it was very important to attempt to set the record straight, to show people what happened and in the process of showing people what happened you begin to understand why it happened,” he says.

Desai was born into a politically active family. His father, Barney, was a leader of the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) and the family had to flee South Africa in 1963. Desai grew up in Britain but his parents constantly reminded him of his roots. While still a teenager, he joined his father in politics, passionate about fighting racism and capitalism. Both returned to South Africa in 1990. Rehad became a trade unionist with socialist ideals but after his father died, he ventured into television and film producing. To date, he has a string of documentaries to his name, many of which have garnered international acclaim for human rights.

His latest film is a story of working class South Africans that have been failed by their government, a government they believed was on their side.

“I think the revolution is coming back, the question is will there be a mature enough leadership to lead it or will the ANC, our ruling party, be mature enough to lead it, to be able to address the very real issues that this country faces or will they continue to follow the same path where the bulk of our people are excluded from the benefits?” asks Desai.

He is steadfast that the shooting on that fateful day was no accident, no measure of self-defense, but a conspired action to eliminate a problem. The film pieces together footage not seen by the public, scenes of the days before the shooting.

“It didn’t just happen, there were events that led to the shooting,” says Desai.

Horrific scenes of dead miners lying on the ground gives you an instant jolt back in time to the attacks carried out on innocent black people under apartheid, children scrambling for safety from gunshots. Desai admits that miners retaliated, but only after they were shot at first.

“Just as they were nearing their informal settlement, a number of vehicles moved in quick succession to sort of box them in, block them off and as that happened and as the miners drew nearer, teargas was fired at them, birdshot and rubber bullets, one of the mineworkers got his pistol out and fired back.”

This was the scene captured by television crews, played out on screens across the world, leading many to believe that the police fired in self-defense. But, Desai wants to know why police had live ammunition and why they had 8,000 rounds of ammunition that day. It is a question that is still being probed by the Farlam Commission of Enquiry. For Desai, it is clear cut; someone from the top gave the order.

Desai’s film takes a poignant look at the ANC as a movement and ruling party over the last 20 years, by following Cyril Ramaphosa.

“Cyril’s story from the 1980s, tells the story of the ANC, a movement which was heroic, courageous, vibrant, responsive, democratic which led a struggle against a white minority regime and succeeded,” says Desai.

Ramaphosa, once passionate about worker’s rights, formed the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) in 1982. He later became a politician serving under Nelson Mandela. He left in 1999 to become a successful businessman, returning to politics in 2013.

At the time of the Marikana shooting, Ramaphosa was a non-executive member on the Lonmin board. The Marikana mine belongs to Lonmin.

“With the political kingdom the ANC gained, they lost sight of the bigger issues related to our economic democracy and we can see that story encapsulated inside the life trajectory of the man who’s become the deputy president of the ANC,” says Desai.

In March, Miners Shot Down was released at the One World film festival in Prague. The film took top honors, winning the Vaclav Havel Jury award for its exceptional contribution to human rights. It also won the Camera Justitia Award at the Movies that Matter Festival in the Netherlands.

The documentary is part of an ongoing campaign for justice by the miners and their families. They want the police to be prosecuted. Instead, miners are facing murder charges for the police that were killed. Explosive evidence recently emerged at the commission about killings committed by mine workers. Witness accounts of atrocities committed by Amcu members, attacks on their fellow members for defying strike orders, the brutal mutilation and murders of police and of members of the rival union NUM. The commission expects to continue for some time as more new evidence comes to light.

The latest evidence again raises questions, what kind of struggle is this? No doubt there will be more stories to be told about Marikana.

Loading...