For days, it had been tense in the cells beneath the Palace of Justice in Pretoria, in an eight-month trial punctuated by fear, loathing and laughter. For Nelson Mandela and his co-defendants, it was to prove a harrowing dance with the death penalty. Mandela was convinced he was going to die, according to his fellow defendants, and had started passing on his wishes to his fellow accused Denis Goldberg.

“He thought he was going to hang,” says Goldberg.

There was a good chance that they were going to hang. All were charged with sabotage against the apartheid regime. It was an accusation so serious that, if the prosecution proved a case to answer, the onus was on the accused to prove innocence—rather than being innocent until proven guilty.

The ambitious prosecutor, Percy Yutar, laid on the evidence with a shovel. He painted Mandela and co as desperate terrorists who had enough explosives to blow up Johannesburg. In giving evidence, Yutar would occasionally turn and smile to the special branch men in the gallery. Goldberg recalls how the special branch men would look at him and draw a finger across their throats in a threat of death. Goldberg gestured back with a jerk of the middle finger.

The antagonism worsened. Yutar ventured to the calm intellectual, Walter Sisulu, that life for the black man in 1960s South Africa was not all that bad.

Loading...

“I wish you could live for just one day as we are forced to do and you would not make such a remark,” flashed back an angry Sisulu.

There was laughter when Ahmed Kathrada, one of the three survivors of the trial, gave evidence in the witness box. He was asked about a man, clearly him, referred to in evidence merely as ‘K’. He was asked did he know anyone with a name beginning with the initial K?

“Khrushchev,” replied Kathrada, referring mischievously to the Soviet premier of the day to the laughter of his fellow accused.

It all led to one moment that was to transform the public perception of those in the dock from terrorists to freedom fighters—the Benjamin Franklins of Africa in the eyes of the world press, in the words of defence team member George Bizos. To kick off the defence, the accused had opted for a statement from the dock. Mandela led the way with a speech that took six hours and went down in history.

“I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons will live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to see realized. But my Lord, if it needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The late Arthur Chaskalson, then a young member of the defence team, told me in 2010: “There was a dramatic silence you could almost hear the silence in the court, you could feel it. It was absolutely quiet, not a sound.”

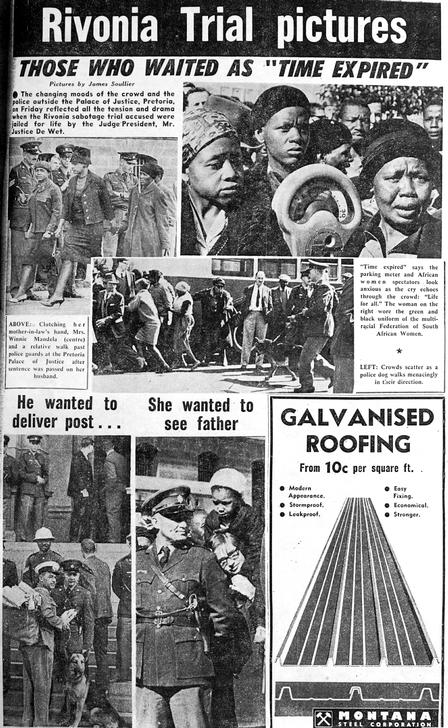

When the accused came up the steps to the court on June 12, 1964, they still thought they were going to hang. What they didn’t know was that a combination of the prosecution’s failure to press the case, diplomatic pressure and reluctance by the authorities to make martyrs out of them, was to save the necks of the Rivonia trialists.

When the judge almost whispered a life sentence, instead of death, the relieved trialists looked at each other and laughed out loud.

“Life and life is wonderful,” Goldberg says to his mother in the gallery.

More than 30 years later, Mandela, in one of his many shining acts of reconciliation, invited Yutar, the man who tried to hang him, to tea.

A few years later, Mandela opened the Constitutional Court in Johannesburg, on February 14, 1995, that was to be led by Chaskalson. The next day, the court was to debate the death penalty and Mandela knew this was a moment for his impeccable timing.

“The last time I appeared in court was to hear whether or not I was going to be sentenced to death. Fortunately for myself and my colleagues we were not,” says Mandela.

“If he had been executed what would have happened?” asks Chaskalson in 2010.

I dread to think.

Loading...