Munhava, an area in Beira, Mozambique, is tense. The protests begin at midday with burning tires and the opening of the first shebeens. Acrid smoke hazes across the sky in the searing heat. By 2PM the mob has resorted to violence

Now, in the humidity of dusk, it is eerily calm as we wait patiently for darkness and the first wheezes of diesel generators from the more upmarket dwellings in the near distance.

The air is rich with fried fish, excrement and kerosene. A vivid stench of poverty framed by the sea. Across the slum, in a small landfill, scavengers rake over debris and waste before burning the rest. The laundry swinging on the line in front of me is trackmarked with soot.

A small riot on the ragged edge of Mozambique’s second largest city may not seem like a big deal but the dispute, aimed at the local municipality, was over what is arguably the most contentious issue facing African slums today—electricity.

It echoes a pattern of unrest we are seeing from Kibera in Kenya to Khayelitsha in South Africa and across the Sahel. Electricity is fought for and fought over in the poorest corners of the world. All around us in Munhava, makeshift cables and wires hang dangerously from tin shacks, so tightly packed they blend into each other. For those without the savvy to misappropriate electricity from the local provider, EDM, there is little option but unreliable and inefficient sources of energy. Somali store-owners pile their wares high with firewood, charcoal, candles, kerosene, battery-powered flashlights and palm oil. The deeper scandal is evident on these humble wooden counters across which the poor hand over the little they have for scant solutions. According to some estimates, the poorest of the world pays 20% of the world’s lighting bill, but receives only 1% of the benefits.

Loading...

Kerosene and paraffin swallows 25% to 30% of a family’s income in Munhava. There are other costs too. Across from where I sit, the one-room shack, lit by kerosene at dusk, will probably have concentrations of pollution up to ten times the level that is considered safe.

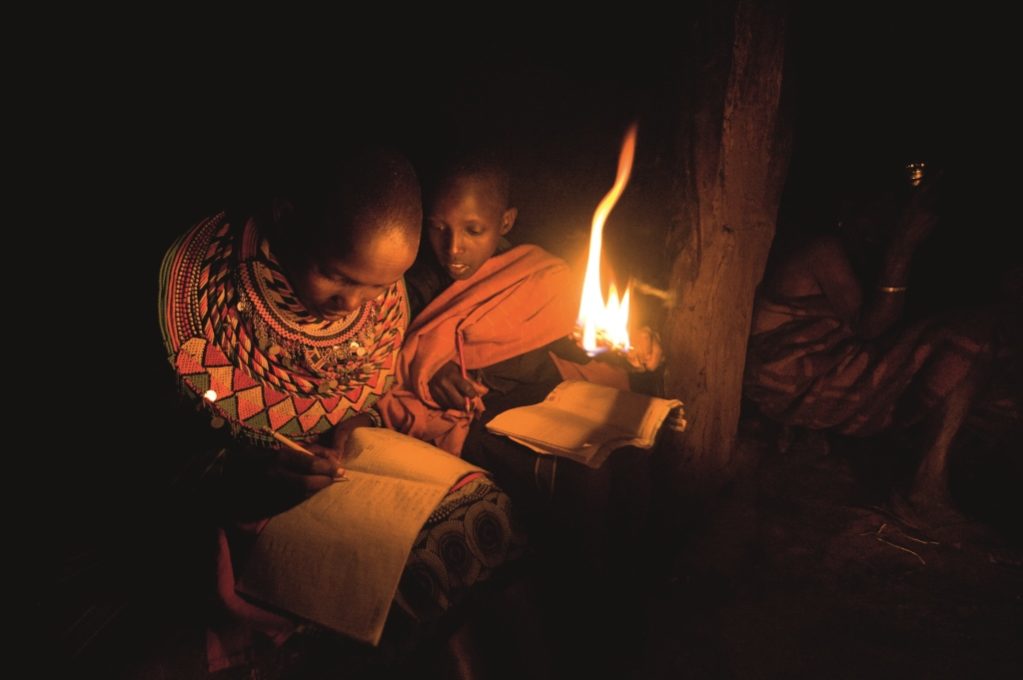

At dusk each day, throughout sub-Saharan Africa, some 600 million people, or around 66% of the region’s population, prepare for the darkness and life without electricity. In rural communities, that number climbs to a remarkable 85%.

Sipping a warm beer from a broken refrigerator, I reflect that darkness has dogged even my recent travels across the world. On the road into Beira, I reflect on the need for mainstream debate around energy poverty in Africa.

Energy is needed to reduce the world’s greatest child killer, acute respiratory infection. Up to 1.6 million people worldwide die from exposure to excessive levels of smoke in their homes from cooking fires. A quarter of all these deaths occur in Africa.

When I travel across Africa and ask people from all backgrounds what they need from electricity, the answer is often as simple as a light at night or a simple stove.

Yet when I sit in squatter homes in Kinshasa, where power is available but subject to rolling blackouts that can last days and weeks, and ask the same question, I am given insight into the new Africa. There is a need to power laptops, televisions, refrigerators and air conditioners.

No two situations are the same in Africa. But whose needs get priority? It appears the latter, the aspiring consumers. Today, the direct link between economic growth and electricity on the continent is finally placing this issue on the international agenda.

Last year, the United States president, Barack Obama, launched Power Africa, an initiative that will commit $7 billion over the next five years to support the energy needs of Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Nigeria, and Tanzania.

The human cost of work productivity in Africa due to the lack of access to electricity cannot be underestimated. If a population lacks adequate access to power it blocks any significant economic progress and in turn stability. It’s an issue that makes me think about the burgeoning youth population. With the competitive edge that technology provides, unreliable access to electricity hinders African youth.

Today, young people in Africa make up almost 40% of the working population, yet 60% are unemployed. Increasing energy access has the potential to boost sustainable development, as well as build human capital on the African continent. Without electricity, hopeful entrepreneurs are not able to gain access to market information and technologies to expand their businesses and schools are not able to prepare students for a knowledge-based economy.

In many ways, Africa has two key energy problems: there are many millions of people who have no grid extended to them, and won’t have in the foreseeable future, and the energy production in most countries is insufficient to meet the demand of those already on the grid, let alone those not yet connected. That is why power failures are so common in developed Africa.

But what are the solutions? Accelerating access to energy, particularly clean, renewable resources such as wind, water, the sun, and biomass among others, is ideal. It reduces pollution that contributes to climate change, while promoting Africa’s productivity and economic growth.

Such initiatives have the potential to make a difference in the lives of millions of Africans but it still isn’t enough. Collectively, the private and public sectors must work together more to strengthen Africa’s technical infrastructure to expand access to energy.

Everywhere, I read of radical solutions, from oceanic wind farms to mass solar power programs in the Sahara and hydropower on the Congo River to a scheme initiated by Harvard University alumni to extract energy from ordinary soil.

Some investors are backing jatropha, a plant whose seeds produce an oil for burning in generators. There is also an effort to tap geothermal energy. The Great Rift Valley, from Eritrea to Mozambique, could produce 7,000 megawatts. Kenya hopes to get 20% of its energy from geothermal sources by 2020.

To understand the existing and realistic scope of alternative energy solutions, I recently visited the Bisasar Road landfill site in Durban, South Africa. I was there to produce a short film around a project that converts landfill waste, a form of biomass, to methane gas and in turn electricity.

In Durban, trash is quietly and effectively making enough energy to sustain 3,800 households. Peter Seagreen, the sprightly 74-year-old mechanical engineer in charge of the Durban site, says converting trash to electricity would have been beyond imagination when he was growing up as a ships engineer. Bounding around the site like a teenager, he marvels at the technology at his disposal but bemoans the lack of knowledge around its potential.

“We are converting rubbish into electricity yet the local community barely realizes we can achieve this. It’s a miracle if you ask me. It also makes me wonder why this is not being expanded across Africa. We are the only ones doing this, yet Africa isn’t short of landfill waste.”

Arguably the most exciting thing about the prospect of creating electricity from gas is the dividend it could provide for gas-rich nations like Mozambique, Tanzania and potentially South Africa. The possibility of gas pipelines powering and empowering remote communities with electricity from similar turbines is attractive. It is a game-changing dynamic that could liberate rural areas.

Of course the argument between robust and pragmatic solutions to energy poverty, and the role gas could play in it, are tempered by the debate around global warming and fossil fuels.

But, time is not on our side. Over the border from Mozambique, in Malawi, the booming charcoal trade is relentlessly damaging the nation’s reputation as an evergreen country. Malawi has the highest deforestation rate in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) region. The disappearance of forest cover has also resulted in massive soil erosion and siltation in low-lying areas, leading to flooding that has been disrupting operations at Malawi’s biggest hydroelectric dam, the Nkula Hydroelectric Power Station.

Then again, in Malawi and elsewhere in the SADC region, charcoal’s attractiveness to impoverished locals is not difficult to understand. A sizable bag in an urban area costs around $7. For an average family of seven, this might last them nearly a week, but if they were to use electricity for all their cooking and heating, they would probably spend more than $15 during this time. Not to mention the high cost of electrical cooking appliances such as hotplates and heaters. A new hotplate costs around $30, beyond the reach of ordinary Malawians, most of whom live below the poverty level of $2 a day. In contrast, charcoal stoves, made in China, are around $2.

What the success of the Durban project shows us is that we should be looking towards expanding energy solutions that are already in place. Landfills, often in the heart of African cities, form a center point for the poorest of the poor. Using them to generate electricity, a proven science, could open the door for other more practical solutions.

Today, the fundamental obstacles to energy have been researched and established. The barriers, while complex, can be overcome, and international co-operation can help. Technology is also on our side. We do know how to build power systems and meet energy demand efficiency. What is required is a political prioritization. Energy access must become a continent-wide priority.

Innovation could provide the best chance we have to transform the energy landscape but it is also sobering to think that around 90% of the world’s designers, our greatest minds, spend all their time working on solutions to the problems of the richest 10% of the world’s customers. What if they were to use their expertise to solve the greater problem in the developing world?

African townships draw in and absorb young people from rural areas. They are also places of unbridled ambition and hope, not necessarily idleness and squalor.

In ‘Shadow Cities’, a book that describes a tour of slums across the globe, Robert Neuwirth recalls that New York’s Upper East Side was once a shantytown. He suggests that all cities start as mud. But, in the modern connected technological world we know, the odds are stacked against the slum dwellers when there is no energy to power ambition.

Loading...