“And the Oscar goes to…”.

Five little words that caused writer and director Bryan Buckley to draw a deep breath:

“When you hear those words… and you happen to be one of the five guys it could possibly go to, it is, in itself, a crazy thought. It simply just doesn’t seem real. All the films could have easily won that night. And mentally you know this going into the evening. If I didn’t think we had put everything we had into our film, perhaps I would have been disappointed in myself and thought about what we didn’t nail in the film when the winner [Curfew] was announced. But I knew this wasn’t the case. It just wasn’t our night,” says Buckley.

Bryan Buckley and Mino Jarjoura with Harun and Ali Mohamed, on the red carpet

He was in Los Angeles, California, at the 85th Academy Awards, where he was nominated for best live action short for ASAD—a tale of refugees, in Somalia. Sitting nervously by his side were the two leads, 14-year-old Harun Mohamed and his 12-year-old brother Ali. The day had flown by, moments before they were walking the red carpet alongside the A-listers—including Ben Affleck, Daniel Day-Lewis and Ang Lee—and doing interviews.

Loading...

“The BBC was the first to interview the boys. Harun stepped forward to the microphone and began to talk about his journey in English. How far he had come, had never been so apparent. He and Ali were constantly asked what celeb they wanted to meet the most at the ceremony. And without question Harun would say Jackie Chan and Ali would say Jean-Claude Van Damme,” says Buckley.

It was a journey that began with the filming of ASAD in Africa.

Buckley is the last person you would expect to make a film about Somalia. His business is big-budget Super Bowl (American football) commercials for a quarter of a billion dollars with an audience of more than a million. Conversations with Somali refugees motivated him to create the short film with little commercial value or audience.

It all started in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, in 2010, where Buckley was shooting a documentary called No Autographs for the UN Human Right’s Council. He left with that feeling of hope in the face of despair. A year later he wrote ASAD.

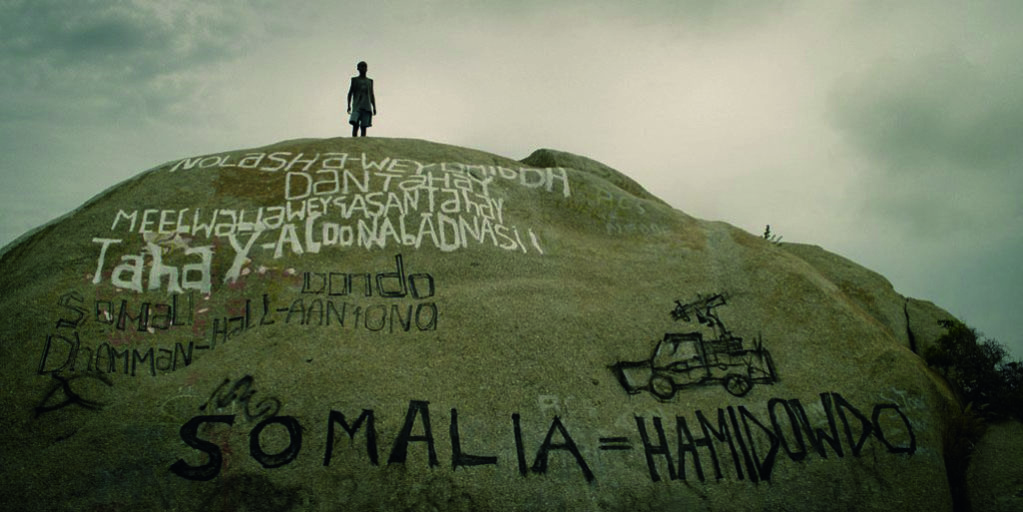

The film was set in Somalia and shot in Cape Town. It tells the story of a young boy who must choose between life as a pirate or that of a humble fisherman. The entire cast was made up of refugees who had fled to South Africa.

Buckley says the biggest problem in producing the 18-minute short-film was overcoming the language barrier as both leads, Harun and Ali, were illiterate.

“We knew language, with the whole cast, was going to be a barrier by virtue that we were doing the entire film in Somali and I didn’t speak a single word of it. Right off the bat we enlisted in two Somali translators [who helped the boys memorize the script]… Both the boys are exceedingly bright. They picked up on things so quickly it was crazy. And then I’d act out some stuff and they would study it and follow. Always bringing their own twist. of course, like any Hollywood star would.”

The filming was taxing and Buckley struggled to shoot scenes with the rebels.

“There was just so much emotion there between them [the rebels] and the boys. It was quite clear this wasn’t the first time these refugees had handled guns. I kept thinking what horrible ghosts were haunting them after every take. And how bizarre [it was that] our cameras were recording every second of this nightmare.”

The international acclaim came with praise from Somali musician K’naan.

“He is truly a man who has supported Somalia and its people’s plight more than anyone I know. He said, ‘ASAD is an important film. It makes human the inaccurate caricature of Somalia, showing real people, a community and life beyond a land of pirates and warlords,’” he says.

The film won numerous awards at various international film festivals, including the Tribeca Film Festival and San Jose Film Festival. The Academy Awards nomination was the cherry on top but the leads almost didn’t make their big moment in Hollywood.

“The fact that they [Harun and Ali] didn’t have travel documents and that they were Somali refugees did not help matters. ASAD’s producer Mino Jarjoura worked around the clock with [South African producer] Rafiq Samsodien to get the kids there. It took government officials from both the US and South Africa, along with UNHCR to pull off the task. And they did so, in dramatic and perfect timing.”

Regardless of the outcome the team celebrated making it to the Oscars with a toast. After the ceremony they attended the prestigious Governor’s Ball.

Buckley may have walked away empty-handed but he and his two young leads stood tall for one of Africa’s untold stories.

Loading...