The story goes that in 1867 a 15-year-old Afrikaans boy picked up a ‘mooi klippie’ (nice stone) on the banks of the Orange River in the Hopetown district. Sir Roderick Murchison, Keeper of the Royal Museum of Geology in London, said the diamond had been planted. It was impossible, he said, for diamonds to be found where it was, but soon massive diamond deposits were discovered in Kimberley and the Hopetown district and the diamond rush began.

Syndicates and partnerships were set up, the De Beers Group being the largest. They were in favor of the Diamond Trade Act of 1882, which made it a punishable offence for anyone, but a licensed buyer, to possess rough diamonds. A diamond cutting industry, they believed, would pave the way for stolen diamonds to be processed.

However, in 1919, the then-prime minister Louis Botha, put forward a plan to start a diamond polishing industry. A Cutting Act was passed, but it was another five years before an industry was established in Kimberley. Dutch experts were imported to train local workers and diamond polishing began in earnest.

But the trade went through a series of recessions and did not prosper. Eventually most of the industry moved to Johannesburg. In 1930, a Diamond Workers’ Union had been set up, but the trade suffered in the Great Depression and really only recovered during the Second World War.

Loading...

The master cutters formed a Diamond Dealers Club, which remained stable and productive contributing to the fiscus and being respected around the world. In 1947, they were admitted to the World Federation of Diamond Bourses in Antwerp, Belgium, but the changing political situation in South Africa had its effect on the trade.

In 1976, the master cutters wanted to introduce a chain system—a way of polishing the rough stones in a production line—a faster method of producing a finished diamond. But the polishers objected to this because it lowered their skill. They went on strike. After six weeks, the chain system was brought in anyway.

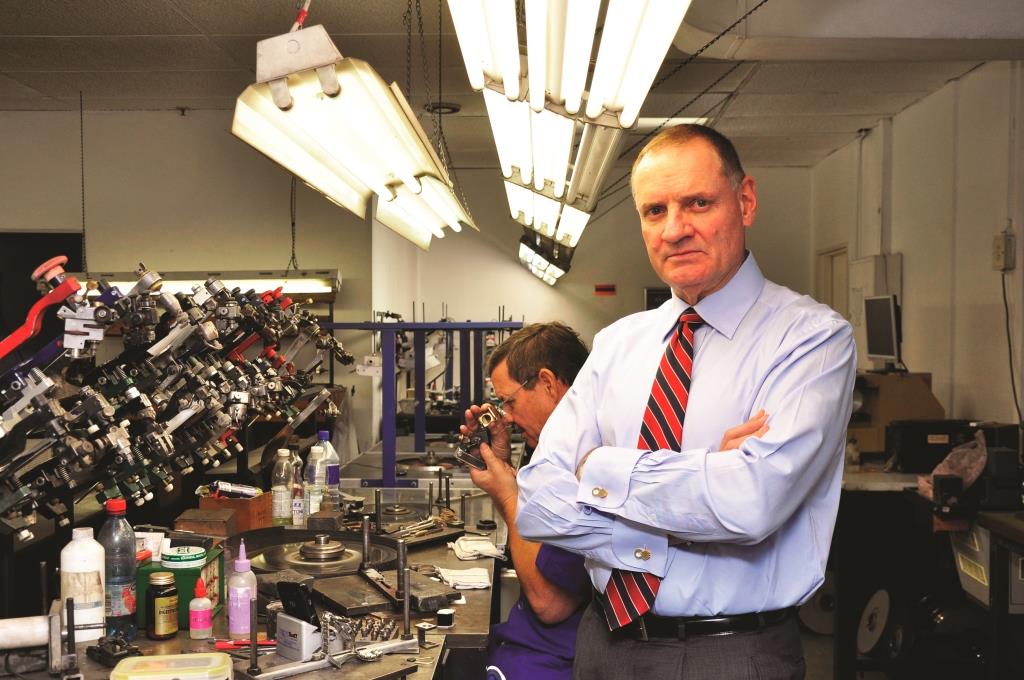

Ernest Blom, then 25, was the youngest vice-president of the Diamond Workers’ Union. Initially, the fewer than 1,000 diamond polishers were exclusively white. After the strike, women and previously disadvantaged individuals were admitted as polishers and the tradition of a five-year apprenticeship was abandoned.

The Harry Oppenheimer Diamond Training School opened with Blom as its first chairman. The idea was to train unemployed youths. The South African Diamond Bourse sponsored the school, but the new diamond cutters were no longer artisans in the accepted sense of the word. By 1990, the trade reached a peak with 3,500 workers and 18 sightholders—those factories entitled to buy rough diamonds directly from De Beers.

By July, the number of sight holders had fallen to 10—none of them South African. The number of diamond polishers had dwindled to less than 600.

Blom says the European banking crisis and recession have affected the trade. The local industry has suffered with the declining labor force, the competitiveness of Indian and Chinese buyers and too much red tape.

“Our production costs are too high, much higher than Indian or Chinese costs. The open system of buying rough directly from the diggers has gone, having been replaced by the tender system which most people accept,” says Blom.

A Johannesburg factory owner said: “De Beers did not look after the local industry, nor does the government. Many workers are being brought in from India. They work seven days a week, virtually 24/7, non-stop, are housed in crowded conditions and bussed to the factories. Furthermore, they are paid in India, so they pay no tax here”.

“Uncut diamonds, which now have to be bought through the State Trader, are too expensive because our labor costs are too high. It’s more profitable to send rough diamonds overseas for processing, despite the taxes and interminable red tape.”

Another factory owner said the government wanted diamond polishers trained locally.

“We are just not able to buy polishable goods at workable prices [to train them on],” he said. “What’s more, there are qualified workers who are unemployed, walking the streets, trying to get jobs, so how can we take on learners?

“In any case, the industry is moving to Botswana and Zimbabwe. At this rate, there is no future in this country for a polishing industry. There isn’t one wholly South African-owned sightholder. There is a 500-bench factory in Polokwane and they cannot get a sight.

“The only hope is to give rough to South African-based manufacturers at a favorable price. South Africa was once regarded internationally as being at the forefront of diamond polishing—now it’s a joke.”

Blom was sanguine, however.

“The government is due to hold a summit later in the year. Hopefully, they will upskill labor and cut out the unnecessary red tape. If they get that right, we still have a bright future.”

A Diamond In The Rough

Kgele Ellen Mahuma finds herself in the heart of the African diamond industry and still can’t believe how she got there. It’s been a long way since her childhood years, when she first recalls watching a dishwashing liquid commercial on television: the dishes sparkled like diamonds. Mahuma also remembers the advertisements for diamonds and how she longed to touch them. Her childhood dream became a reality in 1984, now she has her own diamond cutting, polishing and trading company.

Mahuma is multi-talented: a true diamond in the rough. She established K. E. Mahuma Diamonds—with its modest office in the South African Diamond center, in central Johannesburg—in 2008. In the next two years, she hopes to have an employee or two.

“I don’t want to rush things, it must grow first. The money I could pay that person, could have bought a stone. I can do everything on my own,” she says.

This diamond entrepreneur has repaid the loan used to establish her company. She visits her clients from China to India and from Dubai to Belgium.

It’s a lucrative industry.

“If I have a polished stone, there are always buyers,” she says.

It can be a risky one too.

“It’s a dangerous industry. My neighbors don’t even know what I do. They try to investigate. They ask my children, ‘Why is your mom going to China? ’I tell them, ‘I work for a white man and I am happy with my job.’”

There is a lot of worry around the buying of stones. She bets against around 100 other people; the person who offers the highest price, ‘wins’ the parcel.

“Whenever I ‘win’ a parcel, I worry that I may have overpaid and miscalculated because I have to consider the color and clarity of the stone or stones; as well as my labor; the payment for the certificate from the lab and then, of course, the profit I will make,” she says.

She started working for Reichman Diamond Cutters in 1984, at the age of 23. It took a year of training to learn the basics of the trade and another five for her to feel competent.

Her mother—who used to work at the bioscope (cinema) in Carlton Center—was scared when Mahuma first started working there.

“She used to say, ‘don’t lose any of the diamonds. Don’t tell anyone that you work there. Don’t let anyone convince you to steal one’,” she recalls.

It wasn’t easy for a Zulu-speaking woman. The male to female ratio was two to one. She was the only black woman at Reichman Diamonds; there was one other black man working alongside her. Her mentors were Afrikaans-speaking, colored males.

“They couldn’t speak my language. I was forced to learn and speak Afrikaans. I used my dictionary at home and if I couldn’t understand something at work, I had to ask someone to explain it. Now I’m competent in both,” she says.

She has trained seven other black diamond cutters on a part-time basis; two men and five women, three of them are foreigners: one from Côte d’Ivoire and two Ghanaians. While she doesn’t charge them the going rate of R30,000 ($3,550) for a six month training course, her trainees can recognize a sure-sell stone and sell the diamonds bought in their home countries to her.

In a month, she polishes around six stones amounting to around 14 to 16 carats.

While she believes the South African diamond industry is growing, times can be as rough as the diamonds.

Loading...