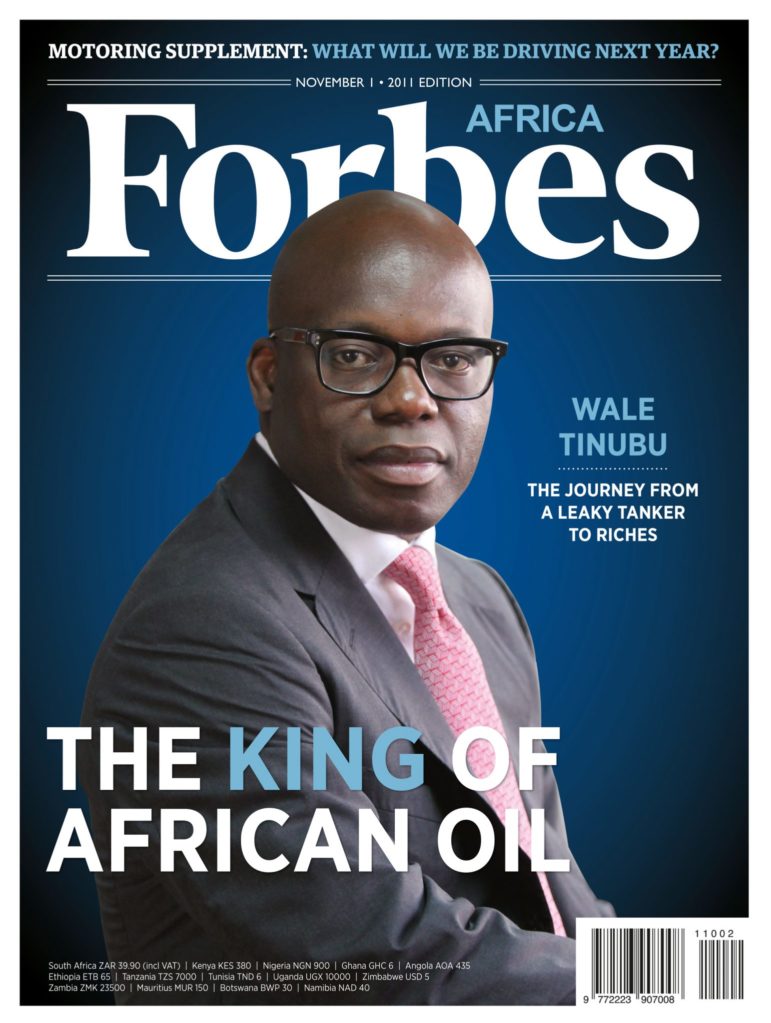

It is past three o’clock on a summer afternoon in Victoria Island, Lagos. Wale Tinubu, dressed in a dapper white shirt and donning thick, black-rimmed nerd glasses, is seated at the desk in his sprawling office on the 10th floor of the landmark Zenon House building. He is scrutinizing reports, signing cheques and receiving phone calls at five-minute intervals. He looks every inch the head of a $1 billion energy conglomerate. He smiles at the Forbes Africa team as soon as Oando’s Head of Corporate Communications ushers us into the room.

“Ah, the Forbes Africa guys,” he enthuses. “You’re welcome. Please make yourselves comfortable.” Of course, we do. The walls are painted a vibrant blue; across the tiled floors of the sprawling working area is a huge set of windows providing a panoramic view of the city’s glistening skyline. Far to the right of Tinubu’s desk, there is a huge office shelf full of numerous awards, plaques and various laurels. A framed picture of him shaking hands with the mythical maverick business intellectual, Jack Welch, occupies pride of place at the pinnacle of the office shelf.

Tinubu is inspired by the former General Electric boss. This much we know. But aesthetics aside, it is difficult to catch Tinubu in the same place for long; he’s always on the move: London today, New York tomorrow, Paris the next. You know the type. After being on his trail for several weeks, and exchanging numerous phone calls and emails with his corporate communications staff, our persistence paid off. We were finally meeting with one of Africa’s most storied oilmen.

In case you were unaware, Tinubu is the group chief] executive officer of Nigerian energy giant, Oando. Oando is a Pan-African energy corporation with operations actively spanning all aspects of the energy value chain, including the marketing and distribution of refined petroleum products, exploration and production, refining, and power generation. Oando is the largest non-government owned Energy Company in Nigeria and has a market capitalization north of $1 billion. It is the first Nigerian company to achieve a dual listing on both the Nigerian and Johannesburg Stock Exchanges. Tinubu has made himself Nigeria’s most venerable energy tycoon and inserted himself atop the pecking order in the major league of Nigeria’s oil industry.

Loading...

Tinubu’s vision shaped Oando. So did his relentlessness. Forty-four-year-old Tinubu is apparently very proud, almost to the point of being cocky, of how much his company has achieved. “Our business started 17 years ago as a very small service company delivering fuels to the upstream service providers, and it has grown to become the largest indigenous oil and of multinationals operate here, but there are very few indigenous oil corporations that span the downstream, midstream and upstream like we do.” When he divulges that the group’s revenues hit the $3 billion mark in 2010, he says it flippantly, almost detached– like $3 billion is pocket change.

Tinubu’s characteristic composure and demeanor makes it seem like success has been easy. But it hasn’t always been this way. Oando’s early beginnings were humble. While Tinubu easily comes across as Nigeria’s most powerful energy entrepreneur today, his initial ambition was to be a lawyer. As the story goes, at the age of 16, he left Nigeria to study law at the University of Liverpool in England.

It’s easy to argue that his initial fascination with the legal profession stemmed largely from the fact that his father was a successful lawyer and managed a thriving legal outfit at the time. His winning streak in business kicked off at Liverpool. As an undergrad, he used to travel to Europe to buy luxury cars, using his school fees as capital. He then drove the car through Europe and back to London, trying his best to flip it off for a profit enroute. He usually succeeded. Tinubu was only 21 at the time, but he had already started making substantial amounts of money. He probably never realized it at the time, but it was the genesis of what was to be a successful career in deal making.

After his first degree, Tinubu earned a Master’s in Law from the London School of Economics at the age of 22. In Nigeria, lawyers are required to attend law school for a year before they are allowed to practise, and so Tinubu had no option other than to return home to his motherland.

After law school, he started out as a lawyer at his father’s firm. It wasn’t long before he realized that the legal route was not for him. It was too slow paced, too drab and unexciting.

Tinubu, a sucker for challenges, decided that he wanted to launch his own business. He wanted to be in charge and in control. Tinubu set up his first office in his father’s garage. It was modest, to say the least. He gave the garage a facelift, buying a second-hand carpet, painting the walls and installing a telephone he had borrowed from his father’s house.

On the first day, he sat down in his little garage-cum-office, ready for business while trying to figure out what business he was going to do. To stay afloat, Tinubu broke even by handling small corporate legal jobs right from his garage office. As time went on and as he generated income from small corporate assignments, he vacated his modest office in the garage to a more expensive office, albeit in the same street. He had used up almost all the money earned from his small jobs to rent the place. Tinubu continued with his legal practice, until the opportunity he had been waiting for came knocking.

A friend, Jite Okoloko, who would later go on to become an executive director at Oando, had been offered a rather lucrative contract by Unipetrol, a government-owned oil company, to transport diesel from a government towned refinery in Port-Harcourt to fill up fishing trawlers in Lagos. Okoloko was looking for a vessel to transport the diesel.

Coincidentally, Omamofe Boyo, a close friend of Tinubu, who was also a lawyer, represented an oil services firm which owned a 1945 World War II tanker–The Carolina–Tinubu realized they could charter the ship to fulfil Unipetrol’s requirements. Tinubu set out with Boyo to inspect The Carolina at Bonny Island, which is located at the edge of Rivers State in the Niger Delta. The ship was anchored offshore and the weather was as unfriendly as it could get. Tinubu’s eyes light up as he recollects the episode. “It was raining heavily.

We were on board this outboard engine speed boat that was moving at tremendous speed–I think it was 60km per hour–and all we had was a rain sheet over our heads. And I was asking myself: “What the hell am I doing here”, because we had no life jacket. The canoe was bouncing up and down in the lagoon, the weather was so bad. But then, when I saw The Carolina ahead of me, I just knew it was my destiny in seconds.” When the two friends went on board the boat, they were surprised to find that the crew members were peeved. Apparently, they hadn’t been paid for months by the ship’s owners, and their general welfare had been neglected. They were disconcerted and they showed it; they were not ready to work. A mutiny, rather than a delivery, was more likely.

But Tinubu and his partner, ever the dealmakers, put their negotiation skills to play. They calmed the crew down, massaged their ego, and paid them N50,000 ($104) on the spot. Tinubu offered to charter the ship and promised to tend to their welfare needs. By now, the crew were excited and ready to work with Tinubu. But chartering the ship was not cheap. It cost thousands of dollars and Tinubu did not have the money. He turned to his parents, who loaned him $10,000 to charter the ship. With the money in hand, he was good to go. He informed his friend, Okoloko, that he had a ship to transport the fuel.

“The Carolina was an old lady, she did five knots of speed every time she was loaded, and when the tide was against her she would go backwards, but she always delivered in the end.” Tinubu kept transporting diesel for Unipetrol. It was a lucrative venture and he was enjoying every minute of it. Tinubu should have been making money hand-over-fist, but in reality, he was struggling through not getting paid on time. He was to learn that the larger companies had a tendency to drag their feet when it came to paying up.

Tinubu was at the receiving end–the victim– and his debt was piling up. He didn’t even have enough to pay for the charter of The Caroline. “We didn’t know there was something called trade account receivables, that when you sell something you didn’t get the cash. Particularly the bigger the company you work for, the longer it takes for them to pay you. And so we had lots of bills pending, and the bills wouldn’t be paid to us and I used to have difficulty paying them their freight,” he says. As Tinubu’s debts increased, the ship owners became more impatient with him.

One day, he summoned up the courage, approached the ship’s owners, and made a rather audacious suggestion to them. “I said to them, rather than us owing you money, why don’t we just buy the tanker from you on credit and then you know that at least you sold it and you made a profit.” Tinubu takes a moment to smile at himself in retrospect. “I thought it was perfectly logical. Someone might think its a bit cheeky today, but I thought it was a logical business decision to make because at least they stood to crystallize their profits.” A price tag of $100,000 was agreed.

Once again, Tinubu didn’t have the money, but he was not going to be deterred. This was an opportunity he could not let slip through his fingers. He was determined to buy the ship and blow the consequences. In his bid to raise funds, he approached a small finance company for the loan. “It was not a bank; it was a finance company. The finance company was staffed by three people who had the credit to get loans from the bank and in turn, loan us struggling businessmen. We were all downstairs waiting for money. I got the money, and I was very happy that someone could lend me money. That inspired me to deliver.”

With $100,000 in his pocket, Tinubu bought the ship. It was a defining moment in his life. He no longer owed the tanker owners; he now merely owed the finance company and he had to pay back the loan at high interest: 10% a month. Tinubu set out to repay his debt. It wasn’t easy. The oil trading business at the time was even morestrenuous than it is today. “There were obstacles; we didn’t have credit, we didn’t have cash and we didn’t have the transfer system.

I remember many times carrying a million naira on my back in a duffel bag. In those days there were only N50 and N20 notes, and it was so heavy, but there were no transfer systems, and I had to physically carry duffel bags full of cash, sitting in the planes–old planes that were shaking in turbulence–from Lagos to Port-Harcourt to go and pay for the port charges so that I could get my ship loaded. And then the ship would sail, I would hold the bill of lading, get on a plane, fly to Paris, cash there and then turn around the next day and fly right back to Lagos. I would change the money into naira, and then carry my duffel bag and go back to Port-Harcourt.” Despite the toughness of the oil trading game at the time, Tinubu’s small oil trading operation prospered. The Carolina proved to be a smart acquisition for, as Tinubu says, “It was profitable and it made its value every month”. Before long, he had paid off the $100,000 loan.

As Tinubu’s company Ocean and Oil grew in stature, modest success followed. Tinubu’s company grew its fleet from one ship to two, three, and then seven ships. Within a few years of operations, Ocean and Oil had become the undisputed leader in the supply and trading of fuel products. And Tinubu, who was barely 30 at the time, savored it all. The biggest opportunity was yet to come. In 2000, the Nigerian government, through the Bureau of Public Enterprises (BPE), sought to divest its shareholding in Unipetrol, a leading petroleum marketing company.

Unipetrol had been floated on the Nigerian Stock Exchange in 1992, and the government owned 40% equity, while the remaining 60% was held by the Nigerian investing public. By 2000, the government had decided it was going to divest its shareholding by selling 10% to the public and 30% to a strategic private investor. The government called for bids from prospective investors. Tinubu and his two friends, Mofe Boyo and Jite Okoloko, decided to bid.

The price of the 30% stake was put at $16 million. Even though Tinubu had already started raking in substantial profits from his oil trading business, he did not have that kind of money. But it’s not in Tinubu’s nature to be deterred. The three friends put in their bid for the stake, and held their breath. Tinubu and his friends were barely 33 at the time, yet they were seeking to gain control of one of Nigeria’s largest petroleum companies. The odds seemed stacked against them. Tinubu was daring to achieve the impossible, particularly in a country like Nigeria where concrete political connections are almost a prerequisite for winning lucrative tenders and acquiring government-owned assets. Here was Tinubu and his team, barely 35, withoutany political connections, attempting to acquire a government-owned petroleum firm.

Tinubu’s energy is infectious; and so on theday he presented to the panel of the BPE, they were extremely impressed. Tinubu and his team clearly had a well-articulated plan for the company, they seemed smart enough to run a multi-million dollar company and they were driven to succeed. Tinubu and his team won the bid. But the celebrations did not last for long. The win was a controversial one. Analysts and critics believed that Wale Tinubu and his new team lacked the experience and wherewithal to effectively manage a corporation as huge as Unipetrol. It was completely unheard of in corporate Nigeria that a crop of young entrepreneurs, all aged under 35, could acquire such a huge company and have the funds and technical know-how to effectively manage it.

It caused uproar in several quarters and the BPE was under immense pressure to relinquish the sale. Because the BPE could not reverse its decision for legal reasons, it set new rules for the game, namely: Tinubu and his team had only two weeks to raise the $15million for the stake. If they couldn’t raise the money within the specified time, they stood to lose Unipetrol.

Tinubu was under withering pressure, but he moved swiftly. He raised $15 million within two weeks by obtaining a $10 million loan from a local bank, and selling equity in Unipetrol to a venture capital company for $5 million. On top of that he had $1 million in cash. Once again, Tinubu had defeated the odds. Apparently, employees at Unipetrol were less than impressed by the successful acquisition by Tinubu and his team. They couldn’t stand the idea of the company being led by three youthful individuals. Obstinately, they refused to work under this new leadership. The unions went on strike.

In their opinion, Tinubu and his team knew absolutely nothing about running a company and were only interested in running it into the ground. And so every morning, when Tinubu and his team turned up for work, they were greeted by placards brandished by their new staff. The placards branded them ‘eaglet managers’, in reference to their age which was about the same as that of the Nigerian junior team, ‘the super eaglets’. As Tinubu reminisces, he interjects: “You know, they still call us eaglets to this day.” It was a frustrating time for Tinubu.

The Unipetrol employees refused to accept Tinubu and his team as the new helmsmen; they refused to work. Ever the master strategist, Tinubu realized that he could never win without the support of the team, but at the same time, he knew he could not address the whole team at the same time. Tinubu identified the union leaders and the major movers, isolated them from the crowd and held talks.

Tinubu convinced the union leaders of his good intentions and also appealed to their self-interest. Hepromised the team that there would be no layoffs; employees who were due for promotion would be promoted; he promised a better welfare package for everyone. The uproar died down; there was still some skepticism in some quarters, but for the most part, the employees were ready to work again. Meanwhile, Tinubu set out to deliver committed… And after a while, frombeing the eaglets, we started beingreferred to as the old lions. From being the eaglets, we now became the bald eagles, because we were the ones with the wisdom, the strength and theconviction to do what was right and we always delivered all the time.” It’s been several years since Tinubu took over the company’s operations.

In 2002, he spearheaded another audacious acquisition. This time around, it was for Agip’s downstream operations in Nigeria. Unipetrol acquired 60% equity in Agip Nigeria PLC from Agip Petroli International. Unipetrol subsequently merged with Agip in 2003, and the new merged company was rebranded Oando PLC. With the merger, Oando emerged as the largest downstream company in Nigeria. Oando now has retail outlets in Benin, Ghana, Sierra Leone andTogo. Its growing regional expansion is in line with Tinubu’s grandiose ambition to build Africa’s first oil major. Tinubu has pursued some rather ambitious projects in rapid succession. Oando achieved a first in 2005 when it became the first Nigerian company to accomplish a cross-border inwardlisting on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange. Seeking to diversify his company’s operations from a mere fuels retailer to the realm of a major indigenous upstream player, in 2005 Oando incorporated Oando Energy services, an integrated oilfield services company.

Two years later, in 2007, the company acquired two oil drilling rigs for an estimated $100 million for use in the Niger Delta. In 2008, Oando acquired a 15% stake in two producing deep water assets–OML 125 and 135 located in Niger Delta. By 2009, Oando’s fleet of rigs had increased to five. Oando is also a major player in the midstream sector of the petroleum economy. In 2007, the company’s subsidiary, Gaslink Limited, completed the laying of a 100km gas distribution pipeline in Lagos state. Gaslink has successfully phased and executed the construction of about 100km of natural gas pipeline distribution network from the Nigerian Gas Company city gate in Ikeja, to cover the Greater Lagos Area including Ikeja, Apapa and their environs. Gaslink currently deliversover 40 million standard cubic feet of gas to over 100 industrial customersevery day. “Africa is a challenging continent; you fight for water, you fight for food, you fight for shelter. We compete by nature, so it’s always difficult but we don’t always know it is difficult because we have a spirit of survival. And that’s what we do–we survive. Here at Oando, we deliver on the tough things,” he says with a grin. Tough? Now we are back to the beginning and the leaky tanker with its mutinous crew

Loading...