The African Bank’s problems could have tied the best manager in the world in knots.

For three years the bank had been struggling to recover from the biggest ever foreign exchange scandal in South African history; most of the management were still in prison; it was short of money; the board was divided; on top of that the bank had gone through a massive recapitalization.

On a leather chair, in the middle of it all, sat the CEO, Gaby Magomola, who was about to go through the worst day of his life in business and suffer the prolonged pain of its aftermath.

Magomola was the man leading the turnaround, who had a past as complex as the problems of the bank. He was a high school drop-out, who spent six years as a convict on Robben Island, who had somehow transformed himself into a family man and Wall Street banker.

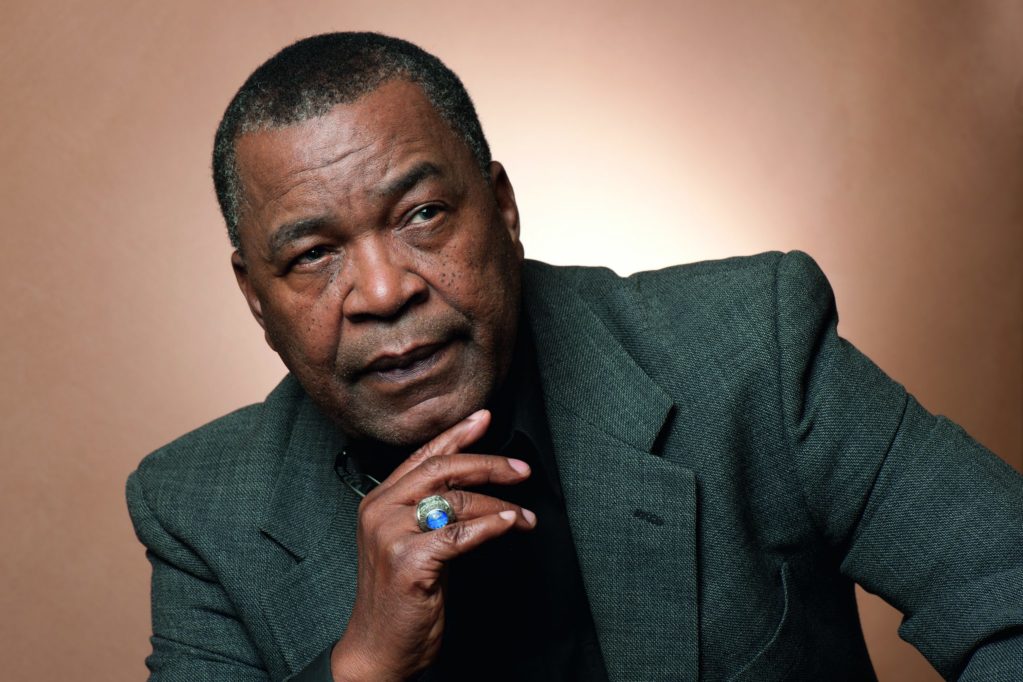

Gaby Magomola ponders on his worst day

In the depths of a cold winter, Magomola was feeling increasingly uneasy in his oak-paneled office and double-breasted suits.

The problem was the board and management of the African Bank were divided and the cracks were showing in the polished veneer of South Africa’s first and biggest wholly black-owned financial institution.

At this time, Magomola’s determination and desperation to hang onto the top job at the African Bank ran deeper than any desire for the social trappings. His vulnerability and pain stemmed from his passionate belief that the bank was more than just a money lender. To Magomola, the African Bank was a potent symbol of the economic emancipation of the oppressed: the people he had grown up with.

In many ways, Magomola embodied the dream. The Magomolas became the first black family to move into the affluent and lily white Wendywood suburb in Johannesburg in 1986, in firm defiance of the apartheid laws.

In fact, most events in Magomola’s 44-year existence had been the calculated moves of a man who believes he deserves more than circumstances offer.

He was born in a township near Johannesburg—an average African kid with an above average mind. His home was Bekkersdal, his mother was a casual worker in a nearby town and his dad a store clerk. Despite early academic promise, Magomola dropped out of high school one year before matric and submerged himself in the anti-apartheid struggle. This landed him on Robben Island in 1963 aged 19, where he spent years in the company of political leaders like former South African president Nelson Mandela.

Magomola completed matric in prison and later, a Bachelor of Commerce degree through long-distance learning university, UNISA. The dream was to qualify as a Chartered Accountant. The setback was merely the lack of segregated toilets in South Africa’s big accounting firms.

In 1976, Magomola, his wife, Nana, and children left for the United States. Magomola had won a Fulbright scholarship to study towards a Master’s degree in Business Administration at Ball State University in the American Midwest.

Magomola graduated and found work in Citibank in New York, where he says he “learnt the art of business and the beauty of living with people of different races”. The call of Africa became too loud to ignore in 1982 and Magomola transferred to Citibank’s Johannesburg branch. It closed shortly after President PW Botha’s now infamous Rubicon Speech—which quashed any hopes of political reform in the country.

In 1986, Magomola’s world was at his feet. A stint at First National Bank (FNB) was followed by an offer from the bank of his dreams. The African Bank was a lender under Reserve Bank watch, with almost no capital, big losses and no leadership on account of the majority of management residing in prison following the fraudulent forex dealing. Mildly put, it was a Herculean job.

Magomola pursued a private recapitalisation of the bank’s balance sheet and the target was African communities. The dream was economic grass-roots activism. “Political struggle was not enough. People had to own their own institutions,” he says.

It all boiled down to a conflict over strategy. The Magomola camp wanted the African Bank’s expansion to be a gradual process, a five-year plan around funding informal, small and medium enterprises in the burgeoning township economies.

The other, much more powerful camp held a vision of fast growth based on a model successful among the big boys like FNB.

“There was no realization of the complexity that the amount of business a bank can do depends on the capital it has,” says Magomola.

The job of a CEO, with a board divided, was not an easy one and the moment of truth for Magomola came just before lunch on a cold winter’s day by the hand of an old friend.

There had been a tense board meeting. Magomola was back in his office wondering what to do. All of a sudden, there was a knock on the door. On the threshold stood founder and chairman Dr Sam Motsuenyane—the very man who had enticed him to the African Bank from his cushy position at FNB just three years earlier. Magomola calls it a classic “et tu, Brute?”. Without saying a word, Motsuenyane handed over a letter demanding his resignation.

“I thought we had a warm relationship; he was not the kind of chairman that interfered in the day to day running of the business,” says Magomola.

Worse was to come. Letters from management said Magomola’s crimes ranged from favoritism to an attempt to bring American standards into an African business—taboo in the late 1980s, when African nationalism was on the crest of a wave.

In the depths of his worst day, Magomola staggered from disbelief to quiet desperation. He tried to rally his troops only to find they had all deserted him.

Magomola’s head was on the chopping block and he could do nothing about it—he was gone.

Grief followed denial and Magomola descended into a deep depression and alcohol. The banks repossessed the house in leafy Wendywood and the luxury car.

More than 20 years later, Magomola says that the real pain from his dismissal was rooted in the deep-seated belief that he was helping build a new economy.

“I received a lot of offers but none were attractive in the way I had aspired to make a difference when I was on Robben Island,” he says.

Redemption came a year later when the Foundation for African Business and Consumers Services approached Magomola to create another African lender and he became the pioneer of black economic empowerment. Now he helps his son, Thabo, run an investment holding company.

Looking back, what would you have done differently?

I may, in the circumstances, have breached the basics of the changed environment I was operating under. The concept of a corporate strategy and its implementation would have been better grasped at the level of my colleagues at the larger banks where I was trained and worked. However, operating under a board of directors who had not had a similar re-orientation such as the one I received through my exposure abroad, was in itself an obstacle. Walking too far ahead of those whom you lead can be counterproductive.

Loading...

Loading...