When former Ugandan president, Idi Amin, gave Asians a 90-day ultimatum to get out of the country in August 1972, he sparked a desperate fight for life for more than 60,000 people.

Some, who feared Amin’s brutality, had nowhere to run. Their bodies were found in the waters of the Nile.

Hitherto happy families fretted as they sought survival. Among them was a Ugandan Indian retailer’s family that took flight leaving behind, in the midst of panic and confusion, a 16-year-old son.

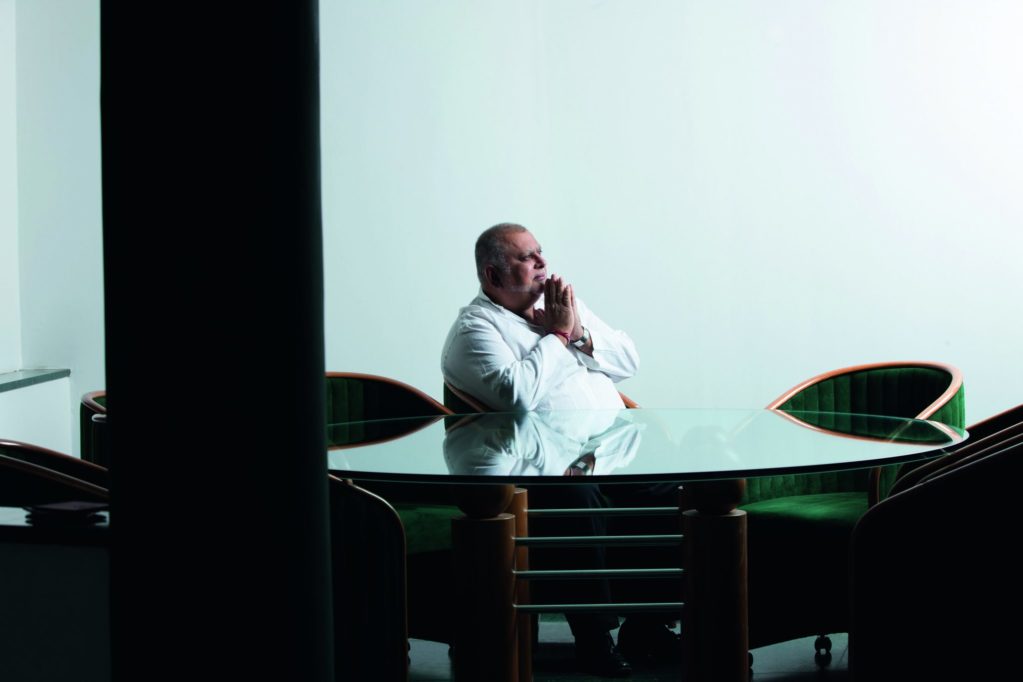

This vulnerable teenager was Sudhir Ruparelia.

More than 40 years on from this tearful parting, Sudhir is ranked by FORBES as the 24th wealthiest person in Africa with an estimated net worth of $1.1 billion. His is a remarkable story of hard work and endurance.

In an interview at his plush office chambers, in the heart of Kampala, Sudhir recalls how staying behind didn’t bother him when his family fled to Britain.

“It was an awful moment for the Asian community. You couldn’t predict what was to happen to you the next day. But I convinced my parents to leave me behind on the promise that I would join them later,” he says.

Sudhir’s Ugandan-born parents had established a shop and gas station in the middle of Queen Elizabeth National Park in western Uganda. They ran it for years.

The bravery and tenacity that that helped Sudhir survive and prosper amid chaos can be traced back to his childhood.

Sudhir studied in schools that were far away from the wildlife park where his parents ran their business. This meant he traveled long distances alone.

He cadged lifts on trucks ferrying traders. The trucks would leave the bush loaded with fish and salt and return packed with merchandise. Although the East African railway service was booming at that time, Sudhir says it was only for the rich.

At school, there was no communication with his parents until the holidays.

This forged a hard edge to Sudhir. All he wanted from his departing family was money to survive. His wish was granted.

For six weeks, Sudhir ran riot with his friends.

“We had a lot of money to party and drink. The security personnel occasionally stopped us but we always sweet-talked them into releasing us,” he says.

His moment of truth came when intelligence men arrested one of his friends. They wanted to extort money.

“Once he was released, we all decided to leave since the city was also getting desolate. There were just about 100 Asians left,” says Sudhir.

There was nothing left, but to flee.

Sudhir landed alone in London and didn’t even know where to find his parents. Together with other exiles, he was checked into a refugee camp. On the second day, he set out to find friends in Finchley Central. He found eight of them living in a two-roomed house. He never returned to the camp.

After five weeks in London, Sudhir found his family, but only to tell them that he wasn’t content with his refugee status and that he was moving on. He headed to Birmingham and Manchester where there were jobs that could promise permanency.

Sudhir tried to get work at Ford Motor Company but was thwarted by a union closed shop. He moved to Ilford, in northeast London, where he found a job with a company that made test tubes for laboratories. He handled red-hot wax in making centimeter markings on test tubes.

“This was the most sickening job in the entire factory. I barely had any protection and the heat was unbearable. No wonder I worked for only five months and moved back to Finchley Central,” says Sudhir.

Next, he tried to join the Royal Air Force (RAF). He passed the tests and was on the verge of signing for five years.

The problem was he was a minor and needed the consent of his parents. His mother declined. Her idea of the military had been tainted by the cruelty she had witnessed by the Ugandan army. Sudhir’s father differed but the mother held sway.

The RAF offered education. Sudhir hoped for academic success, but it was not to be.

Next, came a string of lowly jobs leading to a supermarket where he worked hard and bought a car. He used it as a cab at the weekends for extra cash. At the same time, he enrolled at a college for A-level studies, majoring in economics and accounts. He completed his studies and worked for a number of companies.

His wife, Jyotsna, with whom he worked at the supermarket, advised him to concentrate on one business. When they got married, Sudhir ventured into real estate in London. He bought properties, renovated them and sold for a profit.

Through this time, Sudhir had an uncle who had stayed behind in Uganda. He kept the link with home.

In February 1985, Sudhir returned to Uganda, aged 29, with $25,000 he earned through real estate deals in London. Due to unrest, Uganda was hit by foreign exchange shortages that caused the decline of the Ugandan shilling (Ush) to a low in 1985 of Ush600 to $1.

Sudhir says he kept a low profile for over a year to allow him time to study and understand the ruined economy.

In December 1986, Sudhir opened a wholesale store, in Kampala’s central business district, dealing in imported beer, salt and wine. The civil war left the breweries of Uganda in ruins.

This made it lucrative to import beer, with household goods, from Kenya. Sudhir positioned himself as a channel between importers and retailers. He became a trusted business partner to the importers, who supplied him the items on credit and claimed payments after a couple of days, to accelerate returns. He ran the system effectively and set up the first solid distribution structure in Kampala.

“While in London, the strongest trait I learnt was being disciplined. I ensured that the suppliers’ money was always readily available as agreed,” he says.

After just three months, he became the number one dealer in imported beer in Kampala.

Armed with a sound supply chain, Sudhir wasted no time in elevating himself to importer. This required piles of foreign exchange. So, he started a currency exchange service, which was another untapped market in Uganda.

Though the sector operated informally, the demand was overwhelming. Sudhir earned $10,000 in profit every day. He invested part of this money in prime properties in Kampala.

In 1990, the government moved in with a policy to regulate forex businesses, which had mushroomed. Sudhir’s Crane Forex bureau became the first to be licensed in the country. This catapulted him beyond his wildest dreams. In just six months, Sudhir says, he was making more money than the commercial banks.

He itched to grow his financial services empire and in 1995 created Crane Bank with $1 million.

Part of his frustration, was the way commercial banks operated as if they were doing everyone a favor. The charges were high and the choice limited. Sudhir’s came up with a motto for his new bank: Serving To Grow And Growing To Serve.

He lowered bank charges, extended banking hours; becoming the first to operate to 5PM and on Saturdays. He also cut red tape.

Today, Crane Bank is worth $120 million in capital and has 38 branches across the country. The country’s second largest commercial bank was voted Bank of the Year Uganda in 2009 and also won the Banker Of The Year award in 2003, 2005, 2006, 2007 and 2008 by the Financial Times in London—where Sudhir’s working life began.

In 2011, the bank posted a 32.3% increment in profit, before tax, rising to Ush90.23 billion ($37 million) from Ush68.19 billion ($28 million) in 2010.

“We are currently about 35 million people in Uganda. Only three and a half million live in Kampala. The rest of the population is in the countryside. That has guided our philosophy of opening more branches up country,” says Sudhir.

His plan is to open 10 branches a year for the next three to four years, with the hope of expanding into Rwanda in March this year, followed by South Sudan.

In his office, Sudhir’s wide collection of awards is impressive. He has won almost of the top investment awards in Uganda, including the Presidential Export Award for 2002, 2006, 2005 and 2009. He also received an honorary Doctorate of Law in Business from the Uganda Pentecostal University for his investments in the Ugandan economy.

A family man, with two daughters and a son, Sudhir’s investments are run under the umbrella of Ruparelia Group of Companies, which also holds high value assets in the property development and management, insurance, education, media and hotel sectors.

Through his floriculture company, Rosebud Ltd, Sudhir has been exporting 13 million roses to Europe a month earning him a profit of $5 million per year. Production is set to increase once he acquires a planned 200 additional hectares. He will effectively produce one and a half million stems a day, creating 7,000 jobs and projected returns worth $95 to 100 million per year.

It hasn’t been all rosy at Uganda’s largest flower exporting farm though. The firm was cited in alleged environmental degradation. The National Association of Professional Environmentalists have accused Rosebud of polluting the Lutembe wetland, on the shores of Lake Victoria, with pesticide and fertilizer effluents, according to FORBES.

However, the National Environment Management Authority, a semi-autonomous institution and principal agency in Uganda charged with the responsibility of coordinating, monitoring, regulating and supervising environmental management in the country, says it has found no fault with Rosebud.

“We licensed Rosebud in 2004 with well stipulated guidelines to follow in safeguarding the environment. We have been monitoring their operations and have no queries save for the wrong perception of some members of the public,” says the authority’s executive director, Tom Okia Okurut.

Sudhir, who is hesitant to delve deeper into the matter because it is before a court, says his plans have the blessing of the environmental regulator.

Last year, residents tried to block the road leading to the farm in protesting the expansion plans. Through his lawyers, Sudhir sought a court injunction to have the development continue.

The Ugandan parliamentary committee on natural resources also instituted investigations into the matter but the speaker halted the proceedings citing sub judice. The real estate business is simpler.

Through his estate holding company, Meera Investments—named after his first daughter—Sudhir owns at least 300 residential and commercial properties in Uganda, from Crane Chambers in the central business district, to scores of apartment blocks, shopping centers, office buildings and tracts of valuable land. He estimates his rent is around $600 million a year from his real estate.

His five-star Speke Resort and Conference Centre, situated on 75 acres, by the shores of Lake Victoria near Kampala, played host to the 2007 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, which drew 59 leaders. Built for the Commonwealth meeting, the resort has 780 rooms, 10 conference rooms, a 1,000-seat ballroom and nine meeting rooms that can accommodate groups ranging from 10 to 300 people. It also has Uganda’s only Olympic size swimming pool, an equestrian center and a host of bars and restaurants.

The plush hotel, worth around $165 million, caught the eye of the late Libyan president, Muammar Gaddafi, who tried to buy it for $120 million. Sudhir turned him down.

His other assets include Speke Hotel, Kabira Country Club and Speke apartments, all high-end facilities in prime zones of Kampala and worth millions of dollars.

Sudhir also bought Victoria University from Edulink Holdings Ltd to add to his educational institutions portfolio already comprising of Kampala International School Uganda (KISU) and Kampala Parents’ School. The institutions are worth more than $40 million.

Asked what guides his investment, Sudhir says it is instinctive risk taking rather than feasibility studies.

“In Africa, feasibility studies are a waste of time. It’s about ability to see opportunity and take it up. If you did feasibility studies for a country like Uganda, you would never do anything,” he says.

Sudhir, the man who drove a cab for pennies and turned down Gaddafi, can never be accused of shrinking from a challenge.