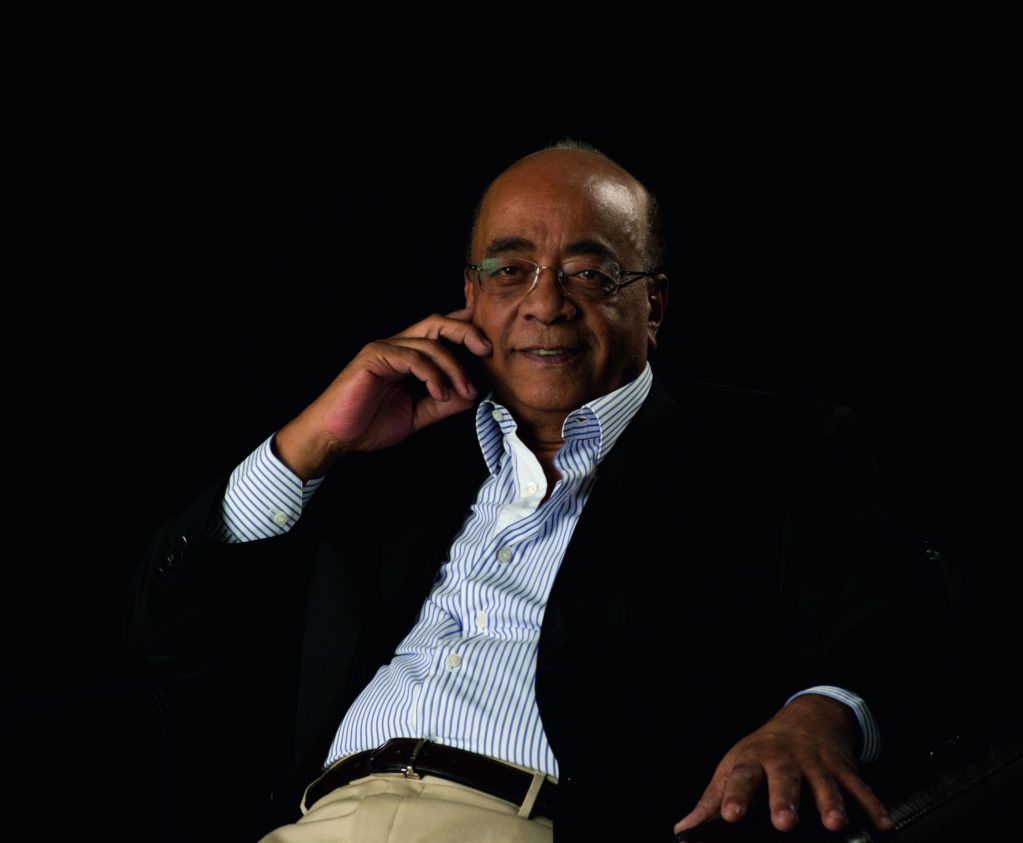

Mo Ibrahim is rich, relaxed and a lot of fun. He sees humor in the leadership of Africa as he delivers his Nelson Mandela lecture. He compares Robert Mugabe to Bill Clinton and Barack Obama who both ran the world’s biggest economy in their 40s.

“Here we have somebody in our neighboring country, who, at 90 years old, is about to start a new term. So what is wrong with us? And the other day I was thinking, ‘If Obama senior decided to take the young Obama back to Kenya, where would the young Obama be today?’ You may guess, I know, he will never be president of Kenya,” says Ibrahim to laughter from the audience in Pretoria.

Ibrahim knows Africa like the back of his hand. He was born in Sudan in 1946, the second child in a family of five. He went to school and university in Alexandria, Egypt, where his father worked as a cotton trader. After university, Ibrahim went to work for the telecommunications department in Sudan. Following training and assignments abroad, he completed his Masters and Doctorate at the University of Birmingham, in England.

It led to an opportunity to get in on the ground floor of world telecommunications. Ibrahim joined British Telecom (BT) as a technical director when it won the first license for cellular technology. He designed the first mobile network in the United Kingdom.

Ibrahim left BT to start Mobile Systems International (MSI) and founded Celtel International, one of the first mobile phone networks in Africa, in 1998. At the time, people were scrambling for licenses everywhere but Africa. The general consensus was that Africa was too difficult.

Loading...

“Wherever there is a gap between perception and reality, there’s a good business opportunity,” says Ibrahim.

He sold MSI in 2000. Celtel was sold in 2005 to MTC Kuwait for $3.4 billion, making him a reported $1.4 billion. At the time, the company had six million subscribers in 13 countries.

Ibrahim hails mobile technology as an African success story, but cautions that despite the continent having more mobile phones than Europe and the United States, it makes none of them. He says African nations should sign contracts with mobile companies forcing them to set up factories here and then transfer the skills.

The leadership that could bring this about has been honored with millions of dollars by the Ibrahim Foundation, launched in October 2006, to support good governance and great leadership in Africa. The foundation publishes an annual index on the quality of governance.

The Ibrahim Prize—of $5 million-a-year for 10 years—has been awarded a mere three times and goes only to former heads of state. In 2007, it went to former president of Mozambique Joachim Chissano; in 2008, Festus Mogae of Botswana; in 2011, Pedro Pires of Cape Verde.

Ibrahim says that it’s a prize for excellence that doesn’t come easy. He adds it is a prize and not a pension. Many do not agree with the idea, but Ibrahim challenges people to name three western leaders who could have won it in the last six years.

On the business front, Ibrahim is trying to channel investment through Satya Capital, of which he is chairman.

“Business is wonderful because business means prosperity, development and jobs,” says Ibrahim.

Good business that is. Ibrahim is disturbed by fellow African businessmen whom he believes are detached from society. A closer interaction is essential because, he says, business cannot succeed if society doesn’t thrive. He also thinks that the business world is too scared to rock the boat and hold government to account, forcing transparency and good governance.

Ibrahim is a proponent of integration. He feels that achieving a central market for Africa is essential, that the continent has yet to achieve this because of a lack of political will. According to Ibrahim, an African business plan must begin with integration and that Africa needs scale that allows the development of industries to compete with India, China, Brazil, the European Union and the United States.

“We cannot really build 54 successful small economies in Africa, it’s out of the question,” says Ibrahim.

“Only 11% of our trade is amongst Africans. We refuse to let our people travel from one country to another.”

Ibrahim says Africa needs infrastructure, roads and railways, power generation and broadband.

“Africa will not develop just by accident, people need to work and see what needs to be done and work together,” he says.

Then, there is youthunemployment.

“If you are a young African person, the more educated you are the more likely you are not to get a job. Our education system is not providing the skills for the job market. We need to rethink how our schools teach,” says Ibrahim in a speech to the Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC), an organ of the United Nations.

“The future is theirs [the youth], they have a better understanding of the future than us. This continent belongs to its young people,” says Ibrahim.

Delivering the 11th Nelson Mandela Annual Lecture, Ibrahim posed a question whether young Africa can become the factory of the world when China has no youngsters to work in theirs, in 10 to 20 years time, because of the aging population.

What about the notion that China is taking over Africa? Ibrahim sees this as a healthy business relationship as long there is technological transfer, local sourcing of components, transparency, and respect for the environment and communities.

“Why are Africans poor when we have a rich continent?”

More money is lost from multinationals not paying tax, through what he calls ‘fancy accounting’, than gained from aid. He calls for a strengthening of tax institutions. Although the west has woken up to tax dodging, Africa slumbers.

Governance, according to Ibrahim, is about making difficult decisions and being judged on the numbers.

“Physics and numbers don’t lie, but people do,” he says.

Ibrahim says there is a dearth of leadership in Africa; that leadership is not about bossing people around, having a seat on the Security Council, or chairing the AU. It’s about engaging with others.

He says that the continent holds South Africa up as a role model, but that the country has become too arrogant and refuses to learn from other countries.

When the BEE policy was introduced in South Africa, Ibrahim asked his friends in the ruling party if this was not a slippery slope to corruption. He says that the policy has done nothing to keep South Africa from being at the bottom of the Gini Index scorecard, making it the most inequitable country in the world. He says there should be no “sacred cows”, including land reform. If something doesn’t work then policy makers should revisit it.

The 2013 Ibrahim Forum will be held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, in November and will discuss where the continent is going after 50 years of the African Union. It will focus on achievements and those that got away.

Ibrahim doesn’t know where he gets his sense of purpose from, but he simply sees things that need to be done and does them. In the end, Ibrahim just wants to be remembered as a son of Africa that made it in the west and never forgot his people.

Loading...