Chid Liberty is not your typical businessman, particularly not the kind you would expect to find in Liberia, a nation where big business has always been dominated by a cast of outsiders: middle-aged Lebanese men renting out overpriced apartments and selling American imports in slick grocery stores catering to high-maintenance humanitarian workers, Indians trading in electronics, rice and pharmaceuticals, and multinational companies exploring and exploiting the sea and land for oil and minerals. Nor is Liberty your usual “been to” young Liberian who has returned with a degree from a US university to take up a high-level position within a government ministry. Liberty, born in Liberia and raised in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, after his family was forced into exile in the 1980s during the military rule of the then president, Samuel Kanyon Doe, came back to his homeland with a grand ambition: to sow the seeds of an industrial revolution in a nation whose economy has been dependent on natural resource concessions and foreign imports throughout its history.

In 2009, Liberty and his business partner and best friend from Milwaukee, Adam Butlein, set up Liberty & Justice, the umbrella company that founded the Liberian Women’s Sewing Project (LWSP), the first certified fair trade factory in Africa and the first garment factory in Liberia.

“One of the core reasons we started our company is because we thought that what every developed economy has done so well is started really large industries that employ masses of people with low skills and education,” Liberty says.

Liberty and his partner focused on developing a project for women, as numerous development studies they read pointed to the important role that women’s employment can play in poverty alleviation within communities. In contrast to NGOs that train women to make handicrafts and tie-dye, Liberty combined a commitment to social justice with a shrewd business sense and approached large buyers from the United States.

Loading...

But starting up a business in a non-existent industry in Liberia wasn’t easy. When Liberty began searching for funding for the project, he was often met with a harsh response.

“You talk to your first two or three people and you say, ‘Hey I am trying to put a couple of hundred thousand dollars or a couple of million dollars to build a factory in Liberia’, and they say, ‘Are you crazy?’ which is a response I got quite often,” says Liberty, a dapper man who punctuates his sentences with expletives.

Liberty and his partner started the business with a paltry amount of personal savings and raised an initial round of $600,000 partially from friends and family, but mostly from angel investors. The business that started with 30 women making T-shirts in a factory in Sinkor, Monrovia now employs 250 women, 100 in Liberia and the rest in a recently-constructed factory in Tema, Ghana. With customers like Godiva chocolate, the US-based apparel companies Haggar and prAna, and the Japanese company Itochu Corporation, Liberty says he expects the business to generate $40 million in revenue over the next year. He says he will need around 2,500 workers to fulfill his current demand and is looking at the possibility of expanding to other countries in West Africa.

Vamoma house is an odd retro geometrical cream and white building off Monrovia’s main thoroughfare, Tubman Boulevard. Like many of Monrovia’s large structures it was a battlefront during the war and was left looted, pierced with bullet holes and used as a mass gravesite. The presence of the factory on the first floor is testament to the progress Liberia has made since the end of the civil war in 2003.

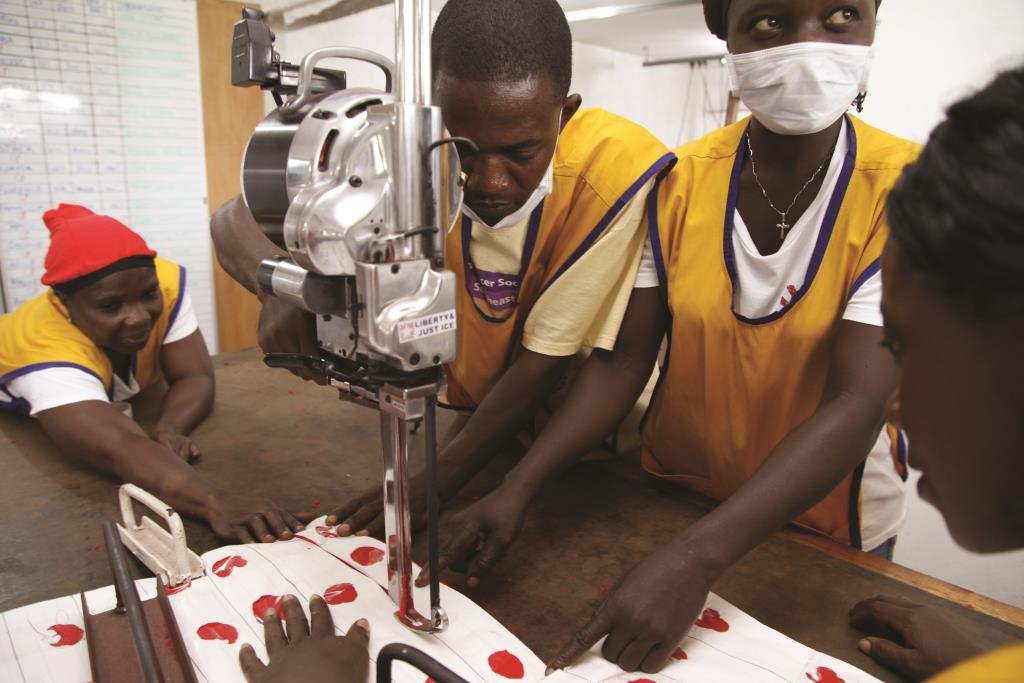

Inside, women are busily cutting red cloth and stitching together a batch of T-shirts for an order. Along the two production lines, the women sit dressed in yellow aprons and black hairnets beneath fluorescent lamps and look intently at the pieces of red cloth they run rhythmically through the machines. A short, middle-aged Filipino woman named Loderena Rojas, who has spent the past 30 years working in the garment manufacturing industry in her homeland, stands at the front quietly watching over the workers. Liberty’s factory looks like one you’d expect to find anywhere in the world, only smaller. They will be moving into larger premises—an old Volkswagen distribution showroom—in the bustling downtown commercial district of Waterside in the coming months.

The women earn $100 a month, a modest wage, but well above the average annual income per capita that rests at $400 a year, in a country with an unemployment level at almost 80%. But the workers also receive $30 a month for transportation and a bag of rice, along with healthcare and an annual savings matching program that rewards them dollar for dollar with what they manage to save in their bank accounts. The women of LWSP hold a 49% stake in the factory, which is all part of Liberty’s business approach. For Liberty, worker ownership plays an important role in creating a productive workforce, particularly in the Liberian context, where it’s mostly outsiders and the elite who have benefited from successful businesses.

“Worker ownership and partnership with the Liberians, having them own a piece of company really changes the conversation. There is a ‘boss man culture’ here because it has been a chief-based society—you won’t get rid of that—but in terms of getting workers to take responsibility, if people feel that they are a partner in the company, it changes the paradigm. We have gotten timeliness and productivity out of workers that are unheard of, and we haven’t gotten it out of fear, which is the tactic they use in Asia.”

Fifty-two-year-old Leona Monger, a petite woman wearing fine gold-rimmed spectacles and a red headscarf who lives in a slum known as Vai Town, is head of the workers’ union and has held her position at the factory since it was established. While Monger says there is room for improvement in the pay, she says her wage has allowed her to keep her three children in school and set up a small provisions store.

“I see a future, not only for me, but for the younger ones who have just started. There are a lot of incentives that will enable us workers to improve our lives,” Monger says.

Unlike economies of developing countries throughout Asia that have been buoyed by investment in the manufacturing sector, Africa is still viewed by many foreign investors as a continent whose only value exists in natural resources. A survey released by Ernst & Young earlier this year focusing on Africa’s perceived “attractiveness” to investors found that despite the fact that foreign direct investment grew by 27% between 2010 and 2011, there “remain lingering negative perceptions about the continent”, namely that Africa is unstable, corrupt and a risky region for investors, but these perceptions were held mostly by those who are yet to do business on the continent. For Liberty, the lack of investment in the manufacturing sector is due to misconceptions about the capabilities of African workers.

“I think the number one thing keeping the multinationals away from labor intensive industries in Africa is a complete mistrust of African human resources and African human capital,” Liberty says, adding this perception is often underpinned by racist stereotyping. “People say African workers’ hands are too big, they are too lazy, or they don’t respect time. I don’t think that can be true—if you can walk six hours to fetch water in the heat, laziness isn’t the issue.”

Under the leadership of President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, who was re-elected for a second term in November, the government claims to have attracted $19 billion worth of investment, mainly in the form of oil, mineral and agricultural concessions. But Sirleaf and many in the government and the business community say more needs to be done to ensure sustainable and equitable economic growth that will create jobs for Liberians.

“No country is going to get growth if you don’t have it [the economy] driven by exports or some kind of manufacturing,” says Monie Captan, president of the Liberia Chamber of Commerce. “We have to identify specific sectors, plan properly, and invest in these sectors. It is not going to happen by saying it.”

For Liberty, Liberia must move beyond its economic concessions for the sake of its future security and survival.

“There are also issues of political instability. As long as you are not employing people and are only giving jobs to a few lucky well-paid people, others will feel like they are getting nothing,” he says.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) in a recent policy paper expressed concerns about youth unemployment. The death toll of Liberia’s civil war made it one of the youngest nations in the world with 70% of the population below the age of 30. The IMF says that with 50,000 youths joining the labor force every year, the 90,000 jobs that the National Investment Commission estimates will be created from concession agreements over the next 10 years will do little to address the problem.

Liberia also faces major infrastructural challenges that make investment in manufacturing a challenge, among them poor road conditions and expensive and limited access to electricity—a consequence of the destruction of the Mount Coffee Hydropower Plant, for which the government only recently received funding from international donors to restore.

While Liberty acknowledges his factory is a small step towards Liberia’s industrial revolution, he is optimistic the nation can change the fabric of its economy through carefully developed government policy, investment in infrastructure and more open-minded foreign and domestic investment.

“I am positive that it will happen and at the end of the day the economics need to make sense. Currently, it doesn’t make sense, from a purely capitalist perspective… but we have labor at competitive rates, and with the infrastructure we should be able to compete with countries like Bangladesh and Cambodia and we should be able to get there in five to seven years if we are aggressive,” says Liberty.

Loading...