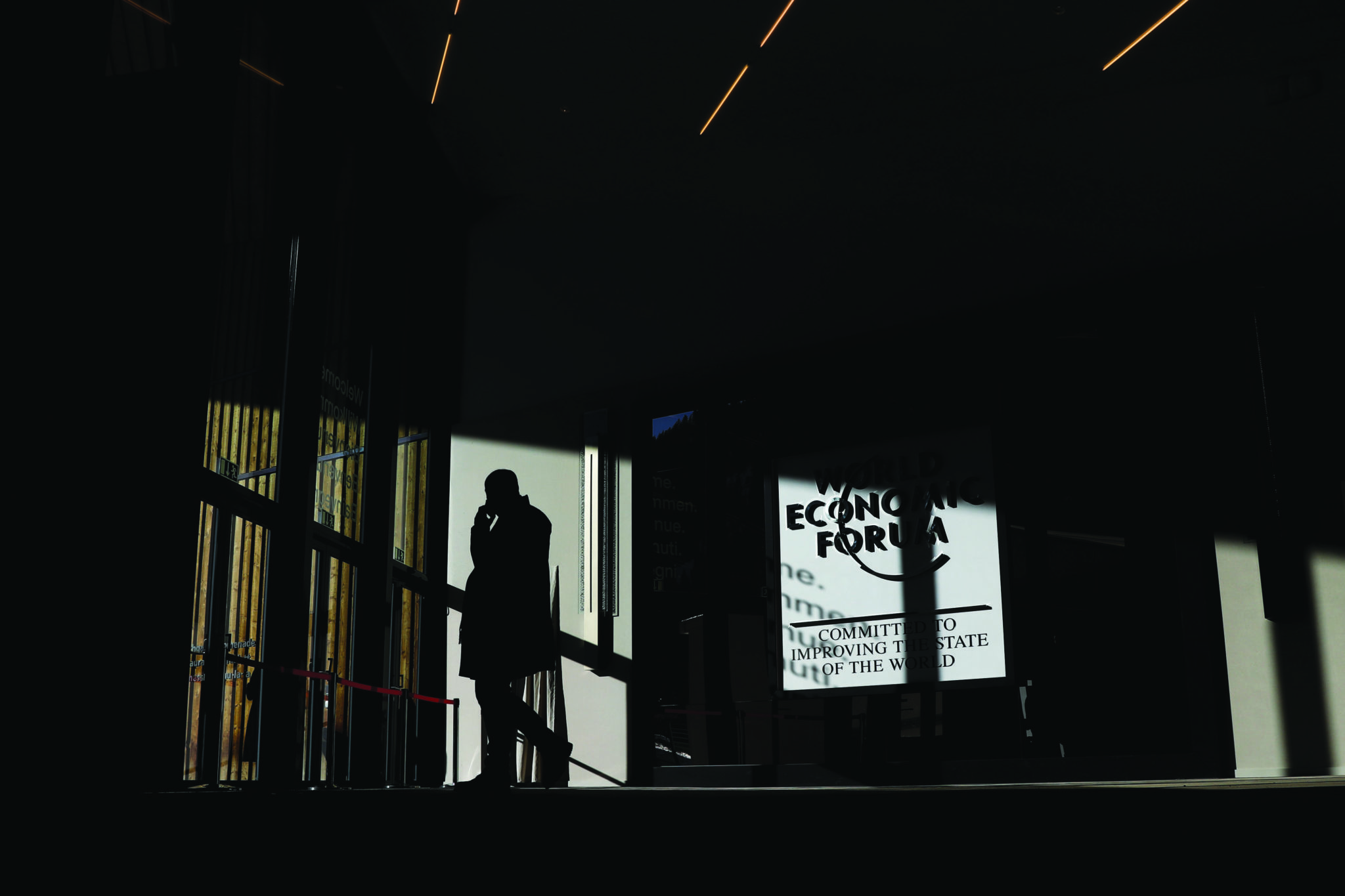

The multimillion-dollar circus called Davos rolled into the Swiss ski-resort yet again, in January, in all its big deal bombast and bean counting glory. This year, African debate was scant: the man who broke the Bank of England foretold of a broken world laden with fear and doom; there was scary talk of cyber terrorism; just another day, another Davos, for the World Economic Forum.

If you want an example of how the dash of Davos can descend into self-parody, you should have taken a look at the huge banner draped across the posh Belvedere Hotel throughout the World Economic Forum in the mountain ski-resort.

It was on the main street through Davos where thousands of delegates slip and slide to scores of functions – with at least one or two slipping over every day – along a line of shops taken over by big money corporate sponsors.

Much more money is being made elsewhere in this ski-resort: the people who live here go away for the week and let out their homes for a king’s ransom; $30,000 for the week is nothing unusual.

Loading...

Most people saw an irony in the banner, yet clearly the people who spent a fortune on putting it up there couldn’t have.

“Free trade is great,” says the banner on behalf of Brexit-bound Great Britain.

“Didn’t someone tell them they were about to leave one of the greatest free trade zones in the world?” says one passer-by with a cynical chuckle.

The crack summed up some of the irony that swirls around when cohorts of bean counters, highly-paid administrators and bosses gather in an Alpine icebox to solve the problems of the world.

The bigwigs weren’t there and this year, there was less buzz and fewer queues outside the briefing rooms.

Donald Trump, who made a big splash at Davos last year, stayed at home trying to figure out his government shutdown. The four ‘Ms’ – May, Modi, Macron and Mnangagwa weren’t there either; at least two of them tied up with fighting fires, from Brexit to economic meltdown, in their own backyards.

Empty hot seats, at Davos, at a time when the world is crying out for the wisdom of sage leaders.

Instead, it was left to business leaders, like the Australian-born CEO of billion-dollar turnover infrastructure giant Arup, Greg Hodkinson, to cut to the chase.

“We need clear political leadership in this fractured world… otherwise we are going to get easy political leadership preying on people’s fears,” says Hodkinson at one of the first panels of WEF 2019, on infrastructure.

READ MORE | Why The Richest And Most Powerful Go To Davos

Hodkinson, who has worked in infrastructure for 40 years, also said investment in infrastructure could no longer ignore the future, or the deteriorating environment.

“Carbon should be priced into infrastructure projects and that will act as an economic trigger for private money to come in because not only will it mean more revenue, it will help us put more money into saving the environment,” says Hodkinson.

According to the WEF Global Risks Report for 2018, some of the top risks by impact are posed by the elements: floods and storms; water crisis, plus earthquakes, tsunamis, volcanos and electric storms.

“By 2040, the investment gap in global infrastructure is forecast to reach $18 trillion against a projected requirement of $97 trillion. Against this backdrop, we strongly recommend that businesses develop a climate resilience adaptation strategy and act on it now,” warns Alison Martin, Group Chief Risk Officer, Zurich Insurance Group, in the report.

The money is there, according to Hodkinson, but needs to be channeled with foresight.

“Even if someone is building a car parking garage, I ask what else can they do with it because they won’t need it one day,” says Hodkinson.

“The money is there. Investors sank six trillion dollars into United States junk bonds last year; if investors are prepared to roll the dice on junk bonds, what about infrastructure investment?”

Investors, on this day at Davos, heard that 65% of world infrastructure projects are unbankable without government guarantees. Private money is needed to fill the gaping infrastructure gap, yet negotiations between investor and government officials can prove difficult.

READ MORE | World Bank Sees Global Growth Slowing In 2019

Just ask Heng Swee Keat, the Cambridge-educated finance minister of Singapore, the former Parliamentary Private Secretary to the father of infrastructure on the industrious little island who harnessed private money for public good – the legendary late premier Lee Kuan Yew.

The finance minister warned relationships between public and private sectors could be “lumpy”.

“I remember a man coming to me and saying he was never going to invest in infrastructure in your country again, I asked him ‘why’ and he said, because the last time we invested and made money the government came back to us and asked ‘why are you making so much money’,’’ chuckled Swee Keat.

Another major issue in Davos was Artificial Intelligence. This promises not only the development of new technology to take the backbreak and tedium out of life, but also to replace workers with robots. Exciting times for many, yet maybe worrying times for us all if one of the many briefings was anything to go by – one man’s bank account can be another radical’s cash cow. Experts painted a bleak picture of threats and radicalism lurking on the dark web.

“I wouldn’t put my credit card into a machine today. This is happening right now,” exclaimed retired US Marine Corps’ four-star general, John Allen, a former commander of NATO’s International Security Assistance Force. I had asked him about how far away we were from cyber-terrorism cleaning out bank accounts.

“A cyber terrorist can open a bank account on a Monday, start cleaning people’s accounts out on a Tuesday and start supplying money to their cause on a Wednesday. I saw a case of a bank in Bangladesh that was cleaned out of $80 million in one day. We have to develop strong systems to defend our financial systems.”

READ MORE | Big Four Accounting Firm Deloitte Confirms Cyber Attack

Cyber- terrorists are becoming ever more clever and ubiquitous, warns Karin von Hippel, a former senior advisor to the US Department of State, who worked on security for the United Nations and European Union in Somalia and Kosovo. The Islamic Isis movement, in Syria, attracted 40,000 volunteers from 120 countries and many used internet to further their cause, she says.

“They are all out there in the cloud and the dark web doing their work. They move so fast that it is very hard to keep up with,” says Von Hippel.

“If we spent half as much money on easing the causes of this terrorism, as we do fighting it, we would not drive so many youths into the arms of the radicals,” says Allen.

Don’t panic, too much, cautions Von Hippel.

“Despite all of this, you’ve still got a bigger chance of dying in the bathtub than you do in a terrorist attack,” she quips to ease the tension at the end of a worrying, yet eye-opening, session.

If you listened to South African President Cyril Ramaphosa at Davos, on a cold Wednesday night, you would have bathed with abandon and slept soundly in the snow afterwards.

“We are casting our nets here and finding big fish,” says Ramaphosa, the master of the metaphor, at the press briefing earlier in the day.

In Davos, Ramaphosa would have faced awkward questions from investors over why his government is propping up loss-making state enterprises, taking time to cut back government expenditure and the civil service, plus the thorny issue of expropriation of land without compensation.

That night, at the customary presidential dinner, in Davos, Ramaphosa, with microphone in hand, was as optimistic as a leader should be in an election year.

“When we see people here, they ask us how we manage to get business, government and unions working together for the economy of our country,” says Ramaphosa.

“They say tell us what magic you have. What I tell them is that there is a renewal and determination to make South Africa work. ”

The most chilling view of the future was yet to come. It came from the lips of grey-haired global investor George Soros, the man who broke the Bank of England, who invited us to the plush Seehof Hotel, one icy Thursday night, for an icier speech.

The 88-year-old hedge fund tycoon, worth $8.3 billion according to FORBES, reportedly made $1 billion in one day, in Britain’s sterling crisis of 1992, by shorting the British pound.

“I want to use my time tonight to warn the world about an unprecedented danger that’s threatening the very survival of open societies,” were the dramatic opening words.

Soros delivered a potted history of his early life in the shadow of oppression. When he was 13, in 1944, the Nazis invaded Hungary and deported Jews to concentration camps. His father, a lawyer, understood the system and arranged false papers and hiding places for the family.

When the Soviets moved into post-war Bucharest, Soros took refuge in England where he put himself through the London School of Economics by working as a waiter and railway porter. He became a leading hedge fund manager by analysing the weaknesses of prevailing theories guiding investors.

“Running a hedge fund was very stressful. When I had made more money than I needed for myself or my family, I underwent a kind of midlife crisis. Why should I kill myself to make more money?” he says.

Then, Soros began his philanthropic work, in 1979, by supporting scholarships for black students at Cape Town University. To this day, his Open Society Foundations aims to protect the human rights and freedom he fears are under attack.

“An alliance is emerging between authoritarian states and the large data-rich IT monopolies that bring together nascent systems of corporate surveillance with an already developing system of state-sponsored surveillance. This may well result in a web of totalitarian control the likes of which not even George Orwell could have imagined. Tonight, I want to call attention to the mortal danger facing open societies from the instruments of control that machine-learning and artificial intelligence can put in the hands of repressive regimes,” says Soros.

“China isn’t the only authoritarian regime in the world, but it’s undoubtedly the wealthiest, strongest and most developed in machine learning and Artificial Intelligence. This makes Xi Jinping the most dangerous opponent of those who believe in the concept of open society. But Xi isn’t alone. Authoritarian regimes are proliferating all over the world and if they succeed, they will become totalitarian.”

Soros also criticized US foreign policy on China. “My present view is that instead of waging a trade war with practically the whole world, the US should focus on China. Instead of letting ZTE and Huawei off lightly, it needs to crack down on them.

If these companies came to dominate the 5G market, they would present an unacceptable security risk for the rest of the world. Regrettably, President Trump seems to be following a different course: make concessions to China and declare victory while renewing his attacks on US allies. This is liable to undermine the US policy objective of curbing China’s abuses and excesses.”

The final chilling words for anyone who loves freedom: “My key point is that the combination of repressive regimes with IT monopolies endows those regimes with a built-in advantage over open societies. The instruments of control are useful tools in the hands of authoritarian regimes, but they pose a mortal threat to open societies.”

Journalists at least closed a heavy night with a lighter moment. They asked Soros whose side Facebook and Google were on.

“I think Facebook and the others are on the side of their own profits,” says Soros to a gale of laughter.

All the time we were listening to these predictions of AI surveillance doom at Davos, in a warm lounge at the Seehof Hotel, we were surrounded by armed police, airport security, surveillance cameras and cell phones that tell the world where you are, who you are and what you are doing, or saying, maybe doomsday is already here.

Loading...