To say Nicky Oppenheimer is understated is an understatement in itself. It is tantamount to saying his family – the third richest in Africa – is well off; or that Winston Churchill, another famous Old Harrovian, was a fair public speaker.

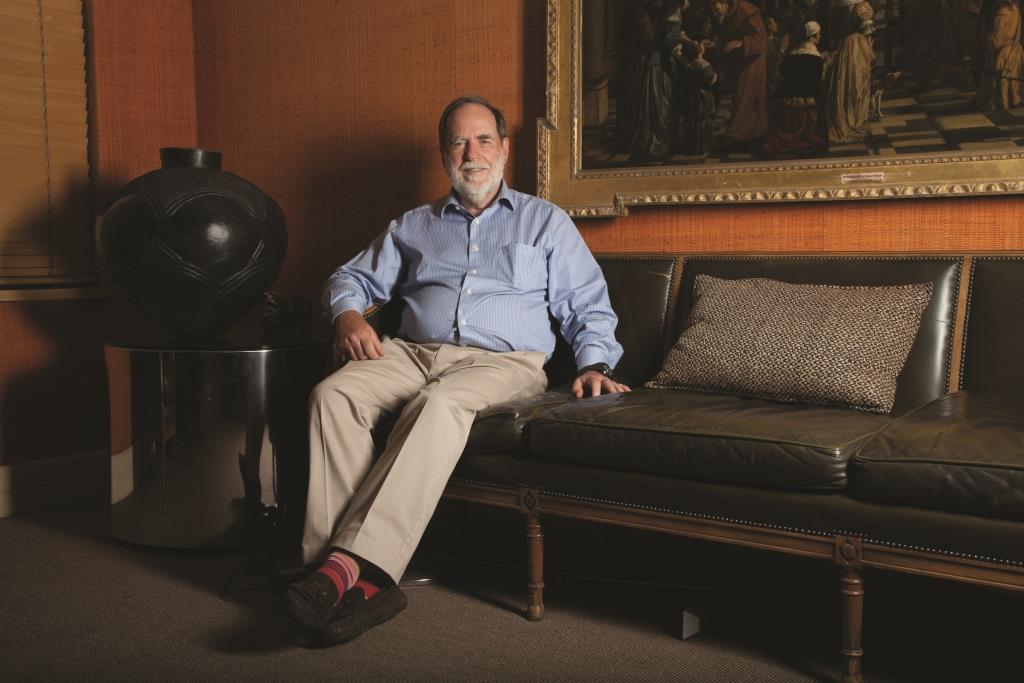

It must be tough suffering the stare and glare that goes with being the scion of a powerful world famous family, but Oppenheimer wears his eminence lightly as he sits opposite me for this rare interview. This Johannesburg office may be dressed lavishly, but the man himself, in a blue open-necked shirt, is not. He is measured, calm and guarded as he chats about everything from entrepreneurs and corruption to government and business. There is a glint of pride in the eye when he mentions, fleetingly at the end of the interview, his son’s first class cricket career as an Oxford Blue. Jonathan Oppenheimer bowled for Combined Universities against one of the world’s finest batsmen, West Indian Brian Lara.

“He bowled the first three and moved them away and then brought one back into the pad. Lara LBW Oppenheimer 0,” chuckles the proud father.

The laidback calm belies a busy few years for the Oppenheimers and the two corporate giants that the family took generations to build: Anglo American and De Beers. In the next few years, the family will invest billions into Africa and her entrepreneurs with straightforward business philosophy.

Loading...

“You have to learn to get on with people, you have to learn to determine the bullshit from the serious stuff, and then you have to have a good common sense and a vision of where you want to get to,” says Oppenheimer.

This no nonsense approach is driving the family forward in the business of private equity. The investment drive came after the wrench of selling out from De Beers, the largest diamond producer in the world. Along with Anglo American, De Beers may have survived political upheaval and two world wars, but the recession of 2008 proved a turning point.

“From a De Beers perspective, it came at a bad time. De Beers had just being opening new mines so we had to borrow money to pay for the mines – you don’t get a return very quickly – so we had to renegotiate our debt conversance with the bank, that environment wasn’t easy. We managed, we had to turn to our shareholders and get more money from them; this was post privatization. So both Anglo and the family put up more money, which was brave on both our parts,” says Oppenheimer.

“In my father’s lifetime, he talked about the great depression, where the situation was far more dramatic than anything I ever had to face, and you knew that people wanted to have diamonds, there was never any lessening of desire just that they didn’t have the income to do it. So you had to cut your cloth to suit that and wait for the times to improve… It never occurred to me that the business wouldn’t recover, there were times where you have somewhat sleepless nights.”

The emotional decision came in 2011. After 85 years, the Oppenheimers voted to sell their 40% stake in De Beers, the business that built the family fortune, for an estimated $5.1 billion. For the first time in decades, the family had no stake in any listed company.

“Not quite a difficult decision, the fact that there were three shareholders in De Beers, the family, Anglo and the Botswana Government was always in my view an unstable arrangement and I knew something was going to happen at some stage. Either Anglo would say it was not a business for them or they would say they really want to be in it in a much more serious way than we are at the moment and they came out on that side and made us a very fair and reasonable offer. And then of course I was in a difficult position because I had to deal with a business I had been in all my life on the one hand, and then the requirements of the family, my sister, her children, my children. We ended up in a situation where my heart made me say ‘look we should stay with De Beers’ but my head knew absolutely clear that this was the right deal to do.”

Analysts in Johannesburg will say Mary Slack, Oppenheimer’s sister, was a strong voice in the decision to sell.

“She (my sister) was not in the day to day running of the business… We all ended up wanting to sell,” replies Oppenheimer.

The parting broke a link with De Beers that dates back to Nicky’s grandfather, who led the family’s charge into Africa.

A London trading company posted 21-year-old EO Oppenheimer, the son of a German cigar merchant, to South Africa to buy diamonds. He took to the diamond trade like a duck to water and his knowledge of the stones was unparalleled; legend has it that Oppenheimer used to carry a note book around him to write down any useful business information. By the time he was 30, Oppenheimer was the mayor of the diamond town of Kimberly – no mean feat in an age when grey hair ruled the roost.

“I always remember him as a very quiet guy, I remember him as the sort of guy that if you bumped into him you rebounded,” says Oppenheimer.

The formidable Harry Oppenheimer was the next generation – a strident man who made his mark both in business and politics, as well as guiding his son in the art of business.

“No, I don’t think he was a tough man in business, he had a very good view of the right way to get to a point, to how to negotiate his way there. I would have thought my grandfather was a tougher business man,” says Oppenheimer.

“I always knew that my father was there and I could discuss business matters with him, and that gave you a head start, it never got you to the finishing line, so that was whether you could deliver or not. He taught me business went on and it was an assessment of risk and to be a successful business man you have to take risks. There is no good being risk adverse, then you go nowhere.”

Nicky Oppenheimer’s air harks back to the gentility of 1950s Britain, where he began his education at prep school at the age of seven. Harrow and Christ Church Oxford followed.

“I am of an age where going to university was the last holiday of your life and I thought that was absolutely fantastic. Politics, philosophy and economics was a good sort of all-round degree. I thought it was fantastic, wonderful life. I didn’t work very hard I got a third-class degree at the end of it all. But I had a lot of fun,” he says.

When Oppenheimer arrived home in South Africa, the army called him for national service.

“The army had a terrible problem with me and that was that I had a degree, and so if you have a degree you did your basics and then became an officer. So, I became an officer and then they had no idea what to do with me. I had no skills that were of any use to them at all. I was sent to a great big parking lot just outside Pretoria and I signed my name every time a vehicle came in and I signed saying the vehicle had four tyres and two headlights. I always say that the army taught me how to sign my name very fast,” he smiles.

Then, Oppenheimer took his seat on the board, which he was to occupy for 37 years.

“It is what I saw myself doing; I had a particular love within the Anglo business, the diamond business. I was lucky enough to achieve what any diamond person’s primary ambition would be and that’s become chairman of De Beers. I’ve been extraordinarily lucky,” he says.

Not too soon after the De Beers exit in 2011, the family set up its investment arm Tana Africa Capital with the investment company E. Oppenheimer & Son and Temasek, a sovereign wealth fund from Singapore. The partners put up $150 million each and sources say the family is also ready to invest the billions from the De Beers deal. The investment company will look at agriculture and consumer businesses. It will also consider deals in media, healthcare and education up to $50 million.

“We are Africans and we would like to invest in Africa. So we are busy looking for things to do, we have some investments but we are constantly on the lookout,” says Oppenheimer.

Tana Africa Capital has already invested in Promasidor Group, a company founded in the Democratic Republic of Congo in 1979, that sells everything from powdered milk to tea in 30 African countries. Regina is Egypt’s second largest pasta manufacturer and owns the country’s only durum wheat flour mill. It has an expanding export business into Africa and the Middle East.

Oppenheimer has faith in African entrepreneurs.

“People are pretty entrepreneurial in Africa and growing so and that is very encouraging, a constraint in Africa is bureaucracy,” he says.

“The problem rests on the fact that, so many African economies are mineral based. The thing with minerals is that you can’t pick them up and take them anywhere and that allows government, wherever they are, to be bureaucratic, which is not business friendly, because a business can’t simply say I don’t like you I’m going to go somewhere else, you’ve got to deal with it. As a continent we’ve got to learn that you’ve got to be business friendly and find ways to create an environment for business to flourish and that means a bit of a mind change. The important thing is they (governments) have a huge role to play in controlling the environment. The less they have to do with the actual business, in my view, the better.”

I venture that, in the words of Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni it is easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than it is to keep government out of business.

“What one has to realize and what governments have to understand is, they are missing an opportunity. The penny will fall and then they must do much more than you talked about. They have to create the environment, they have to set the rules and regulations and tax rates but actually running of business is something short term that government is really bad at.”

And corruption?

“You have to stand up for what is right, corruption is an extremely insidious and dangerous thing and very difficult to eradicate once it starts… I often ask people once you’ve become a corrupt society, how do you stop being a corrupt society? And you don’t get very satisfactory answers. I think you have to demonstrate that you can be successful and contribute to society while being ethically sound, and it will be a long and slow process.”

More legislation, I venture.

“I always worry about legislation and what is does. When legislation comes forward, it is designed to catch the crooks. To my mind the crooks are always too clever to be caught. What is does is make honest people’s lives intolerable. So there has to be legislation but there has to be a drive to get people to believe in business ethics and doing the right thing.”

Then there is the struggling mining industry, which Oppenheimer spent more than half of his life working in. South Africa was shaken by a costly four-month strike in the platinum mines, followed by sapping and unprecedented power cuts. The Energy Intensive User Group that represents 32 of the country’s biggest energy consumers – including the smelters and mines – says 97% of its members are cutting back on capital projects because of a fear of power cuts.

“I think [mining] has a huge contribution to make. People talk about it like it’s a curse, which it certainly isn’t. Minerals have a future, if you’re blessed with minerals that’s a fantastically good start – you’ve got to use them. I think what happened in Botswana is a good example of a country that has taken its diamond revenues and put it to a good cause. You’ve got to find a way of encouraging mining, and mining is more long term than almost anything else. So you’ve got to create an environment where somebody is going to invest billions of dollars with a view that the first return will be seven to ten years away and the confidence to believe that the deal you have and environment you’re dealing in will still be there in seven to ten years. Then you will find people who will invest and companies and businesses will do… It is going to depend on the mining legislation, which is a bit up in the air at the moment. If you want to invest in a mine, you have to say ‘am I confident that the environment that the government creates for me will stand the seven to ten year test.’”

Oppenheimer concedes that the battered image of mining, in the land of his birth, has made foreign investors think twice.

“I think that people are looking at South Africa and waiting to see – that’s a bad situation. You want them not to be in wait mode, you want them to be in invest mode. The key thing in South Africa seems to be the creation of jobs. The government task I think should be to do everything in its power to create jobs so that the huge number of unemployed youth we have in the country can get jobs, get wages, fair proper wages and that needs to color every decision they make,”

says Oppenheimer.

As for the man himself, he is throwing himself into a number of philanthropic projects including the effort to save the endangered pangolin. Apparently, the long-tailed, scaly mammal is prone to electric security fences in the bush and is dying out.

If the pangolin survives and corruption dies, surely anything is possible in Africa.

Loading...